Labor during the Second World War

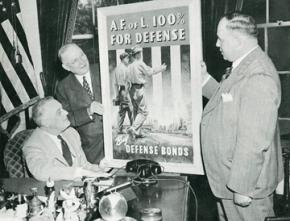

The massive demand for labor created by wartime production created favorable conditions for workers to make gains. But, as shows, union leaders agreed to a series of crippling concessions to prove their zeal for the war effort.

BEFORE THE outbreak of the Second World War, the leadership of the two major trade union organizations, the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), had already show an interest in curbing rank-and-file militancy.

They tried to channel sit-down fever into more stable forms of collective bargaining.

For trade union leaders like Sidney Hillman of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers and Philip Murray of the Steelworkers, the outbreak of war in 1941 provided an opportunity to increase their influence in the corridors of power through their ability to control the union ranks.

Roosevelt proved able to draw the top union brass into cooperation with the government war effort. They agreed to a "no-strike pledge" in 1941. After U.S. entry into the war in early 1942, they voluntarily gave up (without any consultation with the rank and file) workers' right to receive time-and-a-half for Saturday work and double time for Sundays.

The majority of union leaders supported Roosevelt's demand that worker comply with a freeze on wages on the completely hollow promise that prices in general would be controlled. In reality, rampant price gouging and wartime profiteering produced severe cuts in workers' living standards.

Union leaders also participated in Roosevelt's War Labor Board (WLB), a tripartite institution composed of representatives of business, labor and the government that ruled consistently in favor of business and against labor.

It was described by one conservative AFL official as "a policeman's stick," whose aim was disciplining labor to ensure the smooth running for the war machine.

In a number of cases, union leaders supported government military action to break strikes.

So for example both Murray and Hillman approved Roosevelt's initiative in June 1941 to send troops to occupy the North American Aviation plant in Inglewood, Calif., and its threats to draft strikers into the army.

A few years into the war, when the miners began to defy the no-strike pledge, Congress passed the Smith-Connally Act in 1943 over Roosevelt's veto. The bill authorized the War Labor Board to punish through fines and imprisonment any persons who organized slowdowns or strikes in government-seized plants.

The bill authorized government seizure of plants to break strikes and the now-infamous 30-day "cooling-off" period. Even though Roosevelt has made it clear that he opposed the act because it wasn't tough enough, Murray and William Green thanked Roosevelt for his veto and wrote notes to him pledging their commitment to maintaining the no-strike pledge.

SIDNEY HILLMAN went the farthest in his collaboration with Roosevelt, running the Office for Production Management (OPM) during the war together with the General Motors magnate William Knudsen.

Roosevelt rewarded Hillman in January 1942 by scrapping the OPM and unceremoniously refusing to re-appoint Hillman to the newly created War Production Board.

The unions got very little for their concessions, and what they did get was beneficial to the bureaucracy more than the rank and file. The dues check-off system, whereby the employer deducted union dues directly from the payroll, ensured a steady income for the union leadership, but alienated workers by making the employer the union treasurer.

In return for its acceptance of the wage freeze, the WLB granted unions "maintenance of membership" clauses that merely stipulated that workers must remain union members for the life of a contract--a far cry from the union shop, which required all workers to join the union in a union company.

For the employers, "maintenance of membership" was the union leadership's reward for policing the membership, enforcing the no-strike pledge, the wage freeze and speedup.

The war brought massive profits for big business. In 1943, major corporations doubled their profits over 1940. Massive profits were to be made by the big companies like GM and U.S. Steel, which made millions producing shoddy military goods at bloated prices.

Nine of 15 shipbuilding companies, for example, (investigated in a wartime U.S. Senate hearing) received above-taxes guaranteed net profits from government contracts in 1941 that exceeded the worth of their entire properties in 1939.

These companies produced "Liberty" ships that cracked in half at sea and cost the lives of thousand of sailors.

For workers, the war brought speedups, longer hours and drastic cuts in living standards. Piecework was reintroduced--labeled as "incentive pay"--which led to drastic increases in hourly output.

One survey of 1,000 plants that used "incentive pay" showed an average increase of 40 percent in output for pay increases of 15 to 20 percent.

But inflation nullified even these increases. Union participation in a presidential committee on the cost of living concluded that between January 1941 and January 1944, the cost of living increased by 43.5 percent.

WORSENING LABOR conditions led to simmering discontent. In spite of the no-strike pledge, concerted efforts of the union leadership to prevent strikes and the jingoistic media onslaught that faced workers who struck, thousands of strikes broke out during the war.

Although isolated and less likely to succeeded than in the prewar period, strikes were far more numerous in the four years during the war than in 1936-1939.

The miners, behind their President John L. Lewis--one of the few top leaders to defy the no-strike pledge and condemn the wage constraints--were the first to fight.

The conditions for miners were particularly bad. The "Little Steel formula" of the WLB by which they determined wage settlements effectively allowed for no wage increases for miners, who were already among the lowest paid production workers.

Yet food costs between 1939 and 1943 had gone up in mining towns by almost 125 percent. Moreover, the rate of mining accident deaths--64,0000 in 1941, 75,000 in 1942 and 100,000 in 1943--exceeded the death rate in the army during the war.

In response to mass pressure from the ranks for action, Lewis led a series of disciplined strikes against Roosevelt and the coal bosses.

In spite of massive government mobilization against the strikes and the opposition to the strikes of AFL and CIO leaders who feared the strike fever would spread and jeopardize their relations with Roosevelt, the United Mine Workers (UMW) was able to wrest concessions from the operators.

Lewis, to be sure, was as much of a maneuverer as his rivals in the CIO (the UMW split from the CIO in 1942). In the UMW, he ruled autocratically, brooking no opposition to his control. What made him different from the Murrays and Hillmans was his willingness to direct the mood of discontent among the rank and file.

The miners' success emboldened other workers to fight the no-strike pledge.

Dozens of resolutions were passed by rank-and-file delegates in support of the miners over heads of the union leaders, and more strikes began to break out in auto and steel. These were quelled only by disciplinary action from both union leaders and the government.

Union leaders used firings and expulsions frequently to discipline striking members. So for example, President Sherman Dalrymple of the United Rubber Workers ordered in January 1944 the expulsion of 72 members of General Tire and Rubber Company Local 9 for participation in a strike.

Such actions often provoked action from the rank and file in their defense. When the 72 workers were dismissed from their jobs, workers organized a rehiring campaign and mobilized in Dalrymple's home local a successful vote for this expulsion from the union, which was only later reversed through bureaucratic maneuvering.

In auto, which experienced a record number of strikes in 1944, workers began to organize around defiance of the no-strike pledge. Striking workers from Ford Local 400 in Highland Park, Mich., jeered UAW's Ford division director when he tried to organize a back-to-work movement.

On the picket line, Local 400 workers wore T-shirts saying, "Scrap the no-strike pledge."

Rank-and-file organization around this slogan produced substantial minority votes at a number of union delegate conferences around the country in spite of intense efforts by the trade union leadership to prevent discussion on the issue.

THROUGHOUT THE 1930s, the Communist Party (CP), despite its subservience to Stalin, was able, through its untiring work in the trade unions and among Black, to grow into the foremost political workers' organization in the U.S.

The war brought home forcefully the drastic consequences of its subordination to Russia's war aims.

During the period of the Hitler-Stalin pact, August 1939 to June 1941, the CP was fiercely critical of U.S. imperialism and of Roosevelt. With Hitler's eastern invasion, the CP became the single-most outspoken supporter of Roosevelt's war drive.

Within the labor movement, this meant that CP union leaders were the most tireless advocates of speedups, piecework and the no-strike pledge.

Leading communist William Z. Foster called upon workers to "take the lead in accepting willingly every sacrifice necessary to prosecute the war."

On May 25, 1944, CP sympathizer Harry Bridges, head of the CIO's International Longshoremen's and Warehousemen's Union, motivated a resolution at a Local 6 meeting in San Francisco by stating that strikes were "treason" and that the government should "refuse to give consideration to the demands of any section of labor" that went on strike.

He argued that the no-strike policy should be maintained "indefinitely" after the war's end.

Communist Party leaders ordered their members to scab on strikes, fingered militants to the government and employers and even organized physical assaults on workers who defied Roosevelt.

The Communists' policy during the war so impressed some employers that they preferred communist-led unions over anti-communist unions. But for rank-and-file militants, the CP's policies served to discredit them.

Their commitment to support for Roosevelt meant that they were also the most vocal opponents of a labor party--at a time when many workers were beginning to see the need for politics independent of the Republicans and Democrats.

In short, the CP, instead of providing a real alternative to the trade union bureaucracy and Roosevelt, served to tie the aspirations of the thousands of militants to the Democratic Party and away from militant economic and political action.

Their despicable behavior made them easier targets in the post-war anticommunist witch-hunts that drove them from the labor movement.

Not even the outbreak of war was able to completely halt the struggles of U.S. workers that had burst forth so violently in the 1930s. In the postwar period, the simmering discontent of the war years was to burst forth into the largest strike wave in U.S. labor history.

This article originally appeared in the in August 1990 issue of Socialist Worker.