Will there be justice for Eric Garner?

While the impact of the grand jury decision not to indict Darren Wilson is still reverberating--and stoking bitter protest--around the U.S., New York City is awaiting the decision of another grand jury deliberating on the fate of another police officer: the New York City cop who killed Eric Garner with an illegal chokehold this summer. New York City activist and WBAI radio co-host looks at the facts in yet another case of police murder.

IN NEW York City, like in Ferguson, African Americans aren't safe walking down the street.

Eric Garner was strangled to death by Patrolman Daniel Pantaleo in broad daylight on Staten Island on July 17. His killing might have gone almost unnoticed if a friend hadn't videotaped it--only to be arrested in retaliation for recording a police murder.

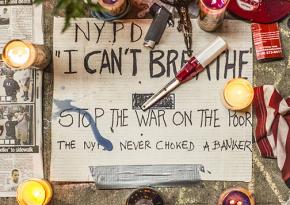

On the tape, Pantaleo can be seen holding Eric Garner in an illegal chokehold as he wrestles him to the ground. Garner can be heard crying out, "I can't breathe." The video shows Pantaleo pushing Garner's face into the sidewalk. Garner died a few minutes later--but police waited seven minutes before trying to resuscitate him.

The waiting game that preceded the grand jury decision in Ferguson, Missouri, over the death of Mike Brown is being repeated here--a Staten Island grand jury is reportedly in the final stages of deliberations on whether to indict Pantaleo. Rev. Al Sharpton has announced a "countdown" to the decision, saying, "I want to people to know that it's not just Ferguson--it's right here, and we're going to watch this grand jury."

New York City Medical Examiner Barbara Sampson has ruled the Garner's death was a homicide. She found that it was the chokehold, not some pre-existing condition like asthma, that killed him.

Eric Garner's "crime" was underselling local merchants by selling "loosies"--single, untaxed cigarettes--on the street for 50 cents apiece. Cops routinely hassled Garner. He was out on bail for selling untaxed cigarettes the day they killed him.

When the cops came after him, Garner threw his arms in the air and yelled, "I was just minding my own business. Every time you see me, you want to mess with me. I'm tired of it. It stops today."

ERIC GARNER wasn't killed in a city with a conservative political establishment and nearly all-white police force. New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio may be the most liberal big city mayor in the country. Unlike Ferguson, the New York City Police Department is 16 percent Black, and the First Deputy Commissioner is African American.

Still, the 'liberal" De Blasio anointed Bill Bratton as police commissioner even before he took office. And when he chose Bratton, de Blasio knew exactly what to expect.

Bratton already had a history with the NYPD. The first time he was police commissioner, under former Mayor Rudolph Guiliani, Amnesty International reported "a serious problem of police brutality and excessive force." Amnesty found that "racial disparities appear to be most marked in cases involving deaths in custody and questionable shootings." Researchers found a 34.8 percent increase in civilians shot dead by New York police and a 53.3 percent increase in the number of people who died in police custody with Bratton in charge.

Bratton is the champion of the "broken windows" theory of policing. He claims that the police can reduce violent crimes like murder, rape and mugging by rounding up masses of people for minor violations of the law known as quality-of-life offenses.

But broken windows policing doesn't actually reduce crime. Bratton likes to talk about how serious crime went down after he brought his broken windows program to New York City and Los Angeles. He doesn't mention that crime rates were going down nationally. In fact, it has declined as much or more in cities that haven't turned to broken windows policing.

Under Bratton, every New York City cop--from patrolman to precinct captain--is evaluated under a strict monthly quota system. Those who don't make the quota for misdemeanor arrests and summonses face immediate retaliation--anything from patrolling alone on foot to being fired.

The result has been an epidemic of petty arrests for everything from drinking a beer on a stoop to jaywalking, smoking a joint or fare-beating. For Eric Garner, it was selling untaxed cigarettes.

Inevitably, some of these stops and arrests escalate into confrontation and death, given the murderous record of New York police. Amadou Diallo was reaching for his wallet when cops shot him 41 times. Sean Bell was sitting in his car after his bachelor party. Anthony Baez threw a football that hit a cop's car and was killed for it. The list goes on and on.

Black men get killed in these confrontations because that's the way the system is designed to work. Stockbrokers may use coke, but there will never be a drug sweep on Wall Street. You might be able to get away with smoking a joint on the elite Colombia University campus, but don't try it at a New York public high school.

Officer Pedro Serrano recorded an inspector in the Bronx telling him exactly who police should target and where. On the recording, which was played in federal court, the inspector can be heard saying the cops should go after "the right people at the right time in the right location."

In case there was any misunderstanding, he added, "The problem was what? Male Blacks. And I told you that at roll call, and I have no problem telling you this: male Blacks, 14 to 20."

When cops get this kind of explicit instructions, the only wonder is that more African Americans and Latinos don't die on the streets. The problem isn't a few "rogue cops," but a whole system of policing.

Under capitalism, the police defend order and property, not people. But that doesn't mean that the people can't fight back against police harassment and brutality. Anything that moves power away from police headquarters and to the community can only make things better on the streets. If there can be community control of education, why not community control of policing? Why shouldn't elected precinct councils hire the precinct commander?

For now, the people of New York City need send a message: Bratton has to go--and take his broken windows with him, the sooner the better.