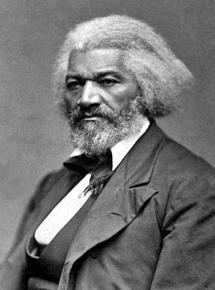

A mighty voice for freedom

tells the story of the great Black abolitionist Frederick Douglass.

AS REMARKABLE as it may seem, Frederick Douglass was for decades written out of the history of how slavery ended in the United States.

Major historical works of the early 20th century, such as James Ford Rhodes' History of the United States and John B. McMaster's History of the People of the United States, hardly mention the former slave who became one of the most far-sighted abolitionist leaders and possibly the greatest radical orator in American history.

Fortunately, the civil rights struggles of the mid-20th century rescued Douglass from historical obscurity. Along with a generation of more radical historians, such as Herbert Aptheker, Benjamin Quarles and Philip Foner, the civil rights movement elevated Douglass to his rightful place in American history. In 1963, Ebony magazine put a portrait of Douglass on its cover and declared him "the father of the protest movement" and "the first of the 'Freedom Riders' and 'Sit-Iners.'"

Fast forward to today, and there has been a regression. Nearly everyone in the U.S. recognizes Douglass as historically important, yet few are taught much about the history he helped to create. Schools and streets may carry the name of Frederick Douglass, yet the real story of his life--along with the history of slavery, abolitionism and the Civil War--remains little known or deeply misunderstood.

DOUGLASS WAS born a slave in February 1818 and came of age in a world that was changing rapidly. The early 19th century saw a transformation of the U.S. economy driven by the rise of the cotton economy and the resulting expansion of plantation slavery.

King cotton became massively profitable with the invention of the cotton gin in 1793, and the profits from slave-produced cotton and the textile industry fueled the industrial revolution getting underway in England and the Northern U.S. Along with the growth of profits came a growth in the Southern slave system's scope and reach.

Douglass lived on the periphery of this system rather than at its heart. Born on a plantation on Maryland's Eastern Shore, Douglass spent his early life in this border state, where the slave system was smaller and weaker than in most other Southern states. Ninety-seven percent of slave owners in Maryland owned five slaves or less.

Slavery in Maryland coexisted uneasily alongside a growing system of wage labor. In the booming urban center of Baltimore, where Douglass lived for part of his youth, this system played an increasingly important role.

The city was rich in political and cultural activities. For instance, Benjamin Lundy published an early abolitionist newspaper there called The Genius of Universal Emancipation from 1824 until 1835.

Maryland was home to a large and growing free Black population. Forty-five percent of all Maryland Blacks were free by 1850--and Baltimore's free Black population was the largest in the country.

The tensions between slavery and early industrial capitalism in Maryland mirrored the growing contradictions between the two systems nationally. Historians such as Barbara J. Fields have noted that these tensions within "middle ground" states like Maryland "imparted an extra measure of bitterness to enslavement, set close boundaries on the liberty of the ostensibly free, and played havoc with bonds of love, friendship and family among slaves, and between them and free Black people."

These conditions shaped Douglass's early life, during which he was secretly teaching himself to read and developing his anti-slavery worldview. Living in such close proximity to a large free Black population--one with a reputation for labor militancy, no less--impacted Douglass in important ways. It's no accident that Maryland produced not only Douglass, but other great anti-slavery leaders like Harriet Tubman and Henry Highland Garnet.

The existence of this free Black population directly impacted Douglass's life in at least one other crucial way. Douglass' first wife, Anna Murray, was a free Black woman living in Baltimore. After they met in 1838, when Douglass was 20, Murray came up with the plan for how he would flee the state and escape slavery. As part of the escape plan, Douglass would disguise himself as a sailor, wearing a uniform Murray had borrowed from a free Black seaman.

Douglass and Murray fled first to New York, then to New Bedford, Mass. Here, Douglass came into direct contact for the first time with the abolitionist movement that would define the next three decades of his life.

WITH THE expansion of slavery in the first half of the 19th century came new troubles for the slave owners. The trickle of runaway slave became a flood as thousands escaped North every year on the Underground Railroad. Slave rebellions increased across the South--the most famous of which was led by Nat Turner in Southampton, Va., in August 1831.

This slave resistance was a critical factor in the development of the movement for the abolition of slavery. By 1838, the year of Douglass' escape from slavery, the movement was blossoming. Historians estimate that 1,400 anti-slavery societies existed around the country as of that year, with at least 112,000 members. The movement became more radical as Blacks came to play a more central role. Abolitionists who believed slavery would gradually die out on its own or that freed slaves should be sent back to Africa were pushed to the margins.

The movement's best-known leaders were whites, like William Lloyd Garrison, but the free Black population became its backbone. Thousands of Blacks subscribed to abolitionist newspapers such as Garrison's The Liberator--which Douglass later said was "my meat and my drink."

The main split in the abolitionist movement encountered by Douglass in the 1840s was between those who favored a political strategy for the movement, and those who opposed involvement in the political system and saw the Constitution as a pro-slavery document--"a pact with the devil," as Garrison called it.

Garrison's faction was more prominent early on, and it was this group that Douglass gravitated to. As Douglass developed himself as an anti-slavery orator, growing audiences flocked to hear him speak. Thousands read his newspaper articles and essays. Douglass' insight into the workings of the slave system and his clear calls for justice and equality were unmatched, even in a movement made up of talented writers and speakers.

But the ideas of Garrisonians were contradictory. They combined the harshest denunciations of slavery and the American political system with agitating for the North to remove itself from any connection with the South--to break away from the Southern states and form a separate country, free of the taint of slavery.

This wasn't rooted in material reality at all. Furthermore, the Garrisonians were pacifists and felt the best and only way to spread the anti-slavery movement was by nonviolent "moral persuasion."

As the conflict between North and South grew more intense, the force of events moved Douglass away from Garrison and towards a strategy of political agitation and armed force to end slavery.

Black leaders played a more and more important role in the struggle. Alongside Douglass were fighters such as Garnet and David Walker, whose militant calls for slave rebellion undoubtedly influenced Douglass.

Yet the views of Black abolitionists varied as well. Some, such as Garnet, became ardent advocates of colonization as a way to build an independent Black society, free of white racism. Douglass rejected this view and insisted that the Black struggle was rooted in the U.S. He began to argue that the democratic values articulated in the U.S. Constitution, though not honored in practice, could be a powerful weapon with which to attack slavery.

Douglass began to chart his own path. In 1847, he founded his first newspaper, the North Star. Though he reaffirmed his commitment to Garrisonian wing of the movement as late as September 1849, it was clear that he was following a different trajectory. Speaking in Boston that same year, he rejected his earlier insistence on nonviolence, saying that he would "welcome the intelligence tomorrow, should it come, that the slaves had risen in the South, and that the sable arms which had been engaged in beautifying and adorning the South were engaged in spreading death and devastation there."

By this point, Douglass established himself as a leading voice for freedom and equality--and not only for Black Americans, but for women as well. He frequently spoke and wrote in support of women's equality and the right to vote, and he was present at the Seneca Falls Convention on women's rights.

"WHEN HE spoke, he roared," the historian James Oakes writes of Douglass. Douglass' understanding of American society was deep and multifaceted. He described with unparalleled skill how the slave-owning elite in the South used racism to maintain social control:

The slaveholders...by encouraging the enmity of the poor laboring white man against the Blacks, succeeded in making the white man almost as much a slave as the Black slave himself. The difference between the white slave and the Black slave was this: the latter belonged to one slaveholder, and the former belonged to the slaveholders collectively...Both were plundered, and by the same plunderers...The slaveholders blinded them to this competition by keeping alive their prejudice.

Douglass called out the hypocrisy of all U.S. society, not just the Southern slaveholders. Most famously, he denounced the celebration of the Fourth of July as "a thin veil to cover up crimes which would disgrace a nation of savages."

As time went on, the U.S. veered ever closer to civil war. With every milestone--the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850; the battles of "Bloody Kansas" in 1854; the Supreme Court's Dred Scott decision of 1857; John Brown's October 1859 assault on the U.S. armory in Harper's Ferry; and the election of Abraham Lincoln from the recently formed Republican Party--the conflict between the Southern slave system and the Northern industrial system grew shaper.

During this era, Douglass tirelessly worked for the abolitionist cause, traveling at home and abroad to speak to large audiences. According to one writer, a "partial" list of Douglass' speaking events for just the month of January 1855 included at least 21 addresses, in cities stretching from Maine to Massachusetts to New York to Pennsylvania. Between 1855 and 1863, Douglass gave more than 500 known speeches in the U.S., Britain and Canada.

Douglass was especially keen in recognizing how the conflict between North and South was leading inevitably toward a war that would end slavery. He was relentless in criticizing the shortcomings of Lincoln and the Republicans:

The Republican Party...is opposed to the political power of slavery, rather than to slavery itself. It would arrest the spread of the slave system...and defeat all plans for giving slavery any further guarantee of permanence. This is very desirable, but it leaves the great work of abolishing slavery...still to be accomplished. The triumph of the Republican Party will only open the way for this great work.

But he disagreed with other abolitionists who called for a boycott of the 1860 presidential election. As he wrote a few months before the vote:

I cannot fail to see that the Republican Party carries with it the anti-slavery sentiment of the North, and that a victory gained by it in the present canvass will be a victory gained by that sentiment over the wickedly aggressive pro-slavery sentiment of the country...The slaveholders know that the day of their power is over when a Republican president is elected.

Douglass was proven correct. In response to Lincoln's victory, Southern states began seceding from the Union before he was even inaugurated. Within months, the Civil War Douglass had predicted was underway.

During the war, Douglass played a key role in pressuring Lincoln and the Republicans to make the destruction of slavery a war aim. In particular, he was central to the North's decision to allow Black soldiers to fight for the Union. In a speech to a Black audience in Philadelphia in 1863, Douglass argued that enlisting to fight would advance the cause of equal rights after the war:

Never since the world began was a better chance offered to a long enslaved and oppressed people. The opportunity is given us to be men...Once let the Black man get upon his person the brass letters U. S.; let him get an eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulder, and bullets in his pocket, and there is no power on the earth or under the earth which can deny that he has earned the right of citizenship in the United States...In your hands, that musket means liberty.

Throughout the Civil War and the period of Reconstruction that followed, Douglass fought not only for emancipation, but full equality for the Black population. When other abolitionists were ready to declare victory, Douglass insisted that the struggle must continue "until the Black man has the ballot."

It is true, as historians have argued, that Douglass' politics moderated later in his life, particularly after the end of Reconstruction in South. Yet more than any other abolitionist, Douglass understood the connection between anti-racism and the struggle against all forms of oppression. His most famous quote remains apt to the world we live in today, and our struggle to transform it:

If there is no struggle, there is no progress. Those who profess to favor freedom, and yet deprecate agitation, are men who want crops without plowing up the ground. They want rain without thunder and lightning. They want the ocean without the awful roar of its many waters. This struggle may be a moral one; or it may be a physical one; or it may be both moral and physical; but it must be a struggle. Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will.