Ebola and the epidemic of fear

reports on the media frenzy over the first Ebola patient diagnosed in the U.S.--and asks why a disease discovered in 1976 doesn't have an effective treatment.

ONE WEEK after the diagnosis of the first case of the Ebola virus in the U.S., it's clear that racism and scaremongering have spread infinitely faster and wider in the U.S. than the disease, which has not struck a second person as of this writing.

The popular concern about Ebola is understandable given its frightening symptoms and lethal outcomes in West Africa, where thousands of people are infected. But that only makes the sensationalized frenzy of the cable news networks even more appalling, as they peddle lies and fear about the risk to anyone in the city of Dallas, where Thomas Duncan, the patient in question, was staying.

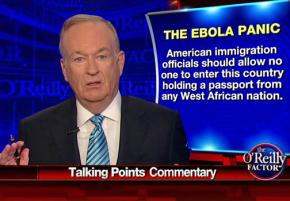

And they don't stop with Dallas, either. Right-wingers speculated about how supposedly lax U.S. border security could be putting us all at risk. "We have a border that is so porous, Ebola or ISIS--or Ebola on the backs of ISIS--could come through our border," Fox News' Greg Gutfield hyperventilated, as a red "Alert" logo flashed on screen.

Proposals for "tough action" were equally frantic: Halt all flights to and from Western Africa! Don't let anyone with a passport from a Western African country into the U.S.! Build a "double fence, triple fence, whatever it takes!" according windbag Charles Krauthammer, captured in The Daily Show's brilliant montage of the right-wing freak show.

Of course, Ebola can't be fought with greater militarization--in the U.S. or anywhere else.

If U.S. political leaders really wanted to stop Ebola from becoming a threat in the U.S.--not to mention confront a massive humanitarian crisis in Africa--the first place to start would be a massive influx of no-strings-attached medical and monetary aid to Western African countries. The World Health Organization estimates that at least $1 billion is needed.

Yet the Obama administration has so far focused on sending thousands of U.S. troops to Africa. They not only won't provide the kind of help needed, but would actually exacerbate the epidemic in places where U.S. military "protection" is viewed with suspicion, to say the least--and with good reason.

EBOLA HAS already killed some 3,000 people in Western Africa, with at least that many already infected--and those estimates are likely low. The worst-case scenario, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control, is as many as 1.4 million infected in West Africa by the start of the new year.

The World Health Organization has called the outbreak "unparalleled in modern times." Fatality rates for the disease are estimated at as high as 70 percent. In late September, Sierra Leone placed around one-third of its population--2.2 million people--under quarantine after house-to-house searches discovered hundreds of new cases.

This huge toll isn't because Ebola is easily transmitted--on the contrary, the virus is passed only through direct contact with the body fluids of an infected individual.

The rate of transmission in places like Sierra Leone, Liberia and Guinea has far more to do with poverty and resource extraction, overcrowding in urban slums, lack of public education and public health programs, and poor access to health care and health care resources--including protective equipment for medical personnel and the kinds of medical facilities that could isolate and care for those who are infected.

In the U.S., Thomas Duncan is reportedly in critical condition, and health officials are closely monitoring the 10 people who were in closest contact with him--though there's no indication yet that any contracted the disease.

As frightening as the threat of an Ebola epidemic might be, the grim truth is that Americans are far more likely to die from heart disease (600,000 deaths a year) or the flu (usually thousands, and sometimes tens of thousands, of deaths a year) than Ebola. And women in Texas have more to worry about from the fact that a majority of the state's abortion clinics were just closed when a federal appeals court upheld a right-wing law.

Yet the response of the right is scapegoating--epitomized by the report that Duncan, a Liberian citizen who travelled to the U.S. on September 20, is reportedly facing potential criminal charges from Dallas prosecutors, including "aggravated assault." "We are looking into whether or not [the man] knowingly and intentionally exposed the public to a deadly virus, making this a criminal matter for Dallas County," said DA's office spokesperson Debbie Denmon in an e-mail to Dallas station WFAA.

That's if Duncan survives, of course.

Dallas County District Attorney Craig Watkins says it would be "irresponsible" not to look into charges. But charging patients carrying infectious diseases with a crime is what's "irresponsible."

Criminalization, according to Bonnie Castillo, a nurse and director of National Nurses United's Registered Nurse Response Network, is "exactly the wrong approach and will do nothing to stop Ebola or any other pandemic." On the contrary, threatening people with arrest for the "crime" of getting sick will scare them away from seeking medical care.

Liberian officials have also announced that they plan on prosecuting Duncan, claiming he lied on an airport screening form about having come in contact with someone affected by Ebola. But this decision likely has less to do with believing Duncan knowingly exposed others to infection and more to do with the Liberian government's attempt to preserve links to the U.S. and other Western nations.

Duncan reportedly contracted Ebola after helping carry a pregnant woman who was infected from a taxi to a hospital--though it's not clear if he or anyone else knew at the time that the woman was sick with Ebola.

After traveling to the U.S., Duncan went to Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital on September 25 and acknowledged he had been in Liberia--yet was sent home with antibiotics.

Duncan's nephew Josephus Weeks had to personally call the Centers for Disease Control after his uncle was released from the hospital, out of fear that he wasn't given the appropriate care and that others would "get infected if he wasn't taken care of," Weeks told NBC News.

THE FIRST case of Ebola in the U.S. has exposed some of the failures of the U.S. health care system to respond to such crises, even on a small scale.

According to public health officials, because of the for-profit system in place in the U.S., preparations for a wide-scale health crisis like an epidemic are woefully inadequate. In a survey of nurses from more than 250 hospitals in 31 states, National Nurses United found that:

-- 80 percent say their hospital has not communicated to them any policy regarding potential admission of patients infected by Ebola;

87 percent say their hospital has not provided education on Ebola with the ability for the nurses to interact and ask questions;

One-third say their hospital has insufficient supplies of eye protection (face shields or side shields with goggles) and fluid resistant/impermeable gowns;

Nearly 40 percent say their hospital does not have plans to equip isolation rooms with plastic-covered mattresses and pillows, and discard all linens after use;

More than 60 percent say their hospital fails to reduce their number of patients to accommodate caring for someone who must be kept in "isolation."

"What our surveys show is a reminder that we do not have a national health care system, but a fragmented collection of private health care companies, each with their own way of responding," said Bonnie Castillo.

In general, America's for-profit health care system has an in-built disincentive to seek immediate treatment. Undocumented immigrants, for example, fear the repercussions if they go to a health care facility--and people in low-wage service sector jobs without health insurance or sick leave typically put off seeking treatment because of the cost. With infectious diseases, especially one as serious as Ebola, every day of further exposure in the community increases the risk that the disease will spread.

And it's not just the health care system. On October 2, cleanup at Duncan's apartment complex was halted temporarily when crews contracted to remove any potentially hazardous materials from the apartment couldn't work--because the company didn't have permission to transport hazardous material by road.

That left the people Duncan had been staying with essentially trapped inside the apartment, along with towels, sheets and other materials that Duncan may have used--and under threat of criminal prosecution if they left. (They have since been relocated.)

CAPITALISM ITSELF allowed this latest outbreak of Ebola to flourish--not only through the systematic extraction of resources and profit from Africa, resulting in high levels of poverty and the kinds of conditions that promote transition of the disease, but in a more direct way.

Outbreaks of Ebola first appeared in 1976--yet nearly four decades later, there is still no vaccine nor widely available drug for treatment. As the BBC reported in 2012, "Scientists say their understanding of the nature of the virus has markedly improved over the past decade. But the chances of turning that knowledge into a vaccine are very dependent on money."

During this outbreak, one promising experimental drug, known as zMapp, has been given to a handful of Western patients--but zMapp was already in short supply and remains unavailable for Africans.

The company that produces zMapp, Mapp Biopharmaceutical, was actually founded in 2003 "to develop novel pharmaceuticals for the prevention and treatment of infectious diseases, focusing on unmet needs in global health and biodefense." zMapp was reportedly developed in coordination with the Defense Threat Reduction Agency--a little-known arm of the Pentagon responsible for countering weapons of mass destruction.

In other words, this promising treatment for Ebola wasn't developed with saving the lives of those most affected by the disease in mind, but as a potential defense against germ warfare.

Back in 2012, Larry Zeitlin, president of Mapp Biopharmacueticals, told the BBC that the "commercial potential" of any Ebola drug therapy was limited. "I think it's unlikely that a large pharmaceutical company would get involved," he said. "There isn't a huge customer base, and Big Pharma is obviously interested in big profits. So these niche products which are important for biodefense are really driven by small companies."

LIKEWISE, A vaccine for Ebola has yet to be developed--in part because there is little profit to be made in creating one. In October 2012, two of the leading companies working on the creation of an Ebola vaccine--Sarepta and Tekmira--had funding terminated by the Pentagon because of "funding constraints."

The language that Sarepta's president used in discussing this funding cutoff was telling, however. Rather than decry the loss of a vaccine that could save thousands of lives, President and CEO Chris Garabedian spun the decision as a loss for the U.S. military: "It is unfortunate that [the Department of Defense's] near-term programmatic and funding issues may hinder their ability to reap the long-term strategic and economic benefits of using a single, common platform to address multiple threats."

As the Wall Street Journal summarized, "[F]or the scourges which affect predominantly the world's poorest people, including schistosomiasis and Chagas disease, making a profitable drug just doesn't look like an option."

Research and development funding for some diseases, including Ebola, malaria, dengue and tuberculosis, did rise some between 2008 and 2012, the Journal reported--but not out of any sudden sense of altruism:

Rising wealth in countries like China, Brazil and Indonesia should create a larger pool of payers, including governments, insurers and individuals, willing to finance treatments and preventative vaccines, experts believe.

Deutsche Bank health-care analyst Mark Clark calls drug companies' increased focus on tropical diseases a mix of social responsibility and "strategic investment in the customers of tomorrow, given that the tropics are home to over 40 percent of the world's population."

Vaccines in emerging markets--where a number of the largest drug companies are expanding--represent a [$9 billion] market that is growing around 11 percent annually.

There are other ways capitalism has been a culprit in hindering potential treatments in the current Ebola outbreak.

Science magazine reports that hundreds of doses of an experimental vaccine have been stuck in Canada rather than being shipped out for human trials as a result of an intellectual property dispute. Researchers accuse NewLink Genetics, a small company in Ames, Iowa, which bought a license to the vaccine's commercialization from the Canadian government, of "dragging its feet the past two months because it is worried about losing control over the development of the vaccine."

In an article titled "When Ebola comes to the U.S., who stands to profit?" the Washington Post pointed out that when the CDC announced the first U.S. case of Ebola last week, "The market reacted accordingly...The most striking monetary effect of the CDC's announcement was encapsulated in this headline from USA Today: 'Ebola stocks soar after infection hits U.S.'"

When greed is the first response to an epidemic that's already costing thousands of lives, with the threat of much, much worse to come, it's time to ask whether there's a better way to organize society.