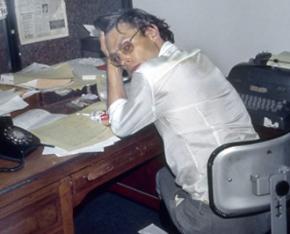

A modern-day muckraker

remembers the life of journalist Alexander Cockburn.

THE RADICAL media lost one of its most powerful voices when Alexander Cockburn died last weekend after a battle with cancer.

For more than four decades since his move to the U.S. from Britain in 1972, Cockburn's writing was a constant presence for anyone on the left in the U.S.

And I mean constant. All told, Cockburn lived and worked in the U.S. for something over 2,000 weeks--and if more than a few dozen of those weeks went by without a new article from him, I'd be surprised. His voice was never silent and he never went unpublished--in spite of the fact that the gatekeepers of the mainstream media had almost as much contempt for him as he had for them.

Cockburn was born in Scotland, grew up in Ireland and went to school in England. His parents came from upper-class families, but his father, journalist Claud Cockburn, was a member of the British Communist Party who wrote for the Daily Worker, among other left and mainstream publications. As a student and then a journalist himself in 1960s Britain, Alex gravitated to left-wing politics and publications like New Left Review. By the early 1970s, he had moved to the U.S.

I first started reading Cockburn at the beginning of the 1980s while he was writing a media criticism column for the New York City alternative weekly, the Village Voice. The Voice was home to great investigative journalists like James Ridgeway, too--but Alex was the reason I knew what newsstands and bookstores in Chicago sold the Voice.

No one was better at nailing the dishonesty and hypocrisy of the powerful, demolishing their lame arguments or just plain spitting venom at a hated target. Open his book Corruptions of Empire, a collection of journalism from this era, to random pages, and you find one gem after another. Like this from a 1985 article about press baron Rupert Murdoch and his troubles with the Federal Communications Commission: "It's hard to believe that Rupert Murdoch truly intends to sell the New York Post. It would be like Dracula selling his coffin."

Or, in 1981, a comparison of the U.S. media's coverage of the strike of PATCO air traffic controllers, declared illegal by the Reagan administration, and the strikes of the Solidarnosc union movement in Stalinist Poland, a satellite of Washington's arch-enemy, the USSR:

Washington Post, Union-Busting Edition: "The air traffic controllers strike is a wildly misconceived venture that deserves the government's extraordinary severe response. A strike against an essential public service is always wrong in principle."

Washington Post, Freedom-Loving Edition: "The Polish shipworkers strike is an extraordinarily gallant venture, and that makes the Polish government's fierce response all the more heavy-handed and abhorrent to all friends of freedom. The right to strike is one of the inalienable attributes of a democratic society."

COCKBURN GOT the boot from the Voice in 1983. The paper claimed it was because he took a $10,000 fellowship to write a book, a journalistic conflict of interest. Cockburn argued persuasively that the real problem was the fellowship came from the Institute of Arab Studies--and that his uncompromising support for the Palestinian cause against Israel's apartheid offended the pro-Zionist management at the Voice.

Much of Cockburn's writing at this time was about U.S. imperialism, as the Reagan administration attempted to reassert Washington's power a decade after the American defeat in Vietnam. Cockburn provided exhaustive commentary on the covert and not-so-covert war on left-wing struggles in Central America and the U.S. government's support for death squads and dictators.

But he really stood apart in his outspoken opposition to the Israeli regime. This was still an era of knee-jerk loyalty to Israel--from the U.S. government, of course, but also from U.S. liberals and even some who considered themselves on the left. Cockburn tolerated none of it--his writings gave no quarter when it came to Palestine.

At this point, the broadcast media had yet to be transformed by 24-hour cable TV news, so network shows like ABC News' Nightline, hosted by Ted Koppel, were still required viewing for anyone who cared about politics.

Cockburn wrote brilliantly about how the for-and-against format of Nightline or PBS's MacNeil Lehrer News Hour hid the fact that the range of political views tolerated in the mainstream media was incredibly narrow. But he was also so skilled as a journalist that he was occasionally asked to appear.

I remember Alex on one of Nightline's featured town-hall discussions. Unlike the respectable guests who were live in the auditorium, he was consigned to a remote hookup, so he could speak only when spoken to by Koppel. Yet with a fraction of the time that the establishment windbags took to speak, Alex still won the debate hands down.

After the Voice, Cockburn took a featured column at the Nation magazine, which he wrote until his death.

But the Nation was never his political home. Cockburn was constantly at war with the pro-Democratic Party liberalism found regularly in its pages.

He saw himself as an enemy of Democrats as much as Republicans because the two parties--whatever their "dime's worth of difference," in the phrase that later served him as a book title--were bound together by their role in a bipartisan political establishment responsible for war, poverty and oppression. Time and again, Cockburn would investigate the Democratic heroes celebrated in places like the Nation and uncover their scandalous betrayals.

A lot of that dirt on the Democrats made it into my favorite of Cockburn's many books, Washington Babylon, co-written with Ken Silverstein and published in the midst of the Clinton years.

A playful take on the trashy Hollywood Babylon, the Cockburn and Silverstein version was an encyclopedia of political sleaze--and plundered many a time for Socialist Worker articles, I don't mind admitting. There were indispensible dossiers on the powerbrokers of both parties, plus the unelected bureaucrats, lobbyists and think-tank blowhards who shape government policy as much as elected officeholders--and, of course, the lapdogs of the establishment press.

A few years before, Cockburn and Silverstein had started collaborating on a political newsletter called CounterPunch. The aim was to give the editors--Jeffrey St. Clair later took over for Silverstein--and a few select contributors a forum to write what they wanted, without the compromises for commercial or political considerations at publications like the Nation.

The newsletter was popular among its subscribers, but CounterPunch later became much more important.

As a website, CounterPunch.org didn't have the space constraints imposed by the newsletter's six- or eight-page length, and it could publish every day, without worrying about how to pay for printing or postage. With dozens of writers contributing--SW's among them--CounterPunch became the main website of the U.S. radical left, with many tens of thousands of readers every day.

CounterPunch was an important part of a fundamental shift in the media terrain, as Cockburn and St. Clair wrote in a 2007 collection of articles:

[T]he old David vs. Goliath struggle of the left pamphleteers battling the vast print combines of the news barons has equaled up...Thirty years ago, many of these pieces, challenging the official nonsense peddled in the mass-market media, would have been doomed to small-circulation magazines, or a 30-second précis on Pacifica radio...Not any more. We can get a news story from a CounterPuncher in Gaza or Ramallah or Oaxaca or Vidharba, and have it out to a world audience in a matter of hours.

I THINK Alex would have hated a reverent tribute that skipped over the points where we at Socialist Worker disagreed with him, sometimes very sharply. There were a few of them--more so in the last 10 years, or so it seemed to me.

In the middle of the 2000s, Cockburn stunned CounterPunch readers with a furious denunciation of the science of global warming. As I heard the story, a climate change denier got his ear on a Nation magazine cruise, and from that point on, he never turned back. Global warming was a hoax perpetrated by mainstream environmental groups to raise money, and nothing anyone wrote in response--not even his CounterPunch coeditor, Jeffrey St. Clair, every bit as good a muckraker as Cockburn--could shift him.

On questions of women's oppression, Cockburn's writings ranged from adequate to weak to awful. One ugly low point was a 2009 CounterPunch feature in which he suggested that the right-wing dingbats complaining about alleged death panels set up by Barack Obama's health care law had a point--since "the major preoccupation of liberals for 30 years has been the right to kill embryos." Abortion, Cockburn wrote, "is now widening in its function as a eugenic device." It was impossible to read without wanting to break things.

Cockburn always seemed to reserve his deepest contempt for those who claimed in words to stand for justice or freedom, but who compromised to curry favor with business or stay in the good graces of the Democratic Party. This scorn served him well in unmasking the establishment liberals. But he seemed to conclude from this that right-wingers--particularly of the libertarian variety--were the more genuine allies.

Thus, for example, during the 2008 presidential campaign, several CounterPunch writers championed Republican Ron Paul as the only real antiwar presidential candidate in either party. Paul was against the U.S. "war on terror"--though on the basis of isolationism, not for the same reasons as the left. But he was also a racist, anti-immigrant, anti-union, anti-choice bigot who wanted to dismantle the federal government. It was hard to understand how CounterPunchers who wrote passionately against immigrant-bashing or the bipartisan budget-cutters could overlook all this and focus only on his antiwar position.

The list of differences with Cockburn could go on. I think maybe one reason they remain stingingly fresh in mind is because he argued just as hard on these questions as any other. Alex never wrote anything halfway--he never met a political debate that he didn't wade into, guns blazing.

But that was also a source of his contribution to the U.S. left. Especially in difficult or politically murky times--the turn to the right under Reagan and the rehabilitation of U.S. imperialism, the collapse of a liberal opposition during the Clinton years, the stampede to the right after September 11 and the launching of the "war on terror"--Cockburn refused to ever accept any sign of compromise or retreat.

He never stopped speaking truth to power--and the left we need to build for the struggles of tomorrow will be stronger for the battles of the past that he helped to define and crystallize with his writing.