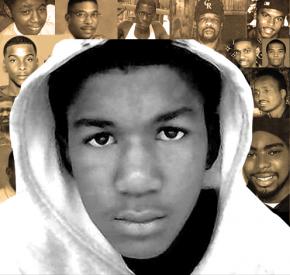

The many other Trayvons

The U.S. has a long history of violence against African Americans, committed by racists and police--but as explains, there is also a history of resistance.

POLICE AND racist killings of African Americans are horrifyingly familiar. So why the protest movement around the case of Trayvon Martin--and why now?

Rev. Jesse Jackson, speaking at a March 30 press conference with Black family members of young people recently shot and killed by police in the Chicago area, put his finger on the issue. The mainstream media "has adjusted" to the routine deaths of African Americans at the hands of cops--but their family members haven't.

"The traditional media did not break this story," Jackson said. "It was Facebook and Twitter that really broke the story. Here, when young brother Watts is killed, it's a one-night story, and we move on and wait for the next one."

Jackson was referring to the police murder of Stephon Watts, the young Black man with autism shot by police in Calumet City outside Chicago in February. Stephon's father, Steven Watts, also spoke:

My son has autism, and he just wanted to get out of the house. He saw the police. He's afraid of the police, and he just wanted to get past them. He had a butter knife in his hand, and just because he had a butter knife in his hand, the officers came to the conclusion that it was okay to use deadly force.

They shot him once. He fell. He tried to get up, and they shot him again. They did not try to wound him. They did not try to shoot him in his arms or legs. They did not try to hold him or Taser him. They shot him in the torso. They meant to kill my son. And now he's gone, and I have no answers.

I feel compassion for Trayvon. I really do. But what about my son? I feel pain and anger inside of me. I see my son getting shot every night before I go to sleep. I see the same thing over and over. I see smoke coming out of the gun. That's how close I was.

Also at the press conference was Angela Helton, mother of Rekia Boyd, killed by an off-duty Chicago police officer who opened fire at an unarmed young Black man in Chicago's Douglas Park neighborhood.

Helton was shocked at the killing of Trayvon, but angry that the death of her daughter barely made the nightly news in Chicago. "My daughter was murdered for no reason at all," she said. "I just want justice for my daughter, and I want the person who murdered her prosecuted to the fullest extent."

Trayvon Martin, Stephon Watts and Rekia Boyd have joined the uncounted numbers of African Americans murdered by racists or law enforcement in the nearly 150 years since the end of the Civil War.

A century ago, such killings were commonplace in the South--lynchings aimed at terrorizing a Black population denied basic and political rights under the Jim Crow system, America's version of apartheid. These days, the majority of such racist killings are carried out by police--sometimes even African American ones--as part of a system of social control that author and activist Michelle Alexander calls "the new Jim Crow."

MY NEARLY 30 years as a reporter for Socialist Worker spans much of the "law and order" era that today has put more African American men in prison than were enslaved in 1850. Over the years, I've witnessed the agony of the parents and family members of African Americans killed not only by police, but by racists who took their cue from the cops and pulled the trigger themselves.

In October 1984, a few weeks after I moved to New York City, police officer Stephen Sullivan shot and killed Eleanor Bumpurs, a 66-year-old African American grandmother, in her apartment after she allegedly brandished a kitchen knife. Somehow, Sullivan and the other five cops on the scene couldn't manage to subdue Bumpurs without firing two shotgun blasts into her.

And if the murder of Bumpurs wasn't shocking enough, there was the demonstration of 10,000 NYPD officers--the force numbered 25,000 at the time--in support of Sullivan when he was indicted for second-degree manslaughter. A judge ultimately acquitted Sullivan of all wrongdoing in a nonjury trial.

Racist vigilante justice is nothing new, either. The police coddling of George Zimmerman and support for him in the conservative press reminded me of the media embrace of Bernhard Goetz, the New York City "subway vigilante," who in December 1984 shot four African American youths after they asked him for $5.

When a wounded 19-year-old Darrell Cabey tried to get away, Goetz followed him. "You don't look so bad, here's another," Goetz said as he shot Cabey in the side at point-blank range. In Goetz's statement to the police, he justified his action by describing the young men as "savages" and said he was prepared to "murder" them.

Goetz ultimately did just eight months in prison for unlawful possession of a firearm--but was acquitted of attempted murder. Meanwhile, Cabey's injury put him in a coma that left him brain damaged, with the mental capacity of a third grader. Cabey's mother won a $43 million lawsuit against Goetz, but was unable to collect.

Of course, police account for far more shootings and murders of unarmed African Americans than vigilantes like Goetz. Meeting Rekia Boyd's mother in Chicago brought back memories of Veronica Perry, the mother of Edmund Perry, a 17-year-old Phillips Exeter Academy graduate who was bound for Stanford University when he was shot and killed by a New York City police officer in upper Manhattan in 1985.

The cop who shot him, Lee Van Houten, claimed that Perry and another African American youth had tried to mug him. But Perry's body had no cuts, bruises or powder burns indicative of a struggle--just like there was no evidence that Trayvon Martin attacked George Zimmerman.

Like the Martin murder, the police tended to the killer, not the victim. As I wrote then: "Why did Van Houten's fellow cops take him to St. Luke's Hospital for cuts and bruises and leave Perry bleeding on the sidewalk, just 100 yards from the hospital door?" Veronica Perry, died just six years later at the age of 44, reportedly as a result of a heart condition.

The anguish of Steven Watts, the father of Stephon Watts in Chicago, reminded me of the horror on the face of Jean Griffith Sandiford, the mother of 23-year-old Michael Griffith, who was chased by white racists onto a Queens highway, where he was struck by a car and killed in 1986.

Griffith's car had broken down near Howard Beach, a white neighborhood where he and his friends walked to try to get help. They found a lynch mob instead. The NYPD's 106th Precinct--which months earlier had been exposed for torturing Black prisoners with electric cattle prods--failed to respond to three emergency calls about the attack on Griffith and two companions.

It took a series of protests in Howard Beach to force Gov. Mario Cuomo to appoint a special prosecutor to investigate the murders.

It was racists again who took the life of 16-year-old Yusef Hawkins for daring to visit another white neighborhood, Bensonhurst in Brooklyn, to buy a car in 1989.

I'll never forget the hatred and threats hurled at those of us in the multiracial weekly marches in Bensonhurst--or the courage of the African Americans who led that struggle to bring Yusef's killers to justice. Rev. Al Sharpton, who usually headed the weekly marches, was stabbed in the chest while preparing for one Saturday protest.

THE RACIST police shootings in New York City from the 1980s on--including, more recently, Amadou Diallo in 1999 and Sean Bell in 2006--stand out for their brazenness. Even the mainstream media had a hard time ignoring the fact that police fired 41 bullets at Diallo and fired 50 rounds at Bell.

Yet the fact is that police carry out racial profiling of Blacks and Latinos in every city in the U.S.--and that members of these groups are vastly more likely to end up dead in encounters with police than whites.

That's certainly the case in Chicago, where I moved in 1997. In June 1999, Robert Russ and LaTonya Haggerty--two young African Americans, both unarmed--were killed in separate police shootings within a 24-hour period.

Those killings highlighted the role of police as the primary enforcers of institutional racism--the cops who fired the shots that killed Russ and Haggerty are themselves African Americans. It's the social function of police--not simply the racial identity of individual cops--that leads them to regard all Blacks, especially young Black men, as dangerous suspects, whether they are armed or not.

But it's the white cops who cultivate a culture of racism and a code of silence that allows police to kill African Americans with impunity. In my hometown of Cincinnati, the police brass and Fraternal Order of Police were for decades dominated by men from the historically white west side of town, where I grew up.

A series of police killings and beatings of unarmed African Americans over several years finally boiled over in April 2001, when a white cop killed 19-year-old Timothy Thomas in a downtown alley in a neighborhood targeted for gentrification. When several hundred African Americans protested at City Hall, the police attacked them, sparking several days of riots. As I wrote about the police crackdown that followed:

For Cincinnati cops, every African American was a target. One 53-year-old Black man was shot by beanbags 10 times--for simply walking down the street in daylight. Another woman's scalp was partially torn off by one of the projectiles. Hundreds of people--almost exclusively Black, many of them homeless--were arrested by the cops for curfew violations.

I arrived in town amid the curfew and watched police in military gear swarming through African American neighborhoods, peering down riflescopes and kicking in doorways. I could witness this firsthand because my white skin gave me a passport onto streets that were off-limits to anyone Black.

A major riot in sleepy and conservative Cincinnati got national attention, as worried politicians and pundits weighed the implications of such a rebellion. It was one thing for Los Angeles to erupt in 1992 following the acquittal of the cops who beat Black motorist Rodney King, and were caught on videotape doing it. But if Cincinnati could explode over racist police killings, it could happen anywhere.

A DECADE later, it's the murder of Trayvon Martin that has once again put a spotlight on the reality of racist murder in the U.S. While the police didn't pull the trigger this time, they certainly conspired with George Zimmerman to promote his claim that he killed Trayvon in self-defense.

Tellingly, both protesters and the media have put the murder of Trayvon in the context of racist police violence nationally, rather than dismiss it as the isolated act of a white vigilante. Every day that Zimmerman walks free highlights the racist character of the criminal justice system. Everyone understands that if the shooter in the Sanford case were Black and the victim white, arrest and prosecution would have followed immediately.

As Jesse Jackson pointed out, it was grassroots activism that made the murder of Trayvon Martin national news and sparked a movement to demand justice. And the outrage over Trayvon is amplified by the growing discontent over the mass incarceration of African American men, which author Michelle Alexander has described as a new racial caste system.

After all, even African American men who survive their encounter with law enforcement find themselves facing trumped-up charges--and are compelled to plea bargain in order to limit time in prison, resulting in felony convictions that often strip them of voting rights and severely limit their employment prospects.

Another factor sparking activism around Trayvon is the Occupy movement, which put grassroots protest onto the political map and won the sympathy of millions of people fed up with rising inequality and corporate-dominated politics. Crucially, the massive outpouring of support for Trayvon has brought the question of racial justice to the fore for a new generation of activists who themselves got a taste of police repression when cops cracked heads to clear Occupy encampments last fall.

The challenge now is to give the movement against racist and police killings some local focus and staying power. Whether or not George Zimmerman is arrested, prosecuted and convicted, in every city, racist police brutality should become a focal point for activism. Speak-outs and panel discussions featuring those targeted by police--or their surviving family members--can be a starting point for campaigns against racial profiling and police harassment of people of color.

It's the duty of activists to cast a spotlight on the bitter experiences of African American and Latino youth at the hands of police and racists--because if they don't, no one else will. Since the great African American journalist Ida B. Wells undertook dangerous journeys to the South a century ago to document lynching, it's always been the Black, socialist and radical press that has taken the lead in exposing racist violence.

The racist murder of Trayvon Martin is, as many have pointed out, our contemporary version of lynching. Wells' words from her 1895 pamphlet, The Red Record, still ring true:

In slave times the Negro was kept subservient and submissive by the frequency and severity of the scourging, but with freedom, a new system of intimidation came into vogue; the Negro was not only whipped and scourged; he was killed.

The groundswell of protest demanding justice for Trayvon shows that, once again, people are prepared to take up Wells' legacy of fighting to put an end to these racist atrocities.