The legacy of Haymarket

chronicles the hidden history of the Haymarket Martyrs, the movement for the eight-hour day and the origins of May Day.

MAY DAY was first declared a workers' holiday by the first conference of the Second International socialist movement to commemorate the struggle for the eight-hour day in the U.S.

The year 1886 began with a number of victories for the labor movement, but ended in May with a series of bitter defeats and the eventual execution of four of the movement's most dedicated leaders, who came to be known as the "Haymarket Martyrs."

The eight-hour movement of 1886 was set in motion--ironically--by the leadership of a craft union, the Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions, the predecessor to the conservative American Federation of Labor. The Federation passed a resolution at its Chicago convention in 1884 that declared that "eight hours shall constitute a legal days' labor from and after May 1, 1886."

The Federation advised its members to take strike action if necessary to secure this demand.

At the time, the average working day ranged from 14 to 18 hours. Attempts at legislative reform had proven fruitless. It was clear that, unless workers were willing to strike to win it, the eight-hour day wouldn't come to be.

The Federation's calls to strike were met with ridicule from newspapers across the country, which predicted the movement was destined to be stillborn.

Moreover, the leadership of the then-flourishing Knights of Labor, Terrence Powderly, also opposed the idea of striking for the eight-hour day. He stated, "No assembly of the Knights of Labor must strike for the eight-hour system on May 1st under the impression that they are obeying orders from headquarters, for such an order was not, and will not, be given."

Powderly proposed that instead of striking, each Knights of Labor assembly should "have its members write short essays on the eight-hour question."

But opposition to he eight-hour movement fell on deaf ears, as workers took up the banner for an eight-hour workday and began going on strike to win it in the early apart of 1886. To Powderly's dismay, local assemblies of the Knights of Labor not only took part in the strike wave, but initiated much of the activity. In turn, the Knights of Labor continued its rapid growth, its membership increasing to nearly 703,000, most of them unskilled workers, by July 1886.

ON MAY 1 and in the days following, at least 190,000 workers went on strike for the eight-hour workday across the country. An additional 150,000 won the demand just by threatening to strike.

For example, 4,000 New York City furniture workers won a shorter workday simply by reporting to work at 8 a.m. and leaving at 5 p.m. The total number of workers involved in the movement was 340,000. And 65,000 of the striking workers were from Chicago.

Not only was the eight-hour campaign among the strongest in Chicago, but it was also a political center for the left wing of the labor movement--thanks to its dedicated and capable leadership.

As leading members of the anarchist International Working People's Association (IWPA), individuals such as August Spies and Albert Parsons--whose politics were strongly influenced by a revolutionary syndicalist tradition, were able to win over the IWPA, also known as the Black International, toward working inside the trade union movement.

Parsons and Spies, along with Lucy Parsons, Samuel Fielden and Michael Schwab, built a following among activists workers--many of whom were German immigrants--in Chicago, so that their city alone accounted for more than one-third of he Black International's 5,000 to 6,000 members,

But the employers weren't long in organizing a counter-offensive against the workers' movement. The Western Boot and Shoe Manufacturers Association, representing 220 local businesses, was formed to try to crush the strike movement.

They enjoyed the full cooperation of the local police. Armed police began breaking up meetings of workers on Monday, May 3. By that afternoon, a group of 200 police attacked a group of strikers at the McCormick Reaper Works as they picketed scabs leaving he works. Armed with clubs and guns, the police chased the workers as they tried to run away, firing at their backs.

Four workers were killed and many others injured by the senseless violence of the police.

Strike leaders met and decided to call a street meeting of workers the following evening to protest against the violence. The attacks continued into the following day, as police broke up gatherings of workers by force.

Some 3,000 workers attended the street meeting, held in Haymarket Square, and heard the speeches of Parsons and Fielden, who spoke to the strikers from a wagon. The crowd was very subdued, and when it began to rain, many people left--including Parsons and Spies. Fielden continued speaking to the few hundred who remained.

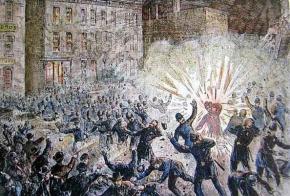

Shortly after 10 p.m., 176 armed police marched in and commanded the workers to disperse. Fielden cried out that the meeting was peaceable. Just as the police captain turned to give an order to his men, a bomb was thrown into the police from just south of the speakers' wagon. It exploded in the midst of the police, injuring dozens of police and eventually killing seven.

The police reaction was immediate: they opened fire directly into the crowd at short range, killing several workers and injuring 200. After the scene, the neighborhood was thrown into chaos, as the wounded were dragged into local drug stores, and the police went on a rampage of terror against union activists.

It was never formally discovered who actually threw the bomb--it could have been an individual worker, angered by police violence, or it could have been a police provocateur. But one thing was clear: none of those arrested, tried or convicted had anything to do with the crime. Many of them were not even present when the incident occurred.

THE POLICE and the government used the Haymarket incident as an excuse to crack down on the entire labor movement in a reign of terror that lasted for days in Chicago: workers' homes were raided, as activists were dragged from their beds and arrested.

Meeting halls and offices were broken into. Anyone with any connection to the labor or the socialist movements could be held. Each day, police "discovered" ammunition, rifles, pistols, materials for making bombs and anarchist literature.

All in all, 31 workers were finally indicted for murder, conspiracy and other charges. Eventually, the number was whittled down to eight--all of whom were key leaders of the Chicago working-class movement. The accused included Parsons, Spies, Schwab and Fielden, as well as Adolph Fischer, George Engel, Oscar Neebe and 21-year-old Louis Lingg.

The newspapers did their best to aid the police in creating an atmosphere of lynch-mob hysteria. Newspaper headlines shrieked "Red Ruffians," "Bomb Slingers," "Dynanarchists" and "Bomb Makers" to describe the eight accused men.

It was soon made explicit that the eight were on trial for their political beliefs, not their actions on the evening of May 4. The prosecutor, Julius Grinnell, stated this quite plainly in his summation statement at the trial's end:

Anarchism is on trial. These men have been selected, picked out...and indicted because they were leaders. There are no more guilty than the thousands who follow them. Convict these men, make examples of them, hang them and you save our institutions, our society.

The jury--which included a relative of one of the bomb victims--did just as Grinnell suggested. They convicted all of the defendants, sentencing all by Neebe to death.

Neither attempts at appeal through higher courts nor pressure from the labor movement succeeded in reversing the death sentence for the men. Under the intense pressure, the governor at last commuted Fielden's and Schwab's sentences to life imprisonment.

The day before the scheduled execution, 21-year-old Lingg exploded a tube of dynamite inside is mouth, an act of suicide. Finally, on November 11, 1887, the four remaining men--Spies, Fischer, Engel and Parsons--were hanged. Spies' last words were: "There will be a time when our silence will be more powerful than the voices you strangle today."

Some 25,000 workers marched in the funeral for the hanged men. But for the time being, the struggle for the eight-hour day had been lost.

FOLLOWING THE Haymarket incident, police--using the alleged "anarchist plot" as an excuse--attacked gatherings of strikers even more brutally than before. Within a week after May 1, strikers began to return to work. By May 22, only 80,000 out of the original 190,000 strikers remained on the picket line.

As soon as the movement began to weaken, the employers began to retract the eight-hour day reforms that had been won. Bradstreet's reported on January 8, 1887, "the grand total of those retaining the concession will not exceed, if it equals, 15,000."

The labor movement as a whole--and the anarchist and socialist movements in particular--suffered a terrible setback in the years that followed. Even when Gov. John Altgeld officially pardoned the Haymarket Martyrs in 1893, and uncovered the government's elaborate conspiracy that had convicted the eight anarchists, the press refused to acknowledge the men's innocence.

To this day, the Haymarket Martyrs, victims of one of the worse government frame-ups in U.S. history, have yet to be exonerated by the press or the official history books. The events of May 1886 are simply ignored.

It is up to the working-class movement to keep the memories of these men alive, to learn the bitter lessons of their struggle, so that they will not have died in vain.

For as August Spies predicted on the day of sentencing:

If you think that by hanging us, you can stamp out the labor movement...the movement from which the downtrodden millions, the millions who toil in want and misery expect salvation--if this is your opinion, then hang us! Here you will tread upon a spark, but there and there, behind you and in front of you, and everywhere, flames blaze up. It is a subterranean fire. You cannot put it out.

This article originally appeared in Socialist Worker in May 1989.