Legislators against testing?

reports on some unexpected challenges to testing in Texas.

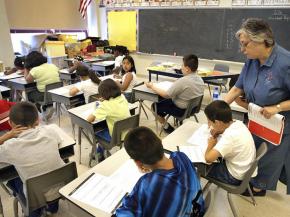

STANDARDIZED TESTING has been on the minds of students, teachers and parents for years, but this year, it also seems to be on the mind of the Texas legislature. The start of the 83rd Texas legislative session has kicked off with a flurry of new bills aimed at changing standardized testing in the state.

"By now, every member of this house has heard from constituents at the grocery store or the Little League fields about the burdens of an increasingly cumbersome testing system in our schools," said Speaker of the House Joe Straus. "To parents and educators concerned about excessive testing: The Texas House has heard you."

As of last week, 20 bills had been filed that seek to change the way tests are given and used. The bills vary wildly, from reducing the number of exams required to graduate to a proposed two-year moratorium on testing. But parents, teachers and students have been criticizing these tests for years. Why is this issue finally being taken up by the state legislature?

In part, the legislation is a reaction to the state and national backlash against testing. Across the country, people are standing up to the high-stakes tests that have been strangling our schools. This includes the boycott of the Measures of Academic Progress (MAP) tests by Seattle teachers and the decision by parents across the country to have their children opt out of tests.

Texans Advocating for Meaningful Student Assessment (TAMSA) notes that parents in particular began to speak out when Texas changed the state assessment last year from the Texas Assessment of Knowledge and Skills (TAKS) to the supposedly more rigorous State of Texas Assessments of Academic Readiness (STAAR).

A year ago, even then-current Texas Education Agency Commissioner Robert Scott spoke out against high-stakes testing in schools, calling the current testing regime a "perversion" of what had originally been intended by the bills.

As TAMSA member and former board president of Spring Branch Independent School District Susan Kellner told the Star-Telegram, "Over time, parents got fed up...When they went to 15 [end-of-course exams], it blew the powder keg."

One issue in particular that has parents upset is the so-called "15 percent rule," which mandates that 15 percent of a student's final course grade be determined by their performance on STAAR end-of-course exams. This rule has especially concerned suburban, middle-class parents who are worried about the effects of this rule on their children's grade point averages (GPAs), and thus their admission to college.

After strong resistance against the rule by groups last year, the implementation of the 15 percent rule was postponed for one year. Now, several bills in the state House and Senate have called for its repeal.

THOUGH MANY of the bills currently being proposed in the legislature seek a reduction in high-stakes testing and accountability measures, grassroots education reformers should be careful in their assessment of what this means.

Several of the bills propose replacing state standardized tests with national tests, such as the SAT or ACT. Though this might be a change in testing, few would argue that it's a true reform. As teacher activist Brian Jones recently explained, "The attempt to quantify learning and teaching in a standardized manner is extremely expensive; takes up weeks and, in some places, months of time in school; narrows the curriculum; undermines the intrinsic joy of learning; and leads to a culture of corruption and cheating."

All of these criticisms apply to national tests as well. The problem is not type of test, but rather the act of standardized testing itself.

Though legislators are seeking to reduce the testing regime in the state, many still believe these tests are an important part of our education system. For example, Sen. Leticia Van de Putte (D-San Antonio), who co-authored a bill that includes provisions that would reduce end-of-course exams from 15 to three, has stated that she remains committed to school accountability, and seeks to create "a dynamic college- and workforce-readiness accountability system."

A steady workforce is also the concern of Texas Association of Business President Bill Hammond, who has been a strong supporter of high-stakes standardized testing for years and recently called for a standardized accountability system for the state's pre-kindergarten programs. This year, though, even he is calling for a reduction in the number of STAAR end-of-course exams.

The fact that Hammond backed down on this issue demonstrates the strength of the resistance to testing, but grassroots reformers should note that the two exams he wants eliminated are in world history and geography--subject areas Hammond likely believes his future workers don't need.

Demonstrating his lack of concern for the importance of history and social studies in our schools, Hammond told reporters, "If we could get 'em past the Civil War, we'd be doing pretty good."

Another concern with these bills relates to funding. The proposed 2014-2015 House budget currently allocates no funding for the administration of STAAR, which legislators claim is a response to voter concerns around high-stakes testing. Though this may have some truth to it, the bigger motivation for House Republicans is to reduce spending at all costs. This includes slashing funding for public schools in a state that the National Educators Association recently found ranks 45th in per-student education spending.

The budget proposal is also unrealistic, given that No Child Left Behind requires that certain tests be given annually for schools to receive federal funding. With that law still intact, the House budget won't eliminate testing. Instead, it will shift the burden of funding to local districts that are already dealing with budget shortfalls. This isn't a budget that supports our children's education, and it isn't one that should be celebrated as such.

A FEW miles away from where the state legislature in the capital of Austin, 20 parents, teachers and community members met recently to discuss "The Schools Our Kids Deserve" at an event put on by grassroots education group Occupy AISD (Austin Independent School District).

The meeting began with participants discussing and drawing pictures of their ideal school. With the exception of one group that drew a dumpster with STAAR test materials, none of the groups mentioned high-stakes testing as part of their ideal school.

Instead, people spoke about small class sizes, music and art classes, community gardens and libraries filled with books. They spoke about the need for schools to be well funded so they could provide support and services for all, as well as the desire for curriculum that engaged the whole child and the whole community. One middle school teacher articulated his vision as "having a school be part of the community and having the community be part of that school."

After sharing these visions, the group moved into a discussion of how to begin to build these schools. The group shared many ideas, from protesting the legislature at the upcoming Save Texas Schools rally to showing solidarity for the Seattle teachers boycotting the MAP tests.

Rather than depending on the legislature, they committed to fighting for what's best for Texas children and Texas public schools.