Poetry to make the world anew

pays tribute to a poet who gave voice to both anger and hope.

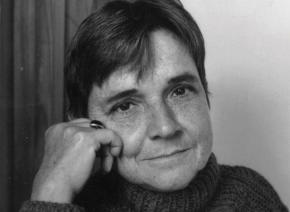

THE WOMEN'S liberation movement lost one of its most powerful and enduring voices last month with the death of Adrienne Rich.

Most famous as a poet who gave literary expression to the feminist movement of which she was part, Rich was also a radical, a political theorist and a lifelong activist. She dedicated her life and her art to the fight for social justice, and against war, oppression and inequality in all its forms.

With over 30 volumes of poetry and prose over six decades, Rich is one of the most prolific, memorable and important writers of the American left--one who has inspired activists for more than half a century, and who has left a rich legacy that will continue to inspire generations to come.

Born in Baltimore in 1929, Adrienne Rich was encouraged to develop her writing talent from an early age. At Radcliffe College, from which she graduated in 1951, her work received high praise from W.H. Auden, and her first collection was well received by critics. In 1953, she married Alfred Haskell Conrad, a Harvard economist with whom she had three children by the time she was 30.

Rich was already a successful poet before the women's liberation movement emerged onto the center stage of American culture and politics. She was a master of poetic form, who would undoubtedly have been successful with or without the feminist movement. But it was the birth of the movement that gave force and vibrancy to the formal ingenuity and aesthetic brilliance of her verse.

Her early poetry already smoldered with the repressed anger and potential of women trapped beneath the 1950s ideal of the suburban housewife. One of her more famous early poems, "Aunt Jennifer's Tigers," written in 1951, is a stunning testament to the way in which woman's oppression in the nuclear family stultified her creative potential:

The massive weight of Uncle's wedding band

Sits heavily upon Aunt Jennifer's hand.When Aunt is dead, her terrified hands will lie

Still ringed with ordeals she was mastered by.

The tigers in the panel that she made

Will go on prancing, proud and unafraid.

WHILE HER early poems earned her some success, it was the 1963 publication of Snapshots of a Daughter-in-Law that signaled Rich's entry into the political radicalization of the 1960s. Published the same year as Betty Friedan's The Feminine Mystique and Sylvia Plath's The Bell Jar, it became part of an incipient feminist literary canon that challenged every aspect of the 1950s Leave-It-to-Beaver vision of the happy housewife.

It also marked the beginning of new formal experimentation in her poetry, as Rich broke with the more distant voice and traditional poetic forms of her earlier work.

The next decade saw an explosion of poetry imbued with a sense of political urgency. While it was clearly the women's liberation movement that gave Rich much of her inspiration, the politics of her poetry were more generally rooted in the radical and revolutionary milieu in which she found herself, and her participation in the civil rights movement, the struggle against the Vietnam War, and the lesbian and gay liberation movement.

In 1976, Adrienne Rich came out as a lesbian with the publication of Twenty-one Love Poems, which celebrated her sexuality and love for women. She moved in with Michelle Cliff, also a writer, who would be her partner for the next 36 years.

It was in this time period that Rich began to give voice to her radicalizing political consciousness through more theoretical political essays that drew both on her personal experience and her experience in the women's liberation movement. The result was Of Women Born: Motherhood as Experience and Institution, published in 1976, which provided a thorough critique of the way in which ideas of the family and motherhood in particular were used to oppress women and, the resulting alienation of women from their own bodies.

Perhaps her most influential essay, "Compulsory Heterosexuality and the Lesbian Existence," was published in 1980. In this essay, Rich argued against what she saw as the erasure of lesbians from mainstream feminism, challenging the movement to fight for their rights. The essay tears apart the idea that there is anything "natural" about heterosexuality, exposing instead the way in which "compulsory heterosexuality" is used to maintain women's oppression.

Like many other feminist theorists of the time, Rich's political understanding of women's oppression was firmly rooted in patriarchy theory and identity politics. For example, she ends Of Women Born, by declaring:

The repossession by women of our own bodies will bring far more essential change to human society than the seizing of the means of production by workers...We need to imagine a world in which every woman is the presiding genius of her own body. In such a world, women will truly create new life, bringing forth not only children (if and as we choose) but the visions, and the thinking, necessary to sustain, console and alter human existence--a new relationship to the universe.

In this passage, Rich echoes many ideas of the radical feminist movement, counterposing the struggle for women's liberation to workers' struggles for economic justice, despite the fact that, as she later acknowledges, the vast majority of women are workers. There is an implicit rejection of socialist politics in this, based on a false assumption that Marxism privileges the economic over all else. As Rich was to find out later, this caricature ignores much of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels' writing on women's oppression and the centrality of the struggle for women's liberation to the socialist project.

The passage also reflects the dominance of identity politics in this period, and in particular, the idea that since the "personal" was thought to be "political," one needed only to change one's personal life to initiate broader political change.

RICH'S POLITICAL thought, however, evolved greatly over the course of her life. Like many activists, the demise of the women's liberation movement and the 1980s backlash against women led her to question the movement's political underpinnings, and her own political conclusions.

For example, while Rich was an early advocate of consciousness-raising groups as a mean of radicalizing women, she would later argue that such spaces too often became "a place of emigration, an end in itself," as Alice Echols notes in Daring to Be Bad: Radical Feminism in America 1965-1975.

One major influence in Rich's changing political consciousness was her introduction to the writings of Karl Marx which had a profound impact on her political thought. In fact, in the 1986 reprint of Of Women Born, Rich included a new introduction in which she wrote that she would no longer end the book with the passage quoted above.

Rich continued to be a tireless advocate for women's reproductive freedom and control of their own bodies, and she saw this fight as a catalyst for broader social transformation. But in her new introduction, she argued:

I also believe that this [enormous social transformation] can only happen hand in hand with, neither before nor after, other claims which women and certain men have been denied for centuries: the claim to personhood, the claim to share justly in the products of our labor, not to be used merely as an instrument, a role, a womb, a pair of hands or a back or a set of fingers; to participate fully in the decisions of our workplace, our community; to speak for ourselves, in our own right.

In a 1997 essay in the Los Angeles Times, she writes,

Marxism has been declared dead. Yet the questions Marx raised are still alive and pulsing, however the language and the labels have been co-opted and abused. What is social wealth? How do the conditions of human labor infiltrate other social relationships? What would it require for people to live and work together in conditions of radical equality? How much inequality will we tolerate in the world's richest and most powerful nation? Why and how have these and similar questions become discredited in public discourse?

While Adrienne Rich is remembered primarily as a poet and activist of the 1960s and '70s, she was no less vocal, nor less active in the political movements of the '80s, '90s and 2000s--despite the onset of rheumatoid arthritis which would take an increasing toll on her life and work, and would ultimately lead to her death.

She participated in protest movements against the first Gulf War, U.S. intervention over Kosovo and George W. Bush's invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan. The poem "Wait," written in 2003 on the eve of the Iraq invasion, as millions of people around the world protested, is a devastating indictment of the war, and the mass deception used to justify it:

In paradise every

the desert wind is rising

third thought

in hell there are no thoughts

is of earth

sand screams against your government

issued tent hell's noise

in your nostrils crawl

into your ear-shell

wrap yourself in no-thought

wait no place for the little lyric

wedding-ring glint the reason why

on earth

they never told you

Rich also lent her voice to the movement against the prison injustice system and the war on the poor, and for the oppressed and disenfranchised. In 2009, she joined the call for a cultural and academic boycott of Israel because of her outrage at Israel's continued war on Palestinians.

For Rich, poetry was not the domain of the affluent or the few, but rather belonged to the 99 percent. Her 2009 poem, "Ballade of the Poverties," is a moving tribute to the myriad needs that afflict working people around the world. She writes,

There's the poverty of the cockroach kingdom and the rusted toilet bowl

The poverty of to steal food for the first time

The poverty of to mouth a penis for a paycheck

The poverty of sweet charity ladling

Soup for the poor who must always be there for that

There's poverty of theory poverty of swollen belly shamed

Poverty of the diploma or ballot that goes nowhere

The poem concludes with an indictment of (and warning to) the 1 percent "who travel by private jet like a housefly / Buzzing with the other flies of plundered poverties."

RICH NEVER let the lure of fame or prize money coopt her political conscience. When she was awarded the National Book Award for Poetry (along with Allen Ginsberg), she refused to accept it on her own. Instead, she accepted it along side Audre Lorde and Alice Walker, two other nominees. Together, the three accepted the award on behalf of all women.

In 1997, she also famously refused to accept the National Medal of the Arts in protest of the policies of the Clinton administration--"because," she wrote, "the very meaning of art, as I understand it, is incompatible with the cynical politics of this administration." She continued:

There is no simple formula for the relationship of art to justice. But I do know that art--in my own case, the art of poetry--means nothing if it simply decorates the dinner table of power which holds it hostage. The radical disparities of wealth and power in America are widening at a devastating rate. A president cannot meaningfully honor certain token artists while the people at large are so dishonored.

Expanding on her decision to refuse the award and her understanding of art in an article titled "Why I Refused the National Medal for the Arts," published in the Los Angeles Times book section, Rich wrote:

And what about art? Mistrusted, adored, pietized, condemned, dismissed as entertainment, auctioned at Sotheby's, purchased by investment-seeking celebrities, it dies into the "art object" of a thousand museum basements. It's also reborn hourly in prisons, women's shelters, small-town garages, community college workshops, halfway houses--wherever someone picks up a pencil, a wood-burning tool, a copy of "The Tempest," a tag-sale camera, a whittling knife, a stick of charcoal, a pawnshop horn, a video of Citizen Kane, whatever lets you know again that this deeply instinctual yet self-conscious expressive language, this regenerative process, could help you save your life.

"If there were no poetry on any day in the world," the poet Muriel Rukeyser wrote, "poetry would be invented that day. For there would be an intolerable hunger." In an essay on the Caribbean poet Aime Cesaire, Clayton Eshleman names this hunger as "the desire, the need, for a more profound and ensouled world.

For Rich, this commitment to a poetry from below--a poetry which could be the literary expression of a revolutionary consciousness, of the struggles and aspirations of millions, as well as the love and passion which make life worth living--was the principle that guided her artistic work. As she wrote in the poem "Dreamwood," poetry / isn't revolution but a way of knowing / why it must come..."

In remembering Adrienne Rich, we remember a poet who maintained an inexhaustible faith in the radicalizing potential of art, the liberatory potential of humanity and the deep connection between the two. As she explained in a 2006 essay, "Legislators of the world," published in The Guardian:

[W]hen poetry lays its hand on our shoulder we are, to an almost physical degree, touched and moved. The imagination's roads open before us, giving the lie to that brute dictum, "There is no alternative."...

Poetry has the capacity to remind us of something we are forbidden to see. A forgotten future: a still uncreated site whose moral architecture is founded not on ownership and dispossession, the subjection of women, outcast and tribe, but on the continuous redefining of freedom--that word now held under house arrest by the rhetoric of the "free" market. This ongoing future, written off over and over, is still within view. All over the world its paths are being rediscovered and reinvented.

The best way to honor the life and work of Adrienne Rich is to fight for that future.