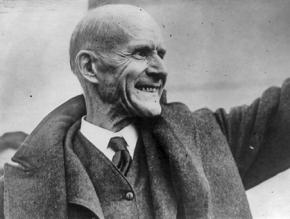

The measure of a revolutionary

Portland, Ore., writer looks at the life and legacy of the early 20th century socialist leader Eugene V. Debs, in an article for his Writers' Voice blog.

IN THE annals of American socialism, the name of Eugene V. Debs stands out as the most prominent personality in the movement's history. Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders, the self-described independent socialist now campaigning for the Democratic presidential nomination, considers Debs one of his heroes.

It's almost certain Debs would not have approved of Sanders running for the nomination of the Democratic Party. As a leader of the early 20th century Socialist Party, Debs once said he was more proud of going to jail for leading a rail workers strike than, early in his career, serving in the Indiana state legislature as an elected Democratic representative.

Unfortunately, there's a tendency among defenders of the status quo to turn great historical figures into harmless icons, saintly martyrs to high ideals who loved everyone and threatened no one. This, to a degree, has happened with the Rev. Martin Luther, King, Jr., a radical fighter for civil rights in his day, who the political establishment now treats with a kind of perfunctory reverence.

Sanders may have his own ideas about Debs' legacy, but at least he recognizes the historical significance of the socialist leader's life. These days, Debs (1855-1926) is not nearly as well known as King, or as he was in his own lifetime. In this way, the historical legacy of Debs has endured a similar affront, reducing him in popular culture to more or less a historical footnote. As such, conservative AFL-CIO bureaucrats probably don't mind referencing the old Debs legend as a labor hero once in a while, forgetting his militant opposition to the First World War or support for the Bolshevik-led 1917 revolution in Russia.

ACTUALLY, SOME of the sanitizing occurred while Debs was still alive, as in socialist editor David Karsner's sympathetic biographical portrayal of Debs published in 1919, when he was in federal prison for attacking the war effort and supporters were trying to win public sympathy to his case. But Debs was far more than the benevolent humanitarian with a little book of "kind sayings," as writer Floyd Dell of The Liberator complained about Karsner's portrayal, which he and others thought downplayed his revolutionary principles.

In fact, Debs was an articulate, far-reaching critic of American society, staunchly anti-capitalist and opposed to both Democratic and Republican parties, which he saw as controlled by Wall Street. In his five campaigns as the Socialist Party candidate for president of the United States, Debs excoriated the economic exploitation of workers, including the then-rampant abuses of child labor, with rare oratorical skill. He advocated for unions in all major industries and promoted a vision of socialism as grassroots economic democracy. In a deeply racist, patriarchal society, he was also staunchly anti-racist and pro-women's rights.

When war hysteria swept the country, Debs openly defied the warmongers to oppose U.S. entry into the First World War. He did so not as a pacifist, but because he saw the world war as an inter-imperialist dispute among the ruling classes of competing capitalist nations. He saw no reason for working people to die for a war they had not started nor in which they had any real stake.

Such was the climate of wartime intolerance that Debs was charged with sedition for making a speech against the war in Canton, Ohio, in June 1918. His sentence was 10 years in prison. The sedition charge fell under the Espionage Act of 1917, a law promoted by President Woodrow Wilson that essentially criminalized free speech. Indeed, under the wartime repression, several thousand labor, anarchist, socialist, and pacifist voices were similarly prosecuted. Even distribution of antiwar literature through the U.S. mail became illegal. For his part, Wilson labeled Debs a "traitor."

Debs appealed the conviction, but in 1919 the U.S. Supreme Court upheld his original 10-year sentence. The court took precedent from a similar case earlier that year involving another convicted Socialist Party leader. Then Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes had made the famous argument that free speech didn't mean the right to yell "fire" in a crowded theater. Holmes' metaphor was specious. In this case, the crowded theater was a European battlefield red in blood and violence, the fire of inter-imperialist war and millions of casualties very much a reality. In truth, Debs was yelling "fire" in a burning theater, enraging the likes of the sanctimonious Wilson by identifying the ruling classes of Europe and America for what they essentially were--arsonists of human hope and civilization. Mass murderers.

If the "liberal" Wilson had his way, the aging Debs would have stayed in prison for the full sentence--and likely died there. When word came in 1920 of Wilson's refusal to commute Debs' sentence, despite notable public pressure to do so, the socialist leader smuggled a statement out of the prison denouncing Wilson as "the most pathetic figure in the world. It is he, not I, who needs a pardon," declared a defiant Debs.

Ironically, it was Republican President Warren G. Harding who would commute Debs' sentence in December 1921. Considering that even A. Mitchell Palmer, the U.S. Attorney General who led many of the wartime raids and arrests of radicals, had come to favor Debs' release from prison, it's likely Wilson's personal vindictiveness toward Debs was fueled by the way the latter's principled antiwar stance exposed the hypocrisy of the President's moralistic posturing as some sort of progressive visionary of "world peace."

Such was the world of that time that the man who sent some 116,000 young Americans to their battlefield deaths, who took a hammer blow to the free speech rights of peace advocates, would be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1919. Yet Debs, who never killed anyone and was guilty only of the deed of the word, had his freedom cruelly taken away. Such a world also remains. Now another Nobel Prize winner in the White House embraces this same Espionage Act with vigor unprecedented since Wilson's day. This time the persecuted include Chelsea Manning, Edward Snowden, John Kiriakou and other "whistleblowers" who dare to expose U.S. war crimes and threats to political freedoms by the U.S national security state.

AS A principled left-wing socialist, Debs was cut from a different cloth than most mainstream politicians, then and now. How many career politicians today would be willing to go to prison for their views and ideals? In the 2008 primary campaign, then-Democratic Senator Barack Obama couldn't even bring himself to openly declare his support for same sex marriage rights, which he did in fact privately support. Instead, fearful of losing votes, he publicly insisted he only supported "civil unions" for gays and lesbians.

This admission comes from former Obama advisor David Axelrod in his recently published book, Believer: My Forty Years in Politics. Obama was following Axelrod's advice to lie about the issue, counseling the future president that he would lose support from conservative Black churches. That's not to particularly single out Obama. After all, that's just politics!

Actually, for Debs that was not politics. For him, political leadership always meant telling the people the truth. "I am not going to say anything that I do not think," declared Debs in the 1918 speech that earned his conviction for sedition. Debs believed in organizing working people to realize their own power, through independent social and political action, union organizing, and building grassroots mass movements for social justice. It was a vision of a new society that inspired him, one in which popular economic democracy would rule and inequality and exploitation would be vanquished to history's proverbial dustbin.

Sustained by his identification with the socialist cause, Debs went to prison at the age of 63 characteristically optimistic and defiant. After a few months in a West Virginia facility, he was transferred to the federal penitentiary in Atlanta. Debs did not exactly languish in prison. In 1920 he ran for president in the national elections on the Socialist Party ticket, earning over 900,000 votes, or about 3.5 percent of the total vote. Indeed, his fighting spirit remained strong. But Debs was also in poor health in prison. He suffered from chronic myocarditis, an inflammation of the heart muscle, a condition he had for much of his adult life. The stress of the prison environment, including poor nutrition, caused his health to worsen. At times he was hospitalized, while his weight dropped from 185 pounds to 160.

When finally released in December 1921, Debs returned home to Terre Haute, Indiana, greeted by an enthusiastic crowd of more than 30,000 people. There he hoped to rest and regain his strength, but as the months passed his health did not improve. In the summer of 1922, Debs decided to register as a patient at the naturopathic Lindlahr Sanitarium in the Chicago suburb of Elmhurst, Illinois.

Debs stayed at Lindlahr for more than four months, benefiting from a strict but healthful diet, exercise, physical therapy, nature walks and other restorative treatments. He became fond of the Lindlahr staff, telling his brother that his palpitations, back pain and exhaustion had lessened considerably as a result of the "nature cure" regimen he was following.

Debs returned to work for the Socialist Party, speaking around the country, and returned again to Lindlahr in 1924. Unfortunately, by 1926 Debs health began to take another turn for the worse. Larger doses of digitalis prescribed by his Terre Haute physician Madge Stephens could not reverse his failing heart condition. In the final weeks of his life, Debs returned to Lindlahr on Dr. Stephen's advice, hoping for yet another reprieve from his suffering. After collapsing while walking back from a visit at the nearby home of friend Carl Sandburg, Debs lapsed into a coma and died on October 20. He was 70 years old.

AS A politician, Debs was primarily a speaker and writer, skills he used to great effect in his campaigns for elected office. As a party leader, Debs had a tendency to avoid the many internal factional debates in the all-inclusive Socialist Party. In doing so he sometimes became, as contemporary socialist and early Communist Party leader James P. Cannon later recalled, a pawn of those who by every measure were far less the leader Debs was.

Yet perhaps even this weakness stemmed from one of Debs attributes. By nature Debs was an engaged, generous personality, capable of "beautiful friendliness," as Cannon described. As a man steeped in the spirit of human solidarity, it went against the grain of his personality to engage too much in the sometimes heated, vituperative debates that can mark the internal life of a political party. Instead Debs preferred to reserve the full flame of his words and spirit for those who oppressed the ordinary people, the poor, the dispossessed and exploited whose cause he spent his life championing.

Whatever his limits, the record of Debs stands in tribute to the heights an individual can ascend in devoting their life to the cause of human liberation. Unlike a wealthy narcissist like Donald Trump, Debs saw himself essentially only as an instrument of the cause he served. When in the 1920s Carl Sandburg told him he hoped to write a tribute to his friend, Debs begged off, telling the great writer and poet he feared there was "not enough of me to warrant any such venture." Nor was Debs a politician like Hillary Clinton, long ensconced in the visionless "realpolitik" of the Washington beltway, a liberal war hawk and friend of Wall Street, charging private groups $200,000 or more a speech. Neither was his brand of socialism limited to democratic reform of capitalism, to softening the harsh facts of inequality under capitalism without getting rid of capitalism itself, as Bernie Sanders represents.

The life and legacy of Eugene V. Debs stands as a rich and vibrant testament to one man's dedication to a liberated future. Indeed, Debs was an individual for whom solidarity with his fellow humans was in his blood. Debs also thought for himself, and he evolved. His experience as a labor organizer for the American Railway Union pushed him toward socialism, which he didn't embrace until he was nearly 40 years old. Once he did he never looked back, abandoning the more conservative outlook of his younger years. As a socialist, Debs denounced as irrational and unjust a capitalist system that created extravagant wealth for a few at the top, while millions of ordinary working people struggled to get by. Most important, he thought it was possible to build a new, cooperative society, to transcend the irrationality, waste, and greed of the capitalist economic system, and to end wage slavery and all forms of social oppression. He called this socialism.

COINCIDENTALLY, DURING Debs' last stay at Lindlahr in 1926, Cannon, then national secretary of the International Labor Defense (ILD), a civil rights group established by the Workers (Communist) Party to defend political prisoners, was also a patient at the Elmhurst clinic. When the ILD was established the year before, Debs in typical fashion had offered to serve on its national committee.

While at Lindlahr, Cannon's partner, Rose Karsner, recalls how they wanted very much to talk to Debs, but under the circumstances were hesitant to intrude upon the ailing man. On the day after their arrival, Karsner saw Debs sitting in the reception room while waiting for his room to be made up. In the moment she decided to very briefly say hello to Debs.

"I went over to Gene and attempted to make myself known, but I believe he did not get my name," recalled Karsner in a letter written on ILD letterhead to Theodore Debs a week after his brother's death. "It was quite clear to me that he was very weak and I tried to get away. But Gene, in his characteristic way, would not permit me to leave. He did not know who I was, but he heard me say 'comrade' and that was enough for him. He sat and spoke to me for a few seconds."

As Karsner concluded:

Personally, I feel that Gene belonged to us all and especially to those of us engaged in work which characterized his activities most--the united action of ALL in behalf of the working class, regardless of political, industrial, or philosophical opinions. He rose above party differences and factional lines, and we love him for it. The tradition of Gene is the greatest treasure of the younger generation.

In the twilight of his days, there was revealed perhaps in that fleeing moment with Rose Karsner something of the full measure of Eugene V. Debs, a man for whom the word "comrade" was always enough for him.