The lessons of Scottsboro

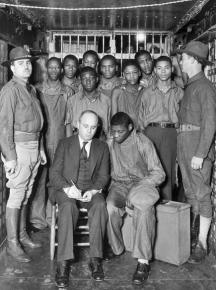

tells the story of the campaign, organized against all odds, to keep nine innocent Black teenagers from being executed in Alabama's death chamber.

ALMOST 80 years after the trial that condemned nine innocent Black teenagers to death for allegedly raping two white women, the Alabama parole board has finally issued a pardon to the last three Scottsboro Boys.

The old saying that "the wheels of justice turn slowly" is a grotesque understatement in this case.

The Alabama justice system's eight-decades-too-late decision only underscores the Herculean antiracist struggle to save the nine youths from a legal lynching in the 1930s Jim Crow South.

The Scottsboro Boys survived because of a fight waged across the country, with protests and other actions that brought the realities of Southern racism into the spotlight at the same time that they exposed the racism that existed in every corner of U.S. society.

The campaign to defend the Scottsboro Boys centered around the basic idea that justice would not and could not be won in the courts--especially the courts of Alabama--but had to be the won in the streets. The protest movement, initiated by members of the Communist Party (CP), became a focal point for antiracist organizing in the 1930s and drew support around the country and around the world.

This one case highlighted the many ways racism is woven into the institutions and beliefs of U.S. society--for example, the myth of the Black rapist preying on virtuous white womanhood, or the idea that the police and courts dispense justice evenhandedly.

But there is another lesson to be learned about Scottsboro: that a determined campaign for justice, which put a premium on mobilizing Blacks and whites together to fight racism alongside one another, could defy the odds and stop the Alabama death machine from claiming nine more victims.

ON MARCH 25, 1931, nine Black youths hopped a freight train. Like many unemployed people of the day, Black and white, the young men, aged 13 to 19, were simply searching for work, and needed transportation to find it.

On the train, they got in a fight with some white youth, and the whites complained to the nearest stationmaster. A posse was called to apprehend the young Black men--it met the train in Paint Rock, Ala. When they all got off the train, two young white women who had also hopped the freight, Ruby Bates and Victoria Price, also disembarked.

The young men were taken to Scottsboro, the seat of Jackson County, where they were met by a racist lynch mob--and now, the charge wasn't just fighting, but the rape of Bates and Price as well. The National Guard was called in to protect the nine from a mob lynching--so that their legal lynching could be carried out.

Jim Crow justice was swift in its judgment of the nine Black youths. They went to court 12 days after their arrest, and their four trials lasted a total of just four days.

Decisive testimony came from the two white women, who lied on the stand about their alleged assault. In this lynch-mob setting before an all-white audience, it was little surprise that the sentence was death for all except 13-year old Roy Wright. "The courtroom," said 18-year-old defendant Haywood Patterson, "was one big smiling white face."

If the trial were the end of the story, we would never have heard of the Scottsboro Boys. But it wasn't--thanks to a campaign that mobilized thousands of ordinary people to take on this racist injustice. Rather than rely on convincing politicians and the courts that an injustice had been done, the CP-led campaign instead relied on working people, Black and white, coming together to oppose this injustice.

After the death sentences were announced, the CP called for a nationwide protest movement, and the party's legal defense wing, the International Labor Defense (ILD), contacted the Scottsboro Nine and their families about representing them in court.

The CP's strategy was to organize the best legal defense available, while simultaneously building a national activist campaign--with the understanding that pressure and mobilization from below was necessary to save the nine. As a Liberator editorial argued at the time: "There can be no such thing as a 'fair trial' of a Negro boy accused of rape in an Alabama court. Anyone who thinks otherwise is a fool. Anyone who says otherwise is trying to deceive."

The campaign put the Scottsboro Boys and their families at the center of the struggle. Family members toured the country to speak about the case, sometimes attracting thousands to hear them. The defense campaign joined forces with various Black organizations, including community groups, churches and fraternal organizations, to mobilize multiracial crowds of protesters in support of the Scottsboro Boys.

For the CP, which called Scottsboro a "legal lynching," taking up the case was about more than winning justice for nine innocent teenagers. It was also about shining a light on the racism of U.S. society. "Precisely because the Scottsboro case is an expression of the horrible national oppression of the Negro masses," wrote the Daily Worker, "any real fight...must necessarily take the character of a struggle against the whole brutal system of landlord robbery and imperial national oppression of the Negro people."

The campaign was also about proving in action how Blacks and whites could come together to fight racism.

The CP's bold approach to organizing--prioritizing mass action and an uncompromising condemnation of racism--stood in sharp contrast to the NAACP, which at first avoided taking up the campaign at all. Later, NAACP leaders tried to wrest control of the defense campaign from the CP by convincing a few defendants to switch their representation. But the defendants' families, who had experienced organizing with the communists, convinced their sons otherwise.

Likewise, when Black Southern ministers tried to take over the fight from the ILD, the Scottsboro families continued to support the CP-led defense. "For the first time in their lives, white men were not telling them what to do, but asking their support, on the basis of complete equality," wrote Dan T. Carter in Scottsboro: A Tragedy of the American South. "The contrast with the Minister's Alliance was all the more striking, since neither Roddy nor Stephens [of the Alliance] had bothered to talk with them about the cases."

When the communists who led the defense campaigns faced red-baiting and race-baiting, this was met with fierce defenses from the people who worked with them closest. "They tried to tell me that the ILD was low-down whites and Reds," Haywood's mother, Janie Patterson, told a rally in New Haven, Conn. "I haven't got no schooling, but I have five senses, and I know Negroes can't win by themselves."

Patterson said, "I don't care whether they are Reds, Greens or Blues. They are the only ones who put up a fight to save these boys, and I am with them to the end."

AROUND THE country, the CP organized rallies and demonstrations. While the first events were small, turning out mostly party members, outrage over the case among Black workers fueled larger turnouts as the campaign progressed.

Nevertheless, some of the official policies of the Communist Party at the time--which, under instructions from the Stalinist government in Russia, were dominated by a strategy of exposing liberals at all costs--held it back during some of the Scottsboro campaign. For example, when Clarence Darrow, the famous lawyer and staunch opponent of the death penalty, offered his services to the Scottsboro defense, the CP said that he would have to publicly repudiate the NAACP to participate. Darrow declined.

Despite this sectarianism, however, the CP's campaign--with its outspoken opposition to racism and a commitment to multiracial organizing--began to attract more and more supporters.

In April 1931, a rally that started with 200 mostly white communists gathered in Harlem swelled to over 3,000, most of them Black, in a protest against the legal lynching. In Harlem, the campaign for the Scottsboro Boys included important supporters from the arts and music, such as poet Langston Hughes and singer Billie Holiday. Solidarity protests were also organized by communists in other countries, including a July 1931 rally in Germany, where 150,000 workers turned out to hear Scottsboro mother Ada Wright.

A 1933 march in Washington, D.C., turned out 4,000 people who marched for more than six miles in the pouring rain. The night before, several thousand African Americans joined hundreds of white supporters at the Mount Carmel Baptist Church to hear Ruby Bates, the alleged victim of rape who now proclaimed the innocence of the nine youth. "They were framed up at the Scottsboro trial," Bates said, "not only by the boys and girls on the freight train, of which I was one, but by the bosses of the Southern counties."

As a result of the growing pressure, the U.S. Supreme Court ordered the death sentences indefinitely suspended, after the Alabama State Supreme Court upheld the conviction of seven defendants and set their execution date. The Supreme Court ultimately overturned the convictions, but ordered new trials to take place in the Alabama courts. More protests were organized in the lead-up to new trials in March 1933.

Then, Ruby Bates came out publicly to admit that the defendants never touched her and hadn't even talked to her on the train. She explained that police forced her to lie about the incident. The ILD toured Bates across the country in support of the Scottsboro Boys.

But the Alabama courts had no interest in the truth. In a fourth trial, the youths were still found guilty, but the sentences reduced to life in prison--in the fifth, four were found innocent. In 1950, the charges against all the Scottsboro Boys were finally dropped.

The defense campaign ultimately didn't win freedom for the Scottsboro Boys, but it saved them from the execution chamber--an outcome that was hard to imagine in the Jim Crow South of that era.

The years-long Scottsboro defense campaign provides important lessons on how to organize a multiracial movement that protests an individual racist attack--while linking it with the racism and inequality endemic to capitalism that must be confronted in the struggle for a different world.