Igniting a war to free the slaves

The unveiling of the Emancipation Proclamation 150 years ago this fall marked a turning point in the history of the American Civil War, writes .

ON SEPTEMBER 22, 1862, in the aftermath of a bloody Northern victory at the Battle of Antietam, President Abraham Lincoln issued the preliminary version of the Emancipation Proclamation, which proclaimed that all slaves in the Southern states still in rebellion against the U.S. would be "forever free" as of the turn of the New Year.

It was a pivotal moment in the American Civil War--the point at which the conflict changed from a struggle for national unity into a revolutionary war to free the slaves.

In some ways, Lincoln's bold action had been a long time in coming. The president's election in 1860--as the presidential candidate of the recently formed Republican Party, running against two candidates representing the Northern and Southern wings of the pro-slavery Democrats--precipitated the secession of the Southern slave states and led to the first shots of the Civil War being fired only weeks after Lincoln took office.

But the new president insisted that the federal government in the North was fighting above all to "preserve the Union." In his first Inaugural address, Lincoln said he would support a Constitutional amendment guaranteeing the legality of slavery in the Southern states where it existed as long--as the South came back to the Union. The war had been raging for 18 months by the time Lincoln decided to act decisively against slavery.

Many abolitionists had become frustrated with Lincoln's refusal to confront the question of slavery, which they rightly saw as both the cause of the war and the mainspring of the Confederacy's strength.

As Thaddeus Stevens, the leading radical in Congress, put it in January 1862:

How can the war be carried on so as to save the Union and constitutional liberty? Prejudice may be shocked, weak minds startled, weak nerves may tremble, but they must hear and adopt it. Those who now furnish the means of war, but who are the natural enemies of slaveholders, must be made our allies. Universal emancipation must be proclaimed to all.

LINCOLN'S RELUCTANCE to embrace abolition reflected the contradictory character of the party he represented. Although the Republicans had come to power on the basis of growing Northern hostility to the southern "slave power," most of its leading figures weren't abolitionists. Many hoped, as Lincoln did, to put slavery on the path to gradual extinction, but they doubted the legality of direct interference with the property rights of slaveholders.

Lincoln also faced political considerations. He wanted to hold together the broadest possible coalition against secession and Confederate independence, and this led him to avoid radical measures. In particular, he wanted to maintain the goodwill of "loyal" slaveholders in Border States like Maryland and Kentucky.

Events in Missouri in the summer of 1861 showed just how far Lincoln was prepared to go to maintain an anti-Confederate alliance that tolerated slavery. Following a number of setbacks in that state, a northern officer, Major Gen. John C. Frémont, unilaterally declared the emancipation of the slaves of all rebel sympathizers. Lincoln not only rescinded Frémont's order, but he removed the radical officer from command.

Ever the pragmatist, Lincoln summarized his view of the slavery question in a letter to radical newspaper editor Horace Greeley in the summer of 1862:

My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that.

Yet just one month later, Lincoln unveiled the Emancipation Proclamation. Two factors forced Lincoln and his government to reconsider their conservative war aims.

The first was a series of serious military defeats for the Union Army. Confederate victories at Bull Run, Wilson's Creek, Ball's Bluff and other battlefields demonstrated conclusively that the South would not concede without a real fight, and that drastic action would be necessary to win the war.

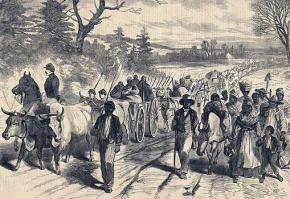

Secondly, and just as importantly, the slaves had no intention of waiting for Lincoln to act. From the moment word of the war reached them, thousands of slaves across the South became convinced that their future was bound up with the course of the conflict--and decided to strike out for freedom.

When Northern troops made their way into Southern territory, therefore, they encountered slaves who saw them as potential allies. At first, racist white officers and soldiers refused to help these Black fugitives. Northern commanders even offered to help put down slave insurrections should the slaves decide to rise against their masters.

But the logic of the situation soon dictated a change in policy. In northern Virginia, during the summer of 1861, Union troops under Gen. Benjamin Butler encountered runaway slaves who had been forced to work building fortifications for the Confederate Army. Were Northern soldiers really going to do their enemies the favor of returning these military laborers?

Butler decided against this and declared the slaves "contraband of war"--property that, having been used in the rebellion against the U.S., was liable to seizure by Union forces. Within weeks, 1,000 fugitive slaves had reached Butler's camp.

In Washington, Lincoln's government began to pass legislation recognizing the new situation on the ground. The Confiscation Acts of 1861 and 1862 gave legal cover to Butler's "contraband" argument, and the Militia Act allowed Union officers to employ escaped slaves in the Northern war effort. The new anti-slavery mood led Congress to ban slavery in the Western territories and enact a compensated emancipation plan for slaves in the nation's capital.

BY JULY 1862, Lincoln had begun to consider the possibility of emancipation as a war measure, but members of his Cabinet urged the president to wait to announce it until the Union had won a major victory in the field. The Battle of Antietam in September offered just such an opportunity.

In truth, Antietam was no smashing victory for the North. Robert E. Lee's Confederate Army of Northern Virginia had launched an invasion of Maryland, pursued by a large Union force under the command of the arrogant but timid Gen. George McClellan.

On September 17, the outnumbered Confederate forces fought McClellan's troops to a standstill in one of the bloodiest battles of the whole war. Although neither side could claim a decisive advantage, Lee was forced to retreat back into Virginia, and Lincoln had his chance.

On September 22, therefore, Lincoln declared that, unless the states in rebellion returned to the Union by the end of 1862, their slaves would be "henceforth and forever free." The Emancipation Proclamation would also allow Black men to join the Northern armies as soldiers.

Lincoln was still far from the radical abolitionists like Frederick Douglass who urged such action from the beginning--though by the end of the war in several more years, he was resolute against all suggestions of compromise that slavery should be abolished.

Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation in recognition of a transformation of the war that was already underway. In this respect, Lincoln was right when he wrote in one letter that he couldn't claim "to have controlled events, but confess plainly that events have controlled me."

The events of the Civil War drove Lincoln to take revolutionary action. But he did take action--while some fellow Republicans with a stronger record in support of abolition hesitated.

And indeed, the Emancipation Proclamation had the effect Lincoln expected. The Northern Army was formally transformed into an army of liberation, since wherever it advanced in the South, the promise of emancipation could be enforced. Black slaves fled to the Northern battle lines in greater numbers--and the contribution of Black soldiers to the Northern war effort became more and more central.

With the announcement of the Emancipation Proclamation, the Civil War officially became a war for the freedom of 4 million slaves--and a process of social revolution began.