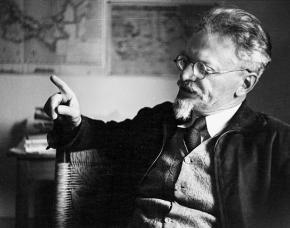

The indispensable Trotsky

reviews a brief book about one of the 20th century's revolutionary giants.

THE RUSSIAN revolutionary Vladimir Lenin once remarked that without revolutionary theory, there can be no revolutionary practice. Forty-five years into neoliberalism's attempt to erase all memory of socialism, or even basic human decency, the U.S. is today witnessing a new outburst of enthusiasm for the "S" word--most notably, but not only, through Bernie Sanders' campaign for president.

Paul Le Blanc's new biography Leon Trotsky offers a strong jolt of the kind of history and theory needed if his readers--especially younger ones--are to build up socialism as a revolutionary force in U.S. politics.

Le Blanc is at pains to stress Trotsky's "unoriginality" --in the sense of his firm grounding within and development of a long tradition of working-class revolutionary politics. Yet in the context of contemporary U.S. politics, these ideas are provocative, out of the ordinary.

But as we mark the 75th anniversary of Trotsky's assassination by a Stalinist hit man, young readers might well ask why they should bother. As it turns out, aside from the drama and grandeur of an intrinsically fascinating career, near the end of his life, Trotsky was attempting to reach exactly the same sort of audience Le Blanc is after.

TROTSKY DEFINED his only truly indispensable contribution to the working class as his defense of the genuine Marxist tradition and history of the Russian Revolution in the 1930s from the distortions of Stalinism. He strove to pass along their lessons to a few dozens of younger organizers and a few thousands of their followers.

This idea that the most important part of Trotsky's life came when he was most isolated appears on its face to be absurd.

After all, Trotsky was arguably the best-known figure in all of Europe--more so than Lenin--from 1917 until his exile from the then-USSR in 1928. Friend and foe alike acknowledged this wunderkind--elected president of the 1905 Petrograd Soviet at age 26--as the continent's greatest orator, as the sword of the Russian Revolution, as that wonderfully ambiguous word bolsheviki made flesh. He personified, like Malcolm X and Che Guevara after him, the highest hopes and most determined commitments of a generation.

So why did Trotsky judge his final decade, when he was banished from the global stage, to be so important?

Simply put, without Trotsky, the identification of revolutionary socialism, of the self-emancipation of the working class, of Marxism as a liberatory theory and practice, might have been strangled in the gulag. Thousands were repulsed by the brutality and hypocrisy of the counterrevolution in Russia led by Stalin, but their scattered protests required a rallying point to stop the retreat and carve out politically (and physically) defensible positions from which a future advance might be organized.

Trotsky's keen intellect and his indisputable credentials allowed his views to puncture the dual agonies of fascism and Stalinism, and gain a hearing. If no longer the voice of the Revolution, Trotsky served as its conscience. And the small but dogged forces he fought to gather together rescued the Revolution's better angels from oblivion. Their wings broken, there were able to speak.

In the absence of Trotsky's work during these terrible years, the struggle of future generations to counter Margaret Thatcher's famous dictum "There Is No Alternative" to capitalism would be immeasurably more difficult, even hard to imagine.

PAIRING ACCESSIBLE prose with just enough historical detail to set the stage, Le Blanc packs the major episodes in Trotsky's life into just over 200 pages, while setting out and commenting critically on his best-known theoretical contributions.

Among these, Le Blanc reviews Trotsky's economic analysis of combined and uneven development, the tactics of the united front, criticism of the Soviet bureaucracy, anti-fascist strategy, transitional demands and political programs, and methods of international revolutionary organization. Le Blanc's clarity guides readers unfamiliar with this history through what can otherwise be an easily bewildering landscape.

Achieving efficiency of this scale inevitably leaves Leon Trotsky open to criticism over points of interpretation at times.

By way of example, Trotsky's refusal to submit to Stalin's counterrevolution stands as one of his main historical contributions, and Le Blanc recounts this fight with a keen Marxist analysis that gives proper weight to material and ideological circumstances.

"There was a method in the madness," writes Le Blanc. "What Marx called primitive capitalist accumulation--involving massively inhumane means (which included the slave trade and genocide against native peoples, as well as destroying the livelihood of millions of peasants and brutalizing the working class during the early days of industrialization)--had created the basis for a modern capitalist industrial economy."

To my mind, if you don't understand this dynamic--and believe instead that revolutions can simply end in tyranny for no reason at all, or only because a single individual desires power--then there is little hope for humanity. Here, Le Blanc is spot on.

However, in documenting the early stages of this fight, Le Blanc denotes Trotsky as a "Communist Authoritarian," arguing that "Lenin, Trotsky and other leaders had by 1922 crushed oppositional currents--the Workers' Opposition, Democratic Centralists and others--whose perspectives had been rooted deeply in Bolshevik ideals that culminated in the 1917 triumph."

Le Blanc is right to point out--as Rosa Luxemburg did some years earlier--a tendency among Bolshevik leaders to make a virtue of necessity during the Revolution's darkest days.

But this is one of the few instances when Le Blanc does not provide sufficient weight to the objective circumstances which forced many of these choices on them. For instance, Le Blanc places scant emphasis on the brutal post-1917 Civil War that set the stage for emergency measures--perceived as extraordinary and temporary, in the face of an unforeseen and unprecedented crisis--restricting workers' democracy.

This criticism aside, Le Blanc presents his case in a crisp, no-nonsense manner that helps facilitate a more fully informed debate, rather than shutting it down.

SIMILARLY, LE Blanc's treatment of Trotsky's conception of permanent revolution--what is usually considered his most important (and controversial) contribution to Marxist theory--is as concise at it is provocative. He writes:

Trotsky's version of the theory contained three basic points: (1) The revolutionary struggle for democracy in Russia could only be won under the leadership of the working class, with the support of the peasant majority. (2) This democratic revolution would begin in Russia a transitional period in which all political, social, cultural and economic relations would continue to be in flux, leading in the direction of socialism. (3) This transition would be part of, and would help to advance, and must also be furthered by, an international revolutionary process.

I think this is a very helpful summary. This broad view of permanent revolution has been challenged recently by Marxist author and activist Neil Davidson, who believes that Trotsky's theory only functions in more narrow circumstances and is no longer applicable. Le Blanc and Davidson have discussed these different conceptions elsewhere, and Leon Trotsky does not refer explicitly to this ongoing exchange, but Le Blanc's defense of the theory's contemporary relevance typically helps clarify the terms of the debate:

One might go further: permanent revolution has applications in the capitalist heartland, not simply in the periphery. Struggles for genuine democracy, struggles to end militarism and imperialist wars, struggles to defend the environment from the devastation generated by the capital accumulation process, struggles simply to preserve the quality of life for a majority of the people, cannot be secured without the working class coming to power and overturning capitalism. Such struggles in the here and now also have a "permanentist" dynamic.

I am partial to Le Blanc's views here, but whether one rejects this position or accepts it in whole or in part, it is precisely the sort of discussion that links history and theory to the struggles we face today.

GIVEN TROTSKY'S preeminently political life, Le Blanc could be forgiven for concentrating solely on his public role, leaving aside a portrait of his personality. But Le Blanc takes on the challenge, even if he leaves us with an ambiguous assessment.

Here, we face the classic nature-and-nurture debate. What part of Trotsky's reputed self-possession, iron will and driving confidence did he bring to the revolutionary movement, and what part of those traits were imparted to him by the movement itself? Is it possible to separate a figure like Trotsky from a great historical process he was, for his entire adult life, so intimately associated with?

Attempting to untangle this dilemma, Le Blanc reports Comintern leader Angelica Balabanoff's assessment:

Trotsky proved himself capable of arousing the masses by the force of his revolutionary temperament and his brilliant intellectual gifts...[However], his arrogance equals his gifts and capacities, and creates very often a distance between himself and those about him which excludes both personal warmth and any feeling of equality and reciprocity.

At the other extreme are the remarks of a collaborator, U.S. Socialist Workers Party leader Joe Hansen: "The word that occurred to me was mellowness; yet that was not quite right...He did not seem to drive others as hard as he had before. He had more consideration, I felt, for weaknesses in his collaborators. It was subtle but definitely there."

Is it possible to choose between "arrogance" and "mellowness" given the gulf between circumstances? Can we say that one is "better," in a moral sense, than the other?

Between these two extremes lay a 45-year political career spanning some of the most inspiring and terrifying moments in human history. What I find fascinating about Trotsky the man is that, perhaps more than any other revolutionary figure, the interplay between individual and social force persists for decades, and Le Blanc helps explain why this is so.

In a very real way, Trotsky's life is the story of the first half of the 20th century, and no one book can possibly do it justice. But if you are not familiar with Trotsky and the Russian Revolution and are looking for a place to begin, you can do no better than Le Blanc's book. And if you are a veteran of this history, you will be challenged and invigorated by his point of view.