Seeing through the chairman’s new clothes

looks back at the work of pioneering and idiosyncratic writer Pierre Ryckmans, in an article written for Revolutionary Socialism in the 21st Century.

IT'S NOW generally accepted that the Cultural Revolution was a disaster for China, one of the most traumatic periods in the nation's recent history. But at the time, the view was very different. It was variously seen as part of the worldwide youth rebellion of the 1960s, as a giant experiment in direct democracy, and as a means of refreshing the 1949 revolution and keeping bureaucracy at bay.

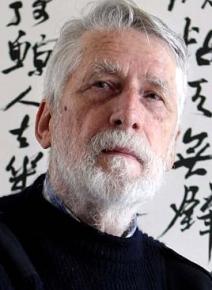

Pierre Ryckmans, who died earlier this month aged 78, was one of the very few authors to see through this at the time. Writing under the pen name Simon Leys, he published first The Chairman's New Clothes in 1971 and then Chinese Shadows in 1974--both long out of print, but to be snapped up if you ever see them second-hand.

The Chairman's New Clothes is one of the few books written at the time that is still worth reading today. He announced his intentions in the book's opening paragraph:

The "Cultural Revolution" had nothing revolutionary about it except the name, and nothing cultural about it except the initial pretext. It was a power struggle waged at the top between a handful of men and behind the smokescreen of a fictitious mass movement. As things turned out, the disorder unleashed by this power struggle created a genuinely revolutionary mass current, which developed spontaneously at the grassroots, in the form of army mutinies and workers' strikes on a vast scale. These had not been prescribed in the program, and they were crushed pitilessly.

The bulk of the book is a diary, written from 1967 to 1969, which drew on the official Chinese press to show how the movement was throughout manipulated from the top, and how from 1968 onwards, Mao was working to rein in his previous allies in order to keep the Communist Party and state from falling apart. Much more is now known about the Cultural Revolution, but plenty of what we have learned since the fall of Maoism has vindicated Ryckmans' basic thesis.

Chinese Shadows, written when he was living in Beijing as a Belgian diplomat, is probably his best book, and certainly the most accessible. Ryckmans had a deep knowledge of and sympathy for Chinese culture, but also an instinctive sympathy with ordinary people. When he laments the destruction of traditional culture, it's because everyday life is being impoverished.

And he has a lovely satirical style. The chapter on bureaucrats alone is worth whatever you pay for a copy. He notes of the army:

External insignia have nearly completely disappeared...They have been replaced by a loose jacket with four pockets for officers, two pockets for privates. In this way, a colonel travelling first class on the railway is now merely a four-pocket military man "sleeping soft"--with a two-pocket man respectfully carrying his suitcase. In cities, one can still distinguish between four-pocket men in jeeps, four-pocket men in black limousines with curtains, and four-pocket men who have black limousines with curtains and a jeep in front.

These books were followed by Broken Images and The Burning Forest, two collections of essays on various aspects of Chinese culture and politics. Many of these are now included in a new collection of essays published last year, The Hall of Uselessness--the only Simon Leys book still in print.

A FERVENT Catholic art historian with a fondness for anarchism, Ryckmans didn't fit neatly into any political category. Much of his critique of Maoism is rooted in a moral disgust about the use of radical language to excuse a new dictatorship. But he wasn't seeking to do anything more than open people's eyes to the grubby realities.

He was often denounced as a "reactionary," yet there isn't a word of sympathy for pre-1949 China in any of his writings. If he had a political hero, it was probably the iconoclastic Chinese author and journalist Lu Xun (1881-1936). One recurring theme of his writing was reclaiming Lu Xun's rebellious spirit from Maoists "who tried to annex him posthumously to their camp by means of various falsifications."

A couple of years ago, in a letter to the New York Review of Books about Spain 1936, Ryckmans quoted George Orwell: "The real division is not between conservatives and revolutionaries, but between authoritarians and libertarians." That's probably as close as he came to ever summing up his own political philosophy, and it served him well in cutting through the fog of bullshit that pervaded Maoism's declining years in the 1970s.

Ryckmans wrote very little on China after Mao, but was apparently not persuaded that anything fundamental had changed--his target was the system, rather than this or that individual or any particular aspect of bureaucracy. But his work remains well worth reading, not just for his defiance of what was then the accepted wisdom, but also the hope that he clung on to against what seemed like overwhelming odds. As he wrote in Chinese Shadows:

The pessimism that emanates from this book derives precisely from the essential unreality of its subject. But let this not deceive the reader: there is also a young, revolutionary China, repeatedly suppressed yet constantly struggling. Though invisible to us most of the time, it periodically bursts into the open with stupendous courage...On this "real" China we found our hope: the future belongs to it.

First published at Revolutionary Socialism in the 21st Century.