Is socialism possible in the U.S.?

explains why the image of a classless, conflict-free society in the U.S.--the picture that dominates the media--was never a reality.

IN THE two decades after the Second World War, pundits and academics proclaimed the U.S. an exceptional society--one in which everyone was middle class and where concepts of class and class struggle were irrelevant.

Economic advancement, it was said, was possible for all. In an influential book, The End of Ideology, published in 1960, Daniel Bell celebrated a post-industrial society now free of class struggle. But the collapse of the postwar boom and the re-emergence of widespread unemployment and poverty in the 1970s and 1980s shattered this claim. Strikes, layoffs and union-busting put to rest the idea that class struggle was absent in the U.S.

Marx's statement in the Communist Manifesto--that "the history of all hitherto existing societies is the history of class struggle"--fits the history of U.S. workers much more accurately than the picture of the classless, conflict-free society.

From the formation of the first labor party in Philadelphia in 1827 to the great labor struggles of the 1930s and beyond, the class struggle of labor against capital has raged throughout U.S. history.

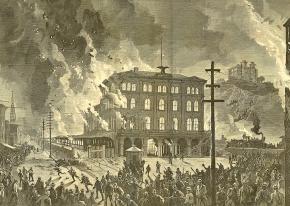

From the first virtually spontaneous mass national strike wave in 1877, when workers clashed in pitched batted with state militia men, national guardsmen and Pinkerton detectives, to the armed exchanges in the West Virginia mines between United Mine Workers miners and hired company thugs in the 1970s, workers have faced a ruling class willing to stop at nothing to protect its profits.

But Marx also argued that the development of the economic struggle of workers would inevitably lead them toward political consciousness and the corresponding development of political organization aiming at the conquest of power.

Whereas in countries like Russia and Germany, the development of working-class political organization developed more or less in conjunction with the development of the economic struggle, the same did not happen in the U.S.

It was not until the 1880s and the emergence of the Knights of Labor and the Socialist Labor Party that we begin to see the beginnings of a serious national class movement of workers. And it is not until the development of the Socialist and Communist Parties in the early to mid-20th century that masses of workers gravitate to socialist ideas.

However, the absence of a mass labor party in the U.S. today has led many to accept the argument that there are fundamental differences between the U.S. and other capitalist countries. And, from this, they conclude that work in the Democratic Party is the best that socialists can hope for. A look at the origins of the U.S. labor movement helps to put some of these arguments in perspective.

THE MOST popular argument is that prosperity has and always will defeat socialism, that socialism has been shipwrecked on "reefs of roast beef."

Add to this argument a list of what are considered permanent, sociological barriers to class-consciousness--class mobility, immigration and ethnic divisions, racism--and the case seems airtight.

There is no doubt that these and other factors contributed to the difficulties faced by the first Marxists in the U.S. Marx and Engels themselves referred to some of them.

Engels spoke in 1851 of "the ease with which the surplus population is drained off to the farms," arguing that access to land in the West would retard the development of class-consciousness.

And indeed, many of the early leaders of the working-class movement were drawn away from class politics by movements demanding free land in the West. It was not until access to western land was cut off by rapid expansion, Marx argued, that that the working-class movement would begin to focus exclusively on its conditions as a permanent, more or less settled class.

Marx and Engels also referred to the ethnic and racial divisions in the U.S. "Your great obstacle in America," Engels wrote in a letter to a German-American Marxist in 1892, "lies in the exceptional position of the native worker...[who] still takes up an aristocratic attitude...to the immigrants, of whom only a small section enter the aristocratic trade unions."

And he went on to argue that the immigrant population itself was divided into various nationalities: Jews, Italians, Bohemians, German and Irish, each of which the capitalists were adept at manipulating against one other.

The question of slavery was arguably one of the most decisive barriers to the development of an early socialist movement.

Marx argued that "labor in white skin cannot emancipate itself where in black it is branded," While the early labor movement in the 1830s tended to link abolition of slave labor with fighting the exploitation of free labor, the labor movement as a whole failed to develop a strong current of "labor abolitionism."

Alongside the New England Workingman's Association and many of the radical German workers organizations, which argued that "American slavery must be uprooted before the elevation sought by the laboring classes can be effected," stood "radicals" like George Evans who argued that labor should ally with the Southern slaveholders against Northern capital.

Whole sections of the working class, and in particular the Irish, responded to propaganda that in the event of abolition freed slaves would pour into the North and take their jobs.

It was only when the issue of slavery's expansion into the Western territories arose in the 1850s that the majority of trade unionists and labor reformers rallied to the banner of "free soil" and against slavery's expansion.

THE SITUATION was not helped by the anti-working class attitude of many of the leading abolitionists. William Lloyd Garrison in the first issue of The Liberator declared the trade unions "criminal" because they turned workers against their employers.

Even Wendell Phillips, who later became an advocate of workers' rights, argued in 1847 that workers had no need for unions because they were "neither wronged nor oppressed."

In the end, the labor movement failed to develop its own response to the slavery question. While organized workers formed the backbone of many a regiment in the Civil War, the working class remained subordinate to Northern capital, fighting more as "citizens" of a democratic republic than as workers fighting for a revolutionary transformation of society. The historic opportunity to link the struggle of slaves and wage workers was lost.

Another obstacle to the development of independent political organization of the working class was, paradoxically, the existence of (male) suffrage from the formative stages of the development of the American working class.

One of the issues that spurned the European working class to organize in countries such as Britain and Germany on a political basis was the absence of universal suffrage. In those countries, the working class had to wage protracted struggles for the franchise.

In the U.S., the young workers movement had no need for such a struggle. In addition, as Engels pointed our, the Constitution causes "every vote for any candidate not put up by one the two government parties to appear to be lost." This made the entrance of third parties into the political fray much more difficult.

Finally, America retained the strongest tradition of bourgeois democracy as a result of the struggle in 1776. Unlike the French revolution, where a plebian, "sans-culotte" radicalism arose from below of artisans, unemployed and journeymen which had to fight against both the old landed gentry and section of the French bourgeoisie who recoiled in horror from the revolution, the American Revolution remained from beginning to end firmly in the hands of the political representatives of the American bourgeoisie.

Whereas in France the revolution produced small strands of radical, communist and socialistic ideas, the American Revolution strengthened the politics of bourgeois democracy.

The ideas of democracy and individual rights continued to be nurtured by the existence of a large class of farmers which predominated in the U.S. until the latter part of the 19th century.

IN THE first period of Marxist organizing in he U.S., the working-class movement was still in its infancy. Its failures are, in the main, attributable to this. In the period prior to the Civil War, it was not strictly class struggle politics that prevailed. The primitive level of development of the working class mitigated against a unified national working-class movement.

Even the rhetoric of labor leaders was couched in terms of the rights of labor as citizens of the republic, and the struggle was not so much capital versus labor, as rich versus poor, "moneyed aristocracy" versus the "producers"--a term which often included small owners and master craftsmen who employed the labor of others, not to mention small farmers.

But all of this began to change rapidly around the time leading up to and after the Civil War, as the country embarked on a period of massive industrial expansion. From 1850 to the turn of the century, the population almost quadrupled and the wealth of the country increase by more than tenfold. Half of this wealth was controlled by 40,000 families.

By 1880, a majority of those in the working population were already wage workers. The Jacksonian dream of a democracy based on the "yeoman farmer" faded behind the smoke of burning coal and din of pounding steel.

Al the factors that inhibited the development of working-class organization in the U.S. were just that: inhibiting factors, rather than insurmountable obstacles. Many of the factors listed as decisive were historically limited.

The "land drain" argument became invalid by the late 19th century, as the West rapidly became populated. The argument about prosperity was invalidated as waves of cheap labor poured into the country throughout the late 19th and early 20th century, driving down the wages of the vast majority of workers to intolerable levels.

The first truly national working-class rebellion--the revolt of 1877--signaled the emergence of the American working class as a forced to be reckoned with. From this point on, modern working-class history begins in the U.S.

And while a whole host of problems remained in the path of workers' political development--most importantly racism--what is striking is the recurring periods in which workers in the U.S. have over come these obstacles.

The growth of a mass Communist Party in the 1930s belies the notion of "American exceptionalism." The problem is that the Communist Party sought accommodation with the Democrats instead of building an independent class-wide movement.

McCarthyism and the 20 years of boom made such a development impossible in the past generation. But these specific historical factors are not permanent features of U.S. society. Given a new period of working-class struggle, the U.S. working class can be won to socialist ideas.

This article originally appeared in Socialist Worker in February 1989.