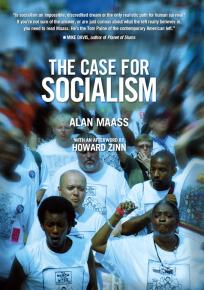

The case for socialism

Capitalism isn't working. Every day, every week, every month brings more evidence--hunger and poverty getting worse, jobs lost and homes in foreclosure, war and environmental destruction. And all the while, a tiny elite enjoys a life of unbelievable wealth and privilege. Something different is badly needed. But what is the alternative?

is editor of SocialistWorker.org and the author of a newly revised and updated edition of The Case for Socialism. Here, we publish an excerpt from the book.

WE LIVE in a world of shocking inequality.

Almost half the world's population--more than 3 billion people, the equivalent of the population of 10 United States--lives on less than $2.50 a day. A billion people are undernourished and go to bed hungry each night. Two in five people around the world lack access to clean water, and one in four lives without basic electricity.

Even in the United States, one in five children is born into poverty, and there's a better than even chance that we will spend at least one of our years between the ages of 25 and 75 below the poverty line.

But amid this crying need, there is immense wealth--fortunes beyond imagining for most people.

Just how immense? Think of it this way: Let's say we had a full year's wages for the average U.S. manufacturing worker--$37,107 at the end of 2008, according to the Labor Department--in stacks of $20 bills. If we laid all the bills end to end, they would stretch 928 feet. That's almost one-sixth of a mile--about three-quarters of a lap around a football field.

Now take Microsoft founder Bill Gates. According to Forbes magazine's survey of the richest Americans in 2009, he was worth $50 billion. If we had Gates's fortune in $20 bills, laid end to end, they would stretch for 236,742 miles. That's 1 million laps around a football field. Or six laps around the full circumference of the earth.

Bill Gates's fortune would stretch from the earth to the moon.

The ranks of the astronomically rich thinned a bit as a result of the financial crisis that began in 2007. But according to Forbes, the world's 793 billionaires as of 2009 still had a combined worth of $2.4 trillion. That's twice the combined gross domestic product of all the countries of sub-Saharan Africa, according to the World Bank--and more than the total annual income of the poorest half of the world's population.

Yes, you read that correctly. There are 793 people with more money than 3 billion people.

WHAT DOES this tiny elite do to have so much more than anyone else? The answer to this question is actually more infuriating.

Let's consider one of them: Stephen Schwarzman, Corporate America's best-paid chief executive in 2008 and number 50 on the Forbes 400 list of richest Americans the next year. In 2008, Schwarzman raked in $702 million as head of the Blackstone Group, a Wall Street investment firm--most in the form of stock awards from an arrangement struck before Blackstone became a publicly traded company the year before.

What does Blackstone do that it needs to reward its top executive so handsomely? Blackstone is one of the world's leaders in private equity investments, having helped pioneer the corporate takeover strategy. The idea is that an investment group swoops in and buys control of a company, takes out huge loans to finance the purchase, restructures operations to slash costs and free up cash, then resells the company and pays off the debt, while pocketing a big profit.

The basic principle is nothing more than buy low and sell high, but the key is in the borrowing, or what Wall Street calls leverage. If you can get control of a company by only putting down a fraction of its purchase price, then your rate of return on the original investment multiplies.

Blackstone has diversified into other areas. It dabbles in real estate and manages some hedge funds. But these other operations share something in common with Blackstone's main business.

They contribute nothing of any use to the economy or society.

Blackstone doesn't launch new businesses or develop innovative products. Its chief activity is to be a traveling parasite. It buys existing companies, sucks money out of them, and gets rid of them, preferably as fast as possible. Firms like Blackstone are the financial equivalent of the Bible's plagues of locusts, descending on areas, stripping them bare, and moving on.

The locust business has been good to Stephen Schwarzman. He lives in splendor in Manhattan in a 35-room triplex on Park Avenue, once owned by John D. Rockefeller, which he bought in May 2000 for $37 million. For weekends, depending on the season, he repairs to his mansion on eight acres in the Hamptons, or the 13,000-square-foot British colonial-style estate on a private spit of land in Palm Beach, Fla. There's also a beachfront mansion in Jamaica, but Schwarzman says he likes to leave that for his children to use.

"I love houses," Schwarzman once told a reporter. "I don't know why." Probably the 100,000 people estimated to be homeless on an average night in New York City would say the same. But they would know why.

When Schwarzman turned sixty in February 2007, he threw himself a birthday party. Not an ordinary party, of course, but one befitting a man of his grand accomplishments.

He rented the cavernous Park Avenue Armory and spent a reported $3 million transforming it into a giant-size replica of his Manhattan luxury apartment. Guests--among them, the governors of New Jersey and New York, foul real estate tycoon Donald Trump, and, naturally, dozens of Schwarzman's fellow Wall Street parasites--dined on lobster, filet mignon and Baked Alaska, and enjoyed (if such a thing is possible) a private concert by Rod Stewart.

On that one night, Schwarzman blew more money than 163 New York City families living at the poverty line--which is the fate of one in five residents of the city Stephen Schwarzman calls home--will see in a full year.

What could possibly justify this?

One man, whose life's work has been to manipulate the labor, property and wealth of others for his own gain, lives in a world of unimaginable privilege and power, where he can indulge any whim. And all around him is another world in which millions of people will work hard all their lives just to get by, and never accumulate a fraction of what he spends on a birthday party.

This twisted story is repeated throughout a capitalist society. The system that made Stephen Schwarzman a billionaire because of his skills as a financial parasite is the same system that protects his friends on Wall Street with a multi-trillion-dollar government bailout. The system that saves Wall Street from going under is the same system that devotes hundreds of billions of dollars every year to a military machine that goes to war for oil or whatever else serves the interests of the corporate elite.

Sometimes, discussions of wealth and finance can seem otherworldly--sums of money so large that it's hard to wrap your mind around them. But the consequences of capitalism are much more concrete.

The tens of millions that Stephen Schwarzman spent on another mansion in the Hamptons is money that thousands of workers didn't get paid because they were laid off after a corporate takeover engineered by Blackstone. The trillions that the U.S. government committed to the Wall Street banks is money that can't be used to expand food aid programs or to rebuild crumbling schools. The hundreds of billions devoted to the Pentagon every year is money that won't go to conquering AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa.

From the point of view of anyone who wants to do something to make the world a better place, this is money that has been stolen--pure and simple. A great portion of the immense wealth produced around the world is continually robbed to make the rich richer and the powerful more powerful still.

As John Steinbeck wrote in his novel of the depression years, The Grapes of Wrath: "There is a crime here that goes beyond denunciation. There is a sorrow here that weeping cannot symbolize. There is a failure here that topples all our success. The fertile earth, the straight tree rows, the sturdy trunks, and the ripe fruit. And children dying of pellagra must die because a profit cannot be taken from an orange."

The point of socialism, put simply, would be to stop the theft.

We mean real socialism. Not the hysterical caricatures of blowhards like Glenn Beck and others on the right. Socialism is also not the former USSR, or any of the remaining outposts of Stalinist totalitarianism, like North Korea or the corporate-friendly, sweatshop haven of China. Nor is it the center-left parties in European countries that call themselves socialist, but govern with pro-capitalist policies little different from their conservative counterparts.

Real socialism is based on a few straightforward principles. The world's vast resources should be used not to increase the riches of a few parasites, but to eradicate poverty and homelessness and every other form of scarcity forever. Rather than fighting wars that promote the power of the tiny class of rulers at the top, the working majority in society should cooperate in the project of creating a world of plenty. The important decisions shouldn't be left in the hands of people who are either rich or controlled by people who are rich, but should be made by everyone democratically.

Instead of a system that crushes our hopes and dreams, we should live in a world where we control our own lives.

CAPITALISM IS the source of poverty, war and a host of other evils. But it also produces something else: resistance.

For the last quarter of the 20th century, the theology of capitalism--with its worship of the free market and demonization of "big government"--reigned supreme in the U.S., through Republican and Democratic presidencies. But the economic and political crisis that began during the Bush years and accelerated into the Obama era has exposed the dark side of the system.

The man in Michael Moore's movie Capitalism: A Love Story who lost his Illinois farmhouse to foreclosure spoke for many people when he said: "There's got to be some kind of rebellion between people who've got nothing and people who've got it all."

Around the world, this sentiment has been the fuel of social explosions.

In Iceland, where the financial crisis became a political one in early 2009, masses of people, braving tear gas and riot police, besieged the world's oldest parliament building, drove the old political establishment from government, and installed a coalition of Left Greens and Social Democrats in power, with the first openly lesbian prime minister in the world at its head.

In Bolivia, insurrectionary demonstrations toppled the U.S.-backed government and opened the door to a new stage in the struggle. In Iran, the theft of the presidential election in 2009 sparked mass demonstrations. And these are just a few examples among many.

The U.S. hasn't seen revolts on this scale. But it wasn't quiet either. For example, for millions of people, enthusiasm for Barack Obama's victory in November 2008 was dampened by the success of Proposition 8 in California--a ballot measure that overturned equal marriage rights for same-sex couples.

But the passage of Prop 8 set off an explosion of protest, starting the night of the election itself, and building throughout the weeks and months that followed. Rather than react with demoralization, a new generation of activists for LGBT equality adopted the Obama campaign's message of "Yes we can"--itself appropriated from the immigrant rights movement slogan "Si se puede."

There are other sparks in the air. In California, severe budget cuts ignited a wave of demonstrations in defense of public education as the new school year started in 2009--with students, teachers, faculty and the community coming together to show opposition. Weeks after the 2008 election, the labor movement was electrified by the factory occupation at Republic Windows & Doors in Chicago, where workers not only succeeded in winning a severance package due to them after being laid off, but also kept their plant open.

Sit-ins in Senate committee hearing rooms against the sellout of genuine health care reform. Days of action to stop innocent men from being executed. Civil disobedience against coal companies fouling the Appalachians with mountaintop removal mining.

SUCH STRUGGLES are part of a rich history of opposition to inequality and injustice. And like those of the past, today's movements face a similar message from the powers that be, and also sometimes within their own ranks: Wait. Be patient. Don't be too radical. Be realistic.

Barney Frank seems to have appointed himself spokesperson for these voices in the Obama era.

Frank is the veteran congressman from Massachusetts, the first openly gay federal lawmaker, and one of the best-known fixtures of the liberal wing of the Democratic Party. Through the long reign of George W. Bush, he decried the policies of war, scapegoating, and more tax cuts for the already rich. And he spoke passionately about what was needed to end the tyranny of the Republican right: Put the Democrats back in power. Elect a Democratic majority in the houses of Congress. Put a Democrat in the White House.

By Election Day 2008, Frank had his wish. But his passion for change seemed to have cooled. At a 2009 commencement speech at American University in Washington, D.C., Frank advised graduates that "pragmatism," not "idealism," was called for these days. Forget about changing the world. "You will have to satisfy yourselves," he said, "with having made bad situations a little bit better."

It seems fair to ask, though, where "pragmatism" has gotten Barney Frank.

As the leading House Democrat shaping Wall Street financial bailout legislation, Frank "pragmatically" engineered the giveaway of hundreds of billions of taxpayer dollars to the banks, while ordinary people losing their homes have nowhere to turn. He "pragmatically" voted for funding the Obama administration's escalation of the war in Afghanistan. Frank "realistically" and "pragmatically" insisted that marriage equality, repeal of the military's "don't ask, don't tell" policy, and every promise that Barack Obama made to LGBT people during the presidential campaign would have to wait.

Ideals, Frank told the American University graduates, "never fed a hungry kid, they never cleaned up a polluted river, they never built a road that got people anywhere...Idealism without pragmatism is just a way to flatter your ego."

Actually, it's the other way around. It's not ideals that never fed a hungry kid. It's being pragmatic that steals the money that could be used to feed hungry children and gives it away to the banks. Pragmatism not only doesn't clean up a polluted river--it fills in the already polluted rivers with the debris of mountaintop mining.

There's an even more important point to be made here. Ideals--the hope that something can be different in society and the determination to act to make it different--are the first ingredient in every great social movement.

If you were Rosa Parks in Montgomery, Ala., in 1955, and you were ordered to give up your bus seat to a white man, the pragmatic thing to do would be to give it up, wouldn't it? Because realistically, what can one woman do to stop Jim Crow segregation?

But because people like Rosa Parks and thousands of others took action, unpragmatically and unrealistically, they changed history.

The commitment to act--to organize, to agitate and persuade, to petition, to protest, to picket--is the critical first step on the road to change. We live in a world today that badly needs changing, and what we do about it now matters.