I am an invisible man

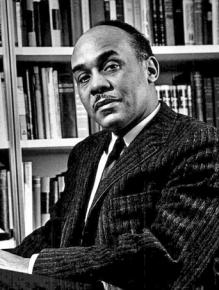

looks at the legacy of Ralph Ellison, author of the landmark Invisible Man.

UNTIL IT was deposed by Toni Morrison's Beloved, Ralph Ellison's Invisible Man was the queen of modern African American fiction. The book was published on April 14, 1952, when Ellison was 39 years old. It won the National Book Award of 1953, beating out John Steinbeck's East of Eden and The Old Man and the Sea written by Ellison's idol, Ernest Hemingway.

Since its publication, it has been a standard on American literature syllabi, and has never gone out of print. In 1998, the Modern Library ranked Invisible Man on its list of the 100 greatest novels in the English language of the 20th century.

Invisible Man is the Black Odyssey of a young African American man who travels from the American South to New York City in search of his identity and, at a deeper level, the meaning of race. The book's famous opening lines, echoing "Call me Ishmael" from Herman Melville's Moby Dick, are a brilliant riff on the spectrality of Black life in racist America:

I am an invisible man. No, I am not a spook like those who haunted Edgar Allan Poe; nor am I one of your Hollywood-movie ectoplasms. I am a man of substance, of flesh and bone, fiber and liquids--and I might even be said to possess a mind. I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me.

Ellison's novel blended high Anglo-modernism (references to James Joyce and T.S. Eliot); classical allusion, existential comedy, and long, deep grooves of Black culture. It begins and ends with the hero living under the streets of Harlem, eating ice cream and sloe gin, bootlegging electricity in order to spin Louis Armstrong's "What Did I Do to Be So Black and Blue," a double-entendre for the hero's life.

The novel's plot is a modern-day slave narrative told in flashback. Early on, the young, spindly narrator is forced to fistfight his Black peers at an all-white Southern smoker in order to win a scholarship to university. At college, a thinly veiled rendition of Ellison's alma mater, Washington's Tuskegee Institute, the narrator is expelled when he chauffeurs a rich white benefactor into the forbidden backwoods of the Black Southern peasantry.

He leaves, a refugee on a one-man migration. In New York, he becomes an accidental trickster, inhabiting a range of Black personas and personalities presented so that neither he nor the reader can easily distinguish them from stereotype: industrial worker, lover, orator, revolutionary.

In the end, his ambition, even to become someone, is defeated. The book concludes with Harlem in flames and the protagonist wondering: "What and how much had I lost by trying to do only what was expected of me instead of what I myself had wished to do?" The book's final line is as famous as its opening one: "Who knows but that, on the lower frequencies, I speak for you."

PUBLISHED BETWEEN Richard Wright's blockbuster protest novel Native Son in 1940, and James Baldwin's historic essay collection Notes of a Native Son in 1955, Invisible Man temporarily gave Ellison the whole stage of African American literature.

The novel especially endeared him to a white literary establishment that recognized Ellison's high-minded artistry as dedication to craft, form, irony and "complexity," elements that conservative New Critics and university professors were trying to install as standards of greatness for American literature.

Jewish American writers like Saul Bellow also recognized---partly through obvious symbolic associations in the book---that Ellison was trying to affirm a "democratic" impulse toward multiethnic diversity in the U.S., a cozy fit with Cold War liberalism's cultural and political war with Communism.

The affirmation by Ellison's narrator that "Diversity is the word. Let man keep his many parts and you'll have no tyrant states" seemed tailor-made to reinforce the idea of the U.S. as the land of the free.

But history can also be a trickster, too. 1952 was in many ways the high point of Ralph Ellison's life. While he lived, he never published another novel, despite a lifetime of trying. His two posthumously published novels were odd conglomerates of long, disjointed manuscripts, herded into shape by executors and editors.

Ellison spent much of the 1960s and 1970s as a self-imposed pariah to a rising tide of African American authors and political activists raised on his book, who sought his approval, attention and support as willfully as he rejected giving it to them.

For much of his life, he was the writer most famous in America for never reaching his potential. Beyond that, he was a surly, petty and reactionary grouch. His disappointments at the time of his death in 1994 were legion.

ELLISON WAS born in Oklahoma six years after it became a state. The title of his 1986 essay collection, Going to the Territory, commemorated both the ending of one of his favorite books, Huckleberry Finn, and his birthplace in a land once home to sovereign Native American tribes displaced by white settlers, and where, by 1900, nearly 60,000 African Americans had settled to claim 100-acre parcels of government-distributed land.

Ellison grew up working class and poor, raised by his progressive mother, Ida, a domestic. He was so broke that he rode the rails, hobo-style, to Tuskegee to begin classes. He studied music in school and played the cornet; he later wrote brilliant essays on jazz and blues, and idolized Duke Ellington, though his neoclassical temperament downgraded beboppers like Charlie Parker and later Miles Davis.

Ellison left Tuskegee without a degree and headed for New York City, convinced he wanted to be an artist. His early literary influences were European and Russian classics--Dostoevsky's Crime and Punishment, Emily Brontë's Wuthering Heights and Thomas Hardy's Jude the Obscure.

Things changed when he met Langston Hughes in Harlem. Hughes introduced Ellison to literary radicalism and real Communists like Louise Patterson not long after the two of them had returned from a filmmaking expedition to the Soviet Union. A few years later, Ellison was remade completely when he met Richard Wright.

Wright had moved to New York from Chicago, where he had joined the Communist Party and written several of the stories for his 1938 book Uncle Tom's Children in the Chicago John Reed Club. In Harlem, Wright alternated writing articles for the Daily Worker with work on his novel Native Son.

Ellison was mentored in Marxism by Wright. Wright also encouraged Ellison to write his first short story and helped him place his first book review in New Masses, the Communist Party's cultural journal.

From 1938 until about 1944, Ellison was a Stalinist. He defended the Moscow purges and the Stalin-Hitler pact. He also thought that Bigger Thomas, the lumpenproletariat hero of Richard Wright's Native Son, was a brilliant revolutionary provocateur.

Thomas's deep alienation winds up in him killing, and equating his crimes with his emancipation. "Would that all Negroes were as psychologically free as Bigger and as capable of positive action!" Ellison wrote. Ellison looked directly past the violence against women in Native Son that later generated groundbreaking Black feminist criticism; this blindness went hand in hand with casual locker-room misogyny expressed in his letters to Wright.

Ellison's relationship to Marxism and communism also produced what is the most important and lasting legacy of Invisible Man. Midway through the novel, the protagonist is recruited to a radical organization called "The Brotherhood" when he gives a brilliant improvised speech protesting the forced eviction of some Harlem residents.

The Brotherhood is Ellison's unsubtle caricature of the American Communist Party. Its figurehead is a white man known as "Brother Jack," who patronizes the protagonist and "disciplines" him so that his native intelligence is straitjacketed to the party line. White male Brotherhood members are manipulative, paternalistic and racist; white female comrades want to bed the protagonist as their "stud."

In the end, the Brotherhood is blamed for instigating a riot that burns down Harlem and for the death of Tod Clifton, a Harlem youth organizer. These events send the Invisible Man into his final political hibernation and disillusionment.

WHEN IT was published and for years after, Ellison's portrait of the Brotherhood and its manipulations of the Invisible Man became consensus metaphors in literary criticism and university classrooms for communist duplicity and the exploitation of African Americans.

Ellison himself disavowed any close relationship to Marxism or communism, refused to republish his New Masses writings, and generally served as a mouthpiece for the virtues of American liberalism and democracy during the Cold War.

Yet Arnold Rampersad's 2007 biography of Ellison and Barbara Foley's 2010 book Wrestling with the Left: The Making of Ralph Ellison's Invisible Man complicated things. Both books showed that Ellison's hostile portrait of the Brotherhood resulted in part from his disgust with the Communist Party's embrace of a "people's war" after the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union ,when it subordinated the fight against racism and the class struggle (for example, the CP supported a no-strike pledge during the war) to the "united front" fight against fascism.

Ellison felt the shift in line was a betrayal of Black workers. Rampersad and Foley overturned an important consensus on the politics of the novel by showing that Ellison's criticism of the CP came, initially, from the left, not the right

Why does this matter? Because for years, critics of Invisible Man masked or ignored Ellison's Stalinism, his later criticism of Stalinism and the Stalinization of the American Communist Party in order to create their own caricature of "communism" they could discard to the dustbin of history.

Ellison's novel also was used to argue, especially during the "pre-African American Studies" days of the 1950s and 1960s, that Black writers were deeply suspicious of ideas from the left that threatened their comfortable assimilation. This helped to bury a long history of African American writers in the 1920s and 1930s who had been members of the Communist Party or sympathetic to it.

Ironically, Foley shows in her study that Ellison's early short stories and preliminary drafts of Invisible Man were heavily shaped by his admiration for proletarian literature and Marx's analysis of class society. Foley demonstrates that Ellison not only caricatured the Communist Party in his final draft of the novel, but expunged a much more "radical," even revolutionary narrative of Black working-class consciousness and rebellion.

As to whether Ellison ever joined the Communist Party, the record is unclear, though Foley discovered in Ellison's papers a "Branch Control Record" that suggests at the very least a close relationship.

Ellison spent much of his life after publication of Invisible Man grooming his image to conform to what Cold Warrior Arthur Schlesinger called the "vital center" of American life. He lived on royalties, guest lectureships and expensive speaking engagements at places like Harvard, Princeton and Bard College.

He hobnobbed with establishment white writers and politicians, and courted appointments and awards from mainstream academic and intellectual societies. His politics became more elitist and moved further to the right. He criticized James Baldwin for writing openly about his homosexuality: "Perhaps what Baldwin is telling white Americans is: Allow Negroes to sleep with your daughter, or we homos will sleep with you."

He showed no interest in supporting African decolonization movements during the 1950s, even when asked to do so by friendly peers like Langston Hughes. During the 1960s, he sneered at the Black Arts Movement and Black Nationalism, defended the U.S. war in Vietnam and opposed the development of Black Studies programs. He was mildly critical of the Reagan administration's reduction of federal funding for education and social services in the 1980s, but never used his reputation to speak forcefully for African American equality.

ONE OF Ellison's few captivating moments as a writer after Invisible Man was a 1964 essay duel with Irving Howe, of Democratic Socialists of America. In his magazine Dissent, Howe published an essay titled "Black Boys and Native Sons," taking Ellison and Invisible Man to task for their obvious anti-communism, but also prescribing that African American writers had an inherent responsibility to protest social inequality.

Ellison responded with an essay titled "The World and the Jug." In it, he defended both the universality of art and the right of African Americans to create as they pleased, according to the complexity of Black life. Ellison basically called out Howe as an essentialist and won the debate. But his high-minded claims for "universality" and the complexity of Black life and art were rarely applied to anyone's work but his own.

Ellison died of pancreatic cancer in 1994 in New York City. Since his death, three works of his fiction have been published: Flying Home and Other Stories, which includes many brilliant, early pieces; Ellison's unfinished second novel Three Days Before the Shooting; and Juneteenth. Ellison's jazz writings and essays have also been published in book form.

Unfortunately, none of his posthumous body of work has done much to offset disappointment at how little Ellison produced over the course of a long life. It's certain that his full legacy as a writer will take more time to sort out. In the meantime, Toni Morrison's assessment of his life and work seems worthy of the last word:

...one is tempted to say...that it is tinged with tragedy, because expectations of much more fictional work were never realized. But tragedy is not the right word; it requires grandeur. The better word is melancholy. One contrasts the largeness of Invisible Man with its broad canvas and its wide range of effects, of insight, with the narrowness of his public encounters with Blacks. The contemporary world of late 20th century African Americans was largely inaccessible, or simply uninteresting to him as a creator of fiction. For him, in essence, the eye, the gaze of the beholder remained white. But if the ideal white reader made sense for Invisible Man in 1952, he or she made less sense for the Black writer by the seventies and eighties. And I don't think Ellison ever saw the need to revisit or redress anything he had done or not done, or to challenge his obvious level of success with more demanding ones. He saw himself as a Black literary patrician, but at some level this was a delusion. It was simply his solution to that persistent problem Black writers are confronted with: art and, or versus, identity. I don't see tragedy in his predicament. I see a kind of sadness instead.