Snapshots from the Bay Area left

reviews a combination memoir, history and political statement written by a well-known activist in the Bay Area.

IF YOU'VE been politically active in the Bay Area any time during the last 20 years, as I have been, then you will know Chris Crass, or at least know of him. He has earned a lot of respect among activists based on his work in Food Not Bombs (FNB), and then as an anti-racist activist and trainer in the Challenging White Supremacy workshops, the Heads Up Collective and the Catalyst Project.

Widely-admired author and activist Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz wrote in a glowing Forward to Crass' Towards Collective Liberation that he is a mentor to a new generation of radicals. There are laudatory blurbs from the likes of historian Robin D.G. Kelley, legendary activist Elizabeth "Betita" Martinez, Black Lives Matter organizer Alicia Garza, Combahee River Collective founding member Barbara Smith, Malcolm X Grassroots Movement organizer Kali Akuno, and other left-wing voices such as Vijay Prashad, Maria Poblet and Silvia Federici, among many more.

Of all these, my favorite is from Yvonne Yen Liu of ColorLines.com, who locates Crass among a generation of activists who "refused to accept the end of history, that capitalism was the only way." As it turns out, I am a couple years older than Crass and also fit into what Jacobin editor Bhaskar Sunkara uncharitably (if lightheartedly) pegged as the "donut hole" of radical left politics--referring to the relative scarcity of long-term committed leftists who came of age politically in the late 1980s to early 1990s.

Our little generation is few in number compared both to the radicals of the 1960s and '70s struggles and the growing layer of young people entering left politics since the late 1990s, under the banners of global justice, the antiwar movement, Occupy, the Fight for 15 and Black Lives Matter.

Revolutionary politics in the years of the Reagan-Bush ascendency were not particularly common--and the last 25 years have been, some important victories notwithstanding, a period of working-class defeat. So I have a measure of respect for anyone who made it through this period and lived (politically speaking) to tell the tale.

TOWARDS COLLECTIVE Liberation is composed of four distinct, but related parts: Crass' autobiographical journey into radical politics; a social/political history of Food Not Bombs in the 1990s; an exposition of Crass' critique of oppression and capitalism; and a series of interviews with a variety of anti-racist and anti-poverty organizers from the Bay Area and beyond.

Bringing these strands together into a whole is at times a challenge, but Crass' conviction that a "vibrant and healthy democratic and socialist society" is within our reach helps bring the book into focus. Readers will be inspired by his optimism.

In this brief review, I want to focus on two points.

The first is about the concept of collective liberation--a phrase taken from bell hooks. Crass proposes this as a method to link the liberation of oppressed peoples with that of people described as possessing various kinds of privilege under capitalism, so that all can eventually unite to achieve socialism by means of mass, bottom-up, democratic movements.

The strength of Crass' thesis is the focus on collective struggle and systematic transformation, against an acceptance of a pluralist identity politics that simply aims to reapportion crumbs from the capitalist cake.

Crass rightly lays great stress on the structural and psychological impact of racism, sexism, homophobia and other forms of oppression. Yet, perhaps surprisingly, his view of a bottom-up revolution is not based firmly on the power of the working class to overcome its internal divisions and overturn capitalism. Rather, Crass' political strategy includes a wish for "middle and upper-class people to decolonize their minds and work with working class and poor people for an economic justice agenda with socialist values."

The danger with this cross-class perspective--which also includes tactical support for Democratic Party politicians--is that it can blunt the practice of building working-class power and fall into a sustained focus on individual subjectivity, as opposed to mass struggle.

Much of Crass' life has been dedicated to direct action, large and small, so he is adamant that our "complex intersectional analysis of systems of oppression and privilege" not serve as an excuse for falling into passivity on the basis that it is impossible to "address all the shortcomings" of past movements all at once.

Nevertheless, I can't help but feel that Crass' emphasis on personal subjectivity reflects his experiences in a certain kind of struggle that has, historically speaking, failed to reach a certain critical mass of social power. This is not his fault, of course. For many people active in politics today, our lives have been devoid of the large, multiracial class struggles dominant in other periods of U.S. history, or which have taken place internationally.

Crass is right to emphasize the need for organizers to confront oppression, but he often speaks as if the ideas of collective liberation will have to be brought to the working class from the enlightened organizers who have absorbed Stephen Covey's The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People, which he praises for its call to "begin with the end in mind."

This isn't to say that Crass proposes to rely on the enlightened few to do the thinking and doing. It's simply that the twin concepts of class struggle and ideological argumentation--via trainings, readings, workshops, etc.--aren't fully reconciled in his account, so he tends to speak of one and then the other, rather than a relationship between the two.

MY SECOND point deals with Crass' history of Food Not Bombs in San Francisco and elsewhere, from the late 1980s through to 9/11 in 2001 and beyond.

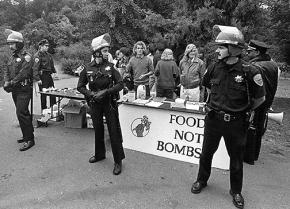

Crass was one of Food Not Bombs' central organizers beginning in the early 1990s, and his critical analysis of the group makes for fascinating reading--especially as someone who worked with and around FNB for years (hundreds of us were arrested together at a 1995 march for Mumia Abu-Jamal), but who could never quite figure out how it functioned. He describes the group's successes in defeating a string of anti-homeless measures taken by police and politicians, and at the same time, he pulls no punches when it comes to describing externally and internally generated fractures within the group.

Read alongside Max Elbaum's Revolution in the Air, the essay collection Ten Years that Shook the City, James Tracy's Dispatches Against Displacement and the STORM Collective's Reclaiming Revolution, among others, Collective Liberation helps paint a picture of one of the most tenacious and enduring left-wing movements and cultures in the country.

Unsurprisingly, there are times when Crass falls into an FNB-centric history of the period. Nevertheless, I realized that I never really appreciated Food Not Bombs as the well-defined political project he and many others conceived it to be. I'm not convinced FNB ever reached anything like the size and influence Crass claims--he estimates 50,000 members "at the low end" in the late 1990s in the U.S. and abroad--but it certainly was a critical component of the radical left in the Bay Area when I arrived in 1994.

It is in this spirit of historical reflection that I hope Crass reconsiders his dismissal of the Bay Area International Socialist Organization. He relegates our decades of work to what I consider to be an ill-informed and narrow-minded footnote--all we do is sell Socialist Worker, we stand on the sidelines, we never organize anything, etc.--which seems out of step with the rest of his approach.

In writing this review, I considered passing over this point without comment, but having spent almost my entire adult life operating in many of the same geographic and political spaces that Crass reviews in his book, it seemed dishonest not to lodge a protest.

OVER THE past 20 years, the Bay Area left has revived and fractured again along several lines, but we're still here. The most recent challenge we all face is the rapid restructuring--physically, demographically and politically--of the entire region by an unprecedented influx of high tech, real estate, finance and health industry capital.

Either the Bay Area left finds a way to rebuild a sense of unity and momentum that can help make possible a new round of rebellion from below, or the Tech Bros will remake our neighborhoods in their own image.

Recently, there have been hopeful signs of collaboration and growth on the left--ILWU Local 10's shutdown of the Port of Oakland on May Day in solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement was the most visible sign.

Many people connect this revival with the experience of Occupy Oakland. I won't disagree, except to say that Occupy Oakland was only possible because of the mobilizations against Oscar Grant's murder in 2009, and the hundreds of thousands of immigrants marching on May Day 2006, and the failed effort to stop the execution of Stan "Tookie" Williams in December 2005, and the Green Party's Matt Gonzalez almost winning the San Francisco mayoral election in 2003, and 250,000 people marching against the drive to invade Iraq in February 2003, and thousands going to Los Angeles to protest the 2000 Democratic National Convention, and the Battle in Seattle in 1999, and the UPS, BART and Contra Costa sanitation workers' picket lines in 1997, and the thousands marching for Mumia Abu-Jamal in 1995, and on and on.

In other words, if the resistance to global capitalism's outrages and the crystallization of the New Jim Crow state find expression in a bigger, more united left in the coming period in the Bay Area, then it is only because the left never stopped fighting. Disagreements aside, Crass' book contributes to our understanding of where we've been and where we need to go.