Challenging the drug war lies

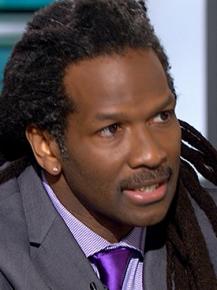

Neuroscientist Carl Hart takes on racist myths about drugs, writes .

DR. CARL HART'S book, High Price: A Neuroscientist's Journey of Self Discovery That Challenges Everything You Know About Drugs and Society, lives up to the claim made in its title.

With no apologies, Hart takes on the racist "war on drugs" and challenges the hysteria and junk science that is used to pressure politicians to pass draconian drug laws and turn the public against drug users and dealers.

As a researcher, Hart marshals the studies, including his own, and statistics to show that the majority of people who use drugs do not become addicted, not even to the so-called "hard" drugs like cocaine, heroin or methamphetamine. He shows through concrete examples that not all drug use is abuse, and that patterns of drug use change over time. "Knowing that someone uses a drug, even regularly, does not tell us that he or she is 'addicted,'" Hart writes. "It doesn't even mean that the person has a drug problem."

But what's really refreshing about this book is that Hart shows how drug use and addiction is created and maintained by environmental factors.

Hart's analysis is a conscious rejection of the idea, heavily promoted by Nora Volkow, director of the National Institute of Drug Abuse (and, incidentally, the great-granddaughter of Leon Trotsky), that addiction is a brain disease.

Volkow's theory is that drugs cause changes in brain structure that make it impossible for users to resist addiction. This denies the role that racism, poverty, unemployment, homelessness and trauma play in addiction. It lets the economic structures of oppression off the hook and locates the cause of addiction in the nucleus accumbens of individual brains.

IN CHALLENGING such ideas, some of Hart's observations come from his own background.

He grew up in a working-class neighborhood in Miami, with eight brothers and sisters. His father worked all week, and on weekends became violently drunk and beat his mother. When they divorced, the family was plunged into poverty, and depended on a myriad of government assistance programs to survive.

Hart proudly asserts that these programs kept his family from homelessness and hunger, and ultimately helped him to his current position as a tenured professor at Columbia University in New York City. In the acknowledgements, he thanks these government programs and bemoans that fact that many have been deformed or eliminated.

Hart experimented with drugs himself and at one point became a pot dealer, but he never became addicted to any drugs, despite having numerous risk factors. He believes his involvement in sports was crucial--he wasn't going to let drugs impair his ability to play football, so he kept his use to a minimum.

Music also played a part in Hart's youth. He became a DJ. He was a member of the Bionic DJs, who played a show with Run DMC before the group became famous. Hart credits music with giving him a positive outlet of expression and for meeting creative and committed artists--and women.

As a teenager, Hart details some close scrapes with the law and acknowledges in the chapter "Choices and Chances" that it was pure luck he was never imprisoned. He quotes several studies showing that "regardless of the severity of the initial offense, teens who were incarcerated were three times more likely to be re-incarcerated as adults compared with those not incarcerated for similar offenses." The drug war, of course, became the pretext for locking up generations of young Black men, branding them as felons and setting them up for recidivism.

Realizing that he had few employment opportunities in Florida, Hart enlisted in the Air Force. He was stationed first in Japan and then England. Living outside of the U.S. helped Hart develop critical viewpoints that his impoverished education had not. He immersed himself in the music and lyrics of Gil Scott-Heron and Bob Marley, and becomes increasingly politicized. He read Shakespeare and Langston Hughes and met white people who unequivocally supported civil rights and the equality of Black people in the U.S.

When Hart returned to his neighborhood in the late 1980s, the so-called "crack epidemic" was in full swing. His writing on the war on crack cocaine is the highlight of the book and is clear, concise and convincing. In the chapter "Home is Where the Hatred is," Hart explains:

The effect of crack, when it had one, was mainly to exacerbate the problems that I'd seen in my home and in the hood since the 1970s. It didn't create the world of hustlers, dealers and addicts celebrated by rappers or the underground economy that I'd always known. It was just a marketing innovation that added a new product to the drug world. The drug's pharmacology didn't produce excessive violence. However, whenever a new illicit source of profit is introduced, violence increases to define and retain sales territory.

Hart shows how the crack hysteria was so powerful, it convinced progressive Black Democrats to attack their own communities. In the book, he calls out Black leaders such as Rev. Jesse Jackson and Rep. Charles Rangel for embracing the rhetoric of "law and order" and "tough on crime" that so devastated the lives of hundreds of thousands of Black families.

AS HART progressed in his career as a neuroscientist, he studied the effects of nicotine, amphetamines and cocaine in humans. He became skeptical of much of the research he read, including the numerous, well-publicized studies showing that rats and even primates continually pressed levers to get cocaine, heroin or methamphetamine, until they died, choosing drugs over food or water. These studies were used to assert that humans, given unlimited access to crack, would act the same way.

Left out of the reporting on these studies was the fact that the lab rats were kept in isolated cages and unnatural environments that were incredibly stressful, because rats are social rodents.

Another study that didn't get nearly the same amount of media attention proved the opposite. The so-called "Rat Park" study examined if rewarding alternatives like social contact and sex would affect rat's choices about whether to take drugs. The researchers found when rats lived together in stimulating environments that closely resembled their natural habitat and could mate, they rarely chose to drink morphine-laced water. The rats that lived in isolation drank up to 20 times more morphine than the rats living in "the park."

The conclusion: Environment, social support and alternatives to drugs play a vital role in whether or not people develop addictions.

These studies had a profound effect on Hart. He began to confront the junk science with his own research. He conducted experiments with crack and methamphetamine users at New York-Presbyterian Hospital. Study participants were given pharmaceutically pure crack, and after 15 minutes, were offered another hit or $5. Participants consistently chose the money over crack.

Hart writes of his surprise: "Over and over, these drug users continued to defy conventional expectations...Not one of them crawled on the floor, picking up random white particles and trying to smoke them. Not one was ranting or raving. No one was begging for more, and absolutely none of the cocaine users ever became violent. I was getting similar results with methamphetamine users."

Beyond his questioning of junk science, Hart has consistently exposed the racism that is central to the war on drugs--and has called out drug policy reform organizations that avoid talking about racial disparities. In a recent Nation article, Hart took the marijuana reform movement to task for not putting racial justice at the center of the fight.

In his book, Hart admits that it took him some time to "distinguish between truth and the bullshit about drugs." But High Price is all truth and no bullshit.