Bill de Blasio’s broken logic

The support for “Broken Windows” policing from New York City’s new mayor shows just how far liberals have moved to the right, writes .

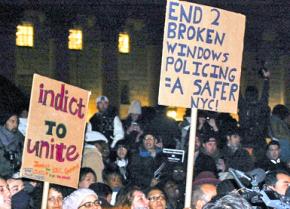

NEW YORK City Mayor Bill de Blasio proclaims himself to be a fighter against inequality, but this claim is undermined by his staunch support for the "Broken Windows" policing strategy that is all about brutally enforcing inequality.

Broken Windows criminalizes a host of so-called "quality-of-life offenses," such as panhandling or vandalism, which are said to create neighborhood conditions that lead to theft and violent crime. In practice, the policy has meant heightened police targeting of communities of color, which in turn has meant spikes in police violence, particularly against young Black men.

When Bill Bratton implemented Broken Windows during his first tenure as New York City police chief under Mayor Rudolph Giuliani in the 1990s, "disturbing allegations of mistreatment, police brutality, deaths in custody and unjustified shootings became so serious...that Amnesty International sent a team from London to investigate," according to Parents and Families Against Police Brutality.

But after running a campaign that emphasized his opposition to the police practice of "stop-and-frisk," de Blasio hired Bratton to be NYPD commissioner once more, declaring, "I believe fundamentally in the Broken Windows theory."

The results were predictable. Six months into the de Blasio administration, the New York Daily News found that "minorities were overwhelmingly targeted for quality-of-life summonses...81 percent of the 7.3 million people hit with violations for petty crimes between 2001 and 2013 were Black or Hispanic males."

The Daily News investigation came in the wake of the police murder of Eric Garner, who was choked to death by police pursuing the "quality of life offense" of loitering. Yet even then, de Blasio reiterated his support for the policy that led to Garner's death.

"Mayor de Blasio believes a number of the policing innovations created by the NYPD over the past two decades," declared a City Hall spokesperson. "including...a focus on quality-of-life offenses, have contributed to New York City becoming the safest big city in the nation."

But it is becoming clear that Broken Windows policing is making New York City particularly unsafe for Eric Garner and millions of other people of color.

Even after the recently ended NYPD slowdown offered considerable evidence that serious crime does not skyrocket once police stop targeting "quality-of-life" violations, de Blasio continued to voice support for this increasingly discredited policy.

Bill de Blasio is widely seen as a national leader of the Democratic Party's left wing. It is a sign of how far to the right the Democrats have moved over the past generation that this liberal favorite is holding tightly to a policy developed by Reagan-era conservatives and implemented under Rudy Giuliani.

DE BLASIO'S commitment to Broken Windows contrasts with an earlier generation of liberals, who were pushed by the civil rights movement to focus on "root causes" of unrest and crime.

Programs like Lyndon Johnson's War on Poverty dedicated billions of dollars of federal funding for jobs, housing and welfare programs. Ongoing protests--coupled with riots in numerous U.S. cities from 1964 to 1968--forced Johnson's Kerner Commission to conclude that "our nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white--separate and unequal."

As protest movements faded in the 1970s and '80s, the Reagan administration shifted state intervention to a war on crime--with crime increasingly defined at the individual level. Thus, the "war on drugs" was waged less against trafficking syndicates than against millions of low-level dealers and users who were ensnared in the criminal justice system.

The Broken Windows theory, conceived at the same time as the war on drugs, was an innovation designed to maintain order while preserving community relations. The Police Foundation, founded with a $30 million grant from the Ford Foundation, was one organization formed during this period to rationalize policing.

In the late 1970s, the Police Foundation commissioned George Kelling to make a series of studies on various strategies for policing communities. The results of those studies would be published in 1982, in an article co-authored with conservative theorist James Wilson, spelling out the Broken Windows theory.

Like the war on drugs, Broken Windows pointed the finger at individuals at the lowest conceivable level of "criminal behavior." Violent or serious crime was blamed on panhandling or loitering. As the original article argued, "one unrepaired broken window is a signal that no one cares, and so breaking more windows costs nothing."

Broken Windows reflected the conservative era in which it was devised. Its argument that petty behaviors cause crime totally ignores the role of poverty. By disregarding larger factors, the theory sidestepped conversations about social conditions and instead focused attention on individual behavior. For the next decade, writes Christain Parenti in Lockdown America, "the Broken Windows theory gestated on the right-wing margins of urban policy debates."

Instead of challenging these fundamentally conservative positions, Democrats emulated them. As the presidential nominee in 1984, Walter Mondale tried to out-tough Ronald Reagan by promising to deploy the U.S. military to win the war on drugs.

A decade later, Bill Clinton signed the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act--written by then-Sen. Joe Biden--which would fund 100,000 new police officers nationally, spend $9.7 billion to fund prisons, expand the death penalty, and eliminate federal grant money for inmate education.

This funding from Clinton and Biden would undergird Bratton's implementation of Broken Windows in New York City as the first major street test of the theory. With crime rates dropping across the country (and the world), Broken Windows was introduced at the perfect time so that its champions could take the credit for an innovative and effective new approach to policing.

With the debate on crime resolved in favor of whoever could be toughest on "criminals," the right was emboldened to push farther. In a 1995 budget briefing, Rudolph Giuliani was asked if the new aggressive policing associated with the introduction of Broken Windows was, in fact, an unspoken strategy to "clean up the city" by simply pushing out the poor. "That's not an unspoken strategy," Guiliani replied candidly. "That's the strategy."

BROKEN WINDOWS, the war on drugs and many new policing initiatives of the past two decades would be impossible without a more organized, militarized police force. This required a significant and deliberate shift beginning in the 1970s, which outfits like the Police Foundation played an important part in engineering.

As social movements grew in the 1960s, the police forces that met them were less like a military and more like loose-knit gangs. "America's police apparatus was hopelessly fragmented and uncoordinated," writes Parenti. "Whole regions of the country's law enforcement infrastructure were submerged in quagmires of nepotism, corruption and incompetence. In 1965, only four states mandated police training."

Police departments also lacked the equipment necessary for efficient, coordinated responses. For instance, not every cop had a radio in their car, and none had one on their person.

Police were able to concentrate overpowering force at specific targets, like civil rights marches, raids on the homes of Black Panthers, or protests outside the 1968 Democratic convention. But without specific orders and advance planning, individual police walking the beat were relatively isolated from one another.

Parenti describes how these shortcomings were recognized in the Presidential Crime Commission's 1967 report, which concluded that departments were "not organized in accordance with well-established principles of modern business management."

Bill Bratton's experiment with Broken Windows in New York City ushered in a highly managed, militarized police operation.

One of Bratton's first tasks was to raise the morale and seriousness of his force. Using money from Clinton's 1994 crime bill, Bratton hired 2,000 new cops, replaced police uniforms, and exchanged every cop's gun with a new Glock 9mm. Another way to get police to take their jobs with the utmost seriousness was to connect banal behavior to serious crime, the way Broken Windows did.

This connection allowed Bratton's police department to construct a massive intelligence-collecting operation. "Compstat" meetings were held weekly at NYPD headquarters, attended by all precinct captains, who stood before massive computer screens displaying maps of the city to supposedly explain crime trends.

The police today have come a long way from the "hopelessly fragmented and uncoordinated" forces of the past. That description sounds nothing like the police departments that waged a nationally coordinated crackdown on Occupy encampments in 2011, after weeks of planning and inter-departmental conference calls.

The same police force capable of clearing thousands of protesters from Zuccotti Park, with military precision is deployed every day in the New York's neighborhoods of color.

Bill de Blasio's campaign rhetoric about changing a "tale of two cities" rings increasingly hollow as he continues to support policies proven to target one of those two cities. The fact that de Blasio is on the left wing of the Democratic Party doesn't change the reactionary nature of Broken Windows. It only shows the extent to which the Democratic Party capitulated to conservatism over the past few decades.

That capitulation was made possible by the disappearance of powerful social movements in the 1970s. Which is why, left to his own devices, de Blasio is unlikely to change course on Broken Windows. It will be up to the Black Lives Matter movement to challenge Broken Windows--which will put activists in direct opposition to the city's widely hailed liberal mayor.