Footnotes to a forgotten war

reviews artist and journalist Joe Sacco's new graphic novel, which tells the story of the forgotten 1956 massacres in the towns of Rafah and Khan Younis.

THERE IS no one else who does quite what Joe Sacco does. Part artist and part investigative reporter, he has spent the past 20 years traveling to some of the world's most broken and abandoned places, producing extraordinary works of war reportage in comic book form.

His meticulously detailed black-and-white comic books combine a keen ability to tease out complex history with genuine compassion for the stories of ordinary people living their lives in a war zone, often with no hope of escape.

Sacco developed his unique blend of journalism and cartooning with the serialized comic Palestine, documenting life in the Occupied Territories in the early 1990s, and honed his craft through a series of comics about the Bosnian war, most notably, the superb book-length Safe Area Gorazde.

In retrospect, they look like studies for Footnotes in Gaza, an artistic and journalistic tour de force that explores two almost-forgotten massacres in the towns of Rafah and Khan Younis, in the southern Gaza Strip.

If nothing else, Footnotes in Gaza should be respected as a triumph of investigative reporting. Digging away at what he calls "footnotes to a sideshow of a forgotten war," Sacco brings to light the long-buried story of the massacre of 386 unarmed Palestinians by Israeli troops during the 1956 Suez Crisis--275 in Khan Younis and 111 in Rafah--the largest mass execution of Palestinians on Palestinian soil in history.

Under the pretext of searching for guerrilla fighters who had been conducting raids along Israel's borders, the Israeli army shot hundreds of Palestinian men of military age during its brief occupation of the Gaza Strip in November 1956.

In Khan Younis, many people were killed in their homes or lined up against the wall of a 14th century castle in the town's center and executed. In Rafah, there was a more drawn-out process in which the male population of the refugee camp was rounded up inside the grounds of a school and "screened" to identify suspected fighters. Most were released after enduring hours of detention and terror, some were arrested and taken to prisons inside Israel, and others, mostly randomly, were killed.

SACCO INTERVIEWED dozens of Palestinian and Israeli witnesses and survivors, piecing together incomplete and sometimes conflicting eyewitness accounts into a coherent narrative of the chilling events. By illustrating these memories throughout the book, he takes us back into the past with stunning immediacy and directness.

Sacco has developed a sophisticated visual language of perspective, angle and framing, which he uses unapologetically to create sympathy for the Palestinian victims of the massacre.

The Israeli soldiers doing the killing are often literally faceless, their expressions hidden behind hats and helmets. In the few cases where we do clearly see an Israeli soldier's face, he's often distinguished by an act of compassion, such as one man who refuses to shoot a teenage boy.

In a trick also employed by the makers of the film The Battle of Algiers, Sacco often positions the viewer behind lines of Israeli troops, so their backs are toward us. (One example can be seen in a preview of the book on the Mondoweiss blog.) Palestinians, on the other hand, face our gaze head-on. We see their faces, their fear and their humanity, and we're unable to look away.

Sacco has used flashbacks in previous comics to illustrate the stories of his interview subjects, but never has his control over the line between the present and the past been so masterful. The constant visual shuttling between 1956 and today--sometimes both are contained in the same panel--reinforces how present the past is in Palestine, and how the trauma of past violence lingers in individuals and communities long after the dead are buried.

"Palestinians never seem to have the luxury of digesting one tragedy before the next is upon them," Sacco writes in the book's introduction. One of his reoccurring frustrations while doing research is the tendency of older interviewees to mix up details from '48, '56, '67 and later. The injustices of the past are continually being ground up, mashed together and bulldozed over by fresh horrors.

Sacco visited Rafah during the peak of Israel's campaign of house demolitions along the border with Egypt, and was in Gaza when American peace activist Rachel Corrie was killed, crushed by an Israeli bulldozer as she tried to defend a Palestinian home from demolition. These events are documented in the book as well, reinforcing the idea that little has changed in 50 years.

Yet even this recent history is now dated. The six and a half years Sacco spent writing and drawing Footnotes have included Israel's withdrawal of settlements and ground troops from Gaza, Hamas' victory in the 2006 Palestinian elections, the crippling siege on Gaza and last winter's Operation Cast Lead.

"Events are continuous, one after another," an old man tells Sacco, explaining why he has difficulty recalling the events of '56. And indeed, the cumulative effect of the book is of layer after layer of trauma being heaped on generation after generation of a besieged population with little hope in sight.

Many of the younger Palestinians he talks to don't understand his fascination with '56. "Every day here is '56!" snaps one man, after showing Sacco the bullet holes left by Israeli snipers in the wall of his home.

FOR SACCO, the importance of these fairly obscure events in 1956 is twofold. On the most basic level, a piece of history--perhaps incidental in the "grand narrative," but unforgettable to the people who lived it--has been preserved. This particular footnote has not been dropped from history.

On a deeper level, Sacco sees this history as providing vital context to events taking place in Palestine today. Sacco believes that context is essential, and precisely what's lacking in most mainstream journalism.

"I don't think the American media establishment does a very good job of providing context," Sacco told Nora Barrows-Friedman in an interview broadcast January 18 on KPFA's Flashpoints radio show. "American journalists...are often pressured to just talk about what's going on today, and history is often the last thing you're going to throw into an article, because...generally that's the kind of thing that will get cut."

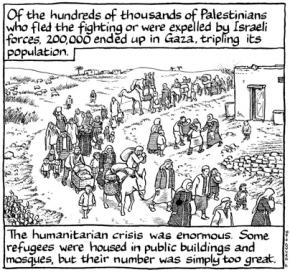

Footnotes in Gaza includes a fairly lengthy section depicting the Nakba--the expulsion of 750,000 Palestinians from the territory that is now Israel--and the years between 1948 and 1956, when Palestinian refugees lived in tents without clean water or adequate food, while their homes and fertile fields lay just over the border in what was now Israel. As Sacco told Barrows-Friedman:

It's essential to tell that. I wasn't going to drop the reader on November 3, 1956, and expect the reader to understand what was going on. Okay, you're going to see people getting killed, but what does it all mean? Why did it happen, or what was the context? Maybe the "why" can never really be answered on some level, but what was the context? Most of it took place in refugee camps. So, well, why are there Palestinian refugees? The reader needs to know that.

The massacres, and the grief and anger they generated, are a piece of Gaza's history to this day. In 2001, on assignment with Chris Hedges for Harper's magazine, Sacco interviewed senior Hamas leader Abdel Aziz Rantisi, who was 9 years old in 1956 and vividly remembered the death of his uncle in the massacre.

"I couldn't sleep for many months after that," Rantisi said. "It left a wound in my heart that can never heal. This sort of action can never be forgotten...[T]hey planted hatred in our hearts."

Sacco's work, at its best, teaches us the importance of remembering history in order to understand the present (and, hopefully, improve the future.) It also reminds us what power good journalism can have. In an interview with Palestinian freelance journalist Laila El-Haddad for Al-Jazeera English, Sacco responded to the charge that he is "biased" because his work clearly takes the side of the Palestinians:

I find it very difficult to be objective when to me there is a clear case of a people being oppressed. I'm not sure what objective means in a situation like that...

What's important to me is to tell the Palestinian viewpoint because it's not told well. Maybe we see Palestinian talking heads on TV. But what about the people on the street? What are they feeling? And its then you see their humor; you see their humanity; you see them being angry and you begin to understand why. And I think that sort of journalism does a service. That's what I'm trying to get across. I don't really think of it as biased, I think of it as being honest.