Twenty years after the Zapatista uprising

The Zapatista uprising that began 20 years ago this month shook Mexico and gained renown and support around the world. In this revised and updated article originally written for the 10th anniversary of the rebellion, and look at the roots of the Zapatista uprising and its impact on politics in Mexico and internationally in the 20 years since.

AS MEXICO'S bosses toasted the New Year on January 1, 1994, more than 2,000 guerrillas were seizing four towns in the southern state of Chiapas. It was the beginning of an uprising that would become celebrated around the world.

Declaring their intention to march on Mexico City to overthrow the "bad government" and vowing to create "liberated areas" where the population would gain "the right to freely and democratically elect their own administrative authorities," the then-unknown Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN) punctured the Mexican ruling class' smugness.

The Zapatistas' manifesto claimed their "inalienable right" under the Mexican constitution "to alter or modify their form of government" and demanded that the government recognize them as a belligerent at war:

We are a product of 500 years of struggle: first against slavery, then during the War of Independence against Spain...then to avoid being absorbed by North American imperialism, then to promulgate our constitution and expel the French empire from our soil...Later the dictatorship of Porfirio Diaz denied us the just application of the Reform laws, and the people rebelled and leaders like Villa and Zapata emerged, poor men just like us.

The EZLN chose to make its statement on New Year's Day 20 years ago because that was the day that the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) went into effect.

For Mexico's rulers, membership in NAFTA represented the hope of solidifying a special--and profitable--relationship with Corporate America. But to the Indian peasants and farmers who supported the Zapatistas, NAFTA meant a "death certificate"--because it would undermine their own agricultural production, a guerrilla said in a radio interview.

Instead of celebrating the Mexican economy's entrance into the "first world," the government of then-President Carlos Salinas de Gortari unleashed a ferocious military assault on the civilian population of Chiapas. But within days, Salinas was forced to call off the assault, as hundreds of thousands of Mexicans flooded into the Zócalo, the central government square in Mexico City, to show their solidarity with the Zapatistas.

The Zapatista uprising revived a left in Mexico that had been dormant for years--and put a spotlight on the question of the rights of Mexico's 20 million indigenous people. For the international left, the rebellion represented the first major blow against the free-market triumphalism that reigned after the collapse of the ex-USSR in 1991. Over the next decade, the Zapatistas and their chief spokesperson, the highly quotable Subcommander Marcos, helped to popularize the left's developing critique of the free market agenda of corporate globalization, known as "neoliberalism."

Roots of the Uprising

For most observers, the rise of the EZLN was a surprise. The group emerged from self-defense brigades set up to protect peasants from the terrorism of Chiapas' coffee barons and cattle ranchers.

Peaceful land occupations turned bloody when the landlords' pistoleros (gunmen) attacked peasants. As Marcos said in one interview, over time, "the comrades saw it wasn't enough to do self-defense of a single community: but rather to establish alliances with others and to begin to take up military and paramilitary contingents on a larger scale."

If one single event can be said to have pushed these paramilitary groups to embark on the road of armed insurrection, it was the Salinas government's 1992 decision to repeal Article 27 from the federal constitution. Article 27, a product of the Mexican Revolution, guaranteed peasants the right to petition to use disused private land or land held by the state.

Since the revolution almost a century earlier, the quality of land distributed under Article 27 had worsened, with only about one-fifth of it considered arable. But ending Article 27 closed off any hope for peasants that they might be able to gain a plot of ground to call their own.

The government's repeal polarized indigenous communities and peasant organizations between those who supported continued "peaceful" methods of struggle and those who chose the "armed struggle." In the debates that broke out over how to respond to the government, the "armed struggle" tendency won out. Long before NAFTA was ratified by Congress in the U.S., the EZLN's leadership had set a date for an uprising.

The EZLN developed from the efforts of the Maoist organization Popular Politics (PP). Its chief theoretician, National Autonomous University professor Adolfo Berlinguer, argued that student radicals and intellectuals must live among the masses and organize them.

By one account, Samuel Ruiz, the Catholic archbishop of Chiapas and proponent of liberation theology, was so impressed with the PP's neighborhood organizing in Torreón that he invited PP activists to move to Chiapas. Subcommander Marcos said that he was one of the first 12 PP activists who relocated in Chiapas in 1983 to organize a guerrilla war.

The radicals operated under the protection of the church, often accompanying priests on religious missions into rural areas. They demanded "work, land, housing, food, health, education, independence, freedom, justice and peace" and pledged to form a "free and democratic government." While they appealed to Mexican nationalism, they also spoke on behalf of Mexico's oppressed indigenous population.

Struggle and Solidarity

The Chiapas uprising was the first major guerrilla challenge to the regime since the 1970s. Twice, the government attempted to suppress the EZLN militarily--once in January 1994 and another time in February 1995. Both times, the government was forced to retreat in the face of massive protests in Mexico City, the rest of the country and around the world.

In May 1994, the Zapatistas forced the government to meet with their leaders and offer the EZLN a series of reforms. These included general demands, from improved health care and sanitation to increased farm prices. The government also agreed to specific demands to address the needs of the region's indigenous population, such as support for indigenous language radio stations.

The EZLN, arguing that the government's offer was insufficient, rejected it in June 1994. Since then, as many as 25,000 troops have surrounded the Zapatistas in the hills of the Lacandón jungle--while the army conducts a "low-intensity" war against the population of Chiapas.

After a couple years of on-again, off-again negotiations, the EZLN thought it had reached an agreement with representatives of the government of President Ernesto Zedillo in 1996. This deal, known as the San Andrés Accords, establishes local autonomy for indigenous peoples in Mexico, as well as new educational, social and cultural rights. It requires changes to state, federal and local laws, and to the Mexican constitution, and it commits the Mexican government to eliminating "the poverty, the marginalization and insufficient political participation of millions of indigenous Mexicans."

However, after signing the accords, the Zedillo government reversed itself and refused to implement the agreement. Meanwhile, the army stepped up its "dirty war" against the civilian population of Chiapas in an attempt to undermine rebel support.

The most brutal incident occurred in December 1997, in the village of Acteal, where 45 civilians, including 36 women and children, were murdered by government-backed paramilitaries. The Acteal massacre resulted in the resignations of the government's interior minister and the governor of Chiapas, who was found to have advance knowledge of the killings.

The EZLN responded to the deadlock and the increased violence by trying to mobilize broader support from the Mexican public. In 1999, it organized a national consulta, or referendum, on the question of indigenous rights and the implementation of the San Andrés Accords. More than 3 million Mexicans participated in the consulta, 95 percent of them endorsing the EZLN's demands.

When he was running as the candidate of "change" in 2000, former Mexican President Vicente Fox of the right-wing opposition National Action Party (PAN) pledged to solve the deadlock with the Zapatistas in "15 minutes." Soon after taking power in December 2000, Fox committed himself to submitting the San Andrés Accords to a Congress where PAN wasn't the majority.

To build support for approval of the Accords, the Zapatistas and their supporters mounted a 16-day caravan, bringing Marcos and other EZLN comandantes from Chiapas to Mexico City in February and March 2001. At every stop along the way, enthusiastic crowds supporting the EZLN and the Accords greeted the caravan. As many as a quarter of a million rallied in the Zócalo in Mexico City in solidarity with the Zapatistas' demands. Yet Congress gutted the Accords, and the Zapatistas returned to Chiapas empty-handed.

With a few exceptions since then, the Zapatistas and Subcommander Marcos have remained largely aloof from major political developments. At one time, 38 pro-EZLN communities in Chiapas subsisted on support from U.S. and European non-governmental organizations.

Twenty Years of Conflict

In the two decades since the uprising, much of what the Zapatistas warned against has come to pass. Real wages of Mexican workers have fallen since 1994, while the economy's growth at 1.2 percent per year has been among the lowest in Latin America.

As many as 2 million Mexican farmers have been driven off their land, and the country now imports corn for tortillas. These terrible conditions brought thousands of farmers into the streets in 2004 and led the major unions to threaten a general strike against Fox's plan to increase taxes on working people's necessities. The protests culminated in the demonstrations that helped to sink the World Trade Organization summit meeting in Cancún that year.

The Zapatista uprising also helped to force open the Mexican political system. As a result, the longtime ruling party, the PRI, lost its first presidential election in seven decades in 2000. But in the years since, the right-wing PAN, followed by the return to government last year of the PRI, have continued to privatize and dismantle the state's minimal social provisions. Late last year, the PRI-dominated government voted to privatize the national oil company PEMEX.

While they weren't the only source of the global movement against free-market fundamentalism that swelled throughout the 1990s, the EZLN was certainly part of that struggle. Yet despite all this, the EZLN today remains isolated in the hills of Chiapas, unable to get the government to implement the San Andres accords. There's a clear sense that the Zapatistas have lost the political momentum that sustained them in the early years after their uprising.

When the Zapatistas launched their uprising, they pledged to march on Mexico City and called Mexicans to rise up "to depose the dictator" Salinas. But a few weeks into the uprising, EZLN leader Subcommander Marcos said the Zapatistas had no desire to "take power," nor to interfere with the elections planned for August 1994.

While widespread sympathy for the Zapatistas remains around the country, they are isolated from the majority of Mexicans, who are workers living in and around the country's urban areas.

The EZLN has made several attempts to establish a support network. It launched the Zapatista National Liberation Front (FZLN) to forge a link with "civil society" in 1995. Unfortunately, the lack of a clear focus and excessive deference to Marcos prevented the Front from growing outside the ranks of the existing left.

The Zapatistas have generally abstained from taking positions in national elections. While their denunciations of the mainstream parties for their corruption and their support of neoliberalism is commendable, their refusal to project their influence into the wider Mexican society and to build a political alternative has been one of their greatest weaknesses.

In 2006, the Zapatistas launched "the other campaign" of rallies against capitalism and racism, and for democracy, during the national presidential campaign. Their rallies drew tens of thousands, while the populist candidate Andrés Manuel López Obrador drew millions. But when the PAN and the right-wing media conspired to cheat López Obrador out of his likely victory, the Zapatistas withdrew to Chiapas, refusing to participate in mass mobilizations to defend the true winner of the election.

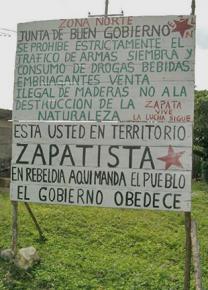

This type of abstention cost the Zapatistas much moral authority in the broader Mexican left and popular movement. They have instead concentrated on organizing autonomous communities, known as caracoles and the juntas de buen gobierno, in the deepest part of the Chiapas jungle.

A New Model for the Revolutionary Left?

Many Western radicals heralded the Zapatistas as examples of a new kind of left that "changes the world without taking power." Instead of seeking to challenge the power of the state at a national level, the Zapatistas were supposed to be leading by example in the far reaches of Chiapas.

But not only is very little known about how the EZLN actually operates the autonomous communities, the Zapatistas' decision to absent themselves from the broader national scene is also problematic, according to La Jornada columnist, the socialist Guillermo Almeyra, speaking to an interviewer:

They weren't able to weigh, in my opinion mistakenly, the policy of the EZLN to isolate [indigenous communities] from the national scene, from the struggle over oil [privatization], from the struggle for democracy, or from the international struggles of indigenous people, like those in Ecuador or Bolivia. This kept the indigenous people of Chiapas from having a broader perspective, and also deprived the rest of the Mexican population of a very important source of political support--those who'd resisted, arms in hand, in a small corner of Chiapas.

The Zapatista movement has raised many questions that challenge the priorities of the free market. An EZLN fighter interviewed during the first days of the rebellion was reported to have said that he was fighting for "socialism like Cuba, only better."

Still, the Zapatistas aren't socialists. On the contrary, they quite explicitly situate themselves in the Mexican revolutionary nationalist tradition of Zapata and Villa. Their "First Declaration of the Lacandón Jungle," issued on the eve of their uprising, cited the authority of the Mexican constitution to legitimize their insurrection. "We are patriots," they declared, "and our insurgent soldiers love and respect our tricolored flag."

But in Mexico today, the free enterprise system is responsible for holding millions of people in poverty and exploitation. Only the working class on both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border has the power to bring the system to its knees.

Defeating the forces of corporate globalization that are crushing Mexican workers, peasants and indigenous people will require not just rebellion, but a revolution that replaces a system based on profit and greed--with a society controlled by workers that will meet human needs.