The truth about Rikers Island

Mary E. Buser, the author of a new book that tells the stories of those locked up on Rikers Island, talked to in an interview published at Jacobin.

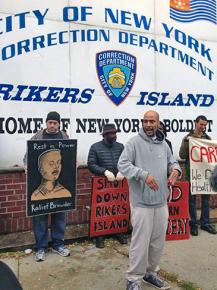

RIKERS ISLAND, New York City's 415-acre jail complex on the East River, houses anywhere from 9,700 to 15,000 people on any given day. A number of high-profile cases--most prominently, that of 22-year-old Kalief Browder, who committed suicide in his mother's home after spending three years, two in solitary confinement, on Rikers, only to have all his charges dropped--have generated increasing scrutiny that has reached well beyond prison abolition and prisoner rights activists.

Indeed, a public debate, involving activists, racial justice organizations and public officials, has been ignited about whether reforms of the scandal-filled complex are feasible, or whether the entire complex should be shuttered.

Mary E. Buser first set foot onto Rikers Island in 1991. An eager graduate student at Columbia University's School of Social Work, she had high hopes for her yearlong internship providing therapeutic services to the women detained at the Rose M. Singer Center, the only women's facility on the island.

Then, in 1995, she accepted a permanent position in the mental health department on the island, working first at the George Motchan Detention Center. Following her promotion to assistant chief of mental health, she was transferred to the Anna M. Kross Center and finally to the Otis Bantum Correctional Center, which houses the Central Punitive Segregation Unit--otherwise known as solitary confinement--where she would remain until her departure in 2000.

These five years coincided with the mayorship of Rudolph Giuliani and the beginning of the implementation of "broken windows" policing. At the time, there was a record 24,000 detainees incarcerated at Rikers.

While Buser began her career at Rikers with a deeply held commitment to helping people through some of the most difficult moments in their lives, what she learned about how the criminal justice system in the U.S. functions, as well as the resulting daily inhumanities that she witnessed, forced her to question her own role within it.

She made the courageous decision not only to resign from her position, but to detail her experience and to tell the stories of those detained there in her new book, Lockdown on Rikers. Buser was interviewed for Jacobin by Lichi D’Amelio, a New York City-based activist and member of the International Socialist Organization and the Campaign to Shut Down Rikers.

AMID THE public discussion about the brutality on Rikers Island, your book Lockdown on Rikers has served as an invaluable up-close testimony on the topic. You began your work there 20 years ago as a social work intern. Why are we only hearing your story now?

I WAS trying for many years to get it published, but there were some barriers. First of all, I was always a decent writer, but I've never done anything in the book length. It took me some years to write it. Second, the time was not quite right. I kept beating my head against the wall, feeling like, I have a story to tell, and I can't find a way to do it.

But then it just went into full speed after so many years of trying to get it out there. In some ways, I'm really grateful for the timing because when I was writing it, and I wrote about the brutality, I kept saying to myself, “Who is going to believe me? No one is going to believe this because it was not in the news.” It would just be periodic news blurbs that were barely read, quickly forgotten, and that would be it. Nothing like we're seeing now.

When the New York Times started really penetrating Rikers Island and getting these stories out about the violence, it was very validating for me--that big worry of mine, that no one is going to believe it, disappeared.

YOUR BOOK also illuminates who ends up at Rikers and why. You, for example, tell a story about a man who you call Hector Rodriguez, who was unable to see his mother before she died because he couldn't pay bail. Are there a lot of stories like this?

YES. I met him when I first started working with the George Motchan Detention Center, otherwise known as C73. There were a couple aspects of his case that were very disturbing to me. The first one being that, as everyone is starting to learn about Rikers, it's primarily for pre-trial detainees. The reason that they are in jail while they're waiting for their "day in court" is because of the inability to pay bail.

It is such a bias against the poor. It sounds very clinical, but the consequences are horrible. In his case, the bail was a few hundred dollars, which just shows just how impoverished people are that they couldn't come up with that.

What was even more disturbing to me was the fact that Rikers Island is very difficult to get to. When I was a student (working as an intern there), I was in a carpool--that helped. I live in Brooklyn, and for me to get to Rikers Island without a car is easily two hours by train and bus. The people who are on Rikers--they're poor, they can't afford bail, their families don't have cars. It is a very arduous trip for their families to get to see them.

This is terrible because people need their families, and though they are "presumed innocent," they're kind of exiled here. In the case of Hector Rodriguez, he just said, "My mother is sick, she'll never be able to make that trip." I was so struck by that.

His worst fear was realized a few months later when he was at the clinic sobbing that his mother was dead. He said, "For lack of a few hundred bucks, I couldn't make bail, be home, go to the hospital." He hadn't even been convicted of anything.

That's the reality of it that I would see day in and day out. I would just be stunned by the inequities and how anything goes when it comes to people who don't have money.

YOU ALSO talk in the book about what it means to have to fight legal charges from behind bars. You argue that it pushes people towards plea bargains.

FIGHTING A case behind bars is very, very difficult to do, and it functions as a type of leverage against the poor. Being behind bars on Rikers Island serves as a massive arm twist to get people to accept the plea bargain. They would agree to anything to get the hell out of there. In the beginning, I would work with people who would say, "I didn't do anything and I'm going to have my day in court."

I was like the average American, I believed in the ideals of the system. I would respond, "That's right, if you didn't do it, you'll never say you did something that you did not do." Then I began to see what they were up against, and that's what the public does not realize.

On the outside, we have this notion that everyone's guaranteed their day in court. If you really want that, you can sit there for years on end waiting for that day in court. The prime example, of course, is Kalief Browder, who refused the plea bargain. He was so badly traumatized, physically and emotionally on Rikers Island--after his release, he was never able to recover and he committed suicide.

There are many Kalief Browders in the same predicament who say, "I didn't do anything." Now, most people don't realize that the Sixth Amendment guarantee of a speedy trial is a false guarantee. It's nothing; it's a piece of paper. I started to learn the reasons since I would sit there and tell people, "No, hold on. I'll meet with you several times a week. I'm going to provide the moral support for you to see your day in court."

I started reading to understand what was happening. In the '90s and the mid-'90s--I don't know the exact numbers, but I can get pretty close--you have around 125,000 felony charges, and the courts, let's say in the borough of Manhattan, had the capacity to try 1,300 year. You have 123,700 cases that in that year cannot be tried. So of necessity, they must be plea-bargained. It's a matter of logistics; it has nothing to do with justice or ideals, it has to do with practicalities.

If we go back to the moment that you're charged and bail is set, if you can afford to pay it and go home, you can wait it out for years. Which is not ideal, it would be hard for anyone to wait that long. If you can't make that bail, you are going to sit behind bars for that length of time, for years. On top of fighting your case, you've got to survive jail. You're going to be cut off from your family, you lose your freedom, you have to endure not only the indignities of jail but the violence and the fear.

At one point I remember saying to one guy, I was trying so hard to get him to hold on because he just said, "I didn't do anything, I was just plucked off the streets." Everything about his behavior validated that to me. I just kept saying, "Hold on, hold on." And when he started to waver, I said, "No, this will all be over." He just looked at me and said, "You go home at night, I don't."

I had to back off because it was the truth, and terrible things happen at night.

All of a sudden waiting for trial becomes secondary to survival. If you have been marked by other inmates, you don't have a lot of choices. You can't go to corrections and say, "I'm scared in this house, could you move me?" They'll laugh at you. If you have somehow gotten a beef with an officer and you're in danger of being beaten, well, what does your out become? I'll take that plea bargain.

And that's what would happen. I came to understand that people had to forgo their futures and forgo the truth for the sake of surviving the moment.

Kalief Browder was such a courageous young man because what he endured--he was beaten and you can see the film footage of it. He was thrown into solitary confinement and he was told in court, "If you just agree that you did it, we will release you on time served. We'll say you served your punishment for swiping the backpack. Just say you did it, and you can go home." That kid stood there and said, "I will not say that." Knowing that he would now be put on a bus and put right back into this hellhole.

Three years later, they finally just dismissed the charges. There's never been a case against him.

Most people succumb. If you watch interviews with Kalief Browder, he would say, "Not everyone is as strong as I was but so many people are in the same position I am." The plea bargain is expedient. Trial is years away, and you live in this limbo-like existence. People start asking themselves, "I have to be crazy not to take the plea." Even if they're innocent.

If you're poor and you have to factor Rikers Island into your wait for trial, you almost have to be superhuman to pull it off. That's what I witnessed, one by one [my patients] would be sheepish, "Miss B., I know but I have to get out of here. I have to get on with my life. I have an ailing mother or someone at home. I have to get out. I have a family that needs me to make some money. I can't sit here for years on end. I have to do what makes sense."

They have to stand there and say they did it. Everyone knows they don't feel they did it, but they have to say it. Typically they get slapped with a felony. What that means now is a lifelong stain and the person will be relegated to a fringe-type existence: always scrambling for a job, always having to explain away the felony.

YOU ALSO describe a tension between the mental health staff, who you worked with, and the Department of Corrections when it came to people with mental illnesses. Some 40 percent of people confined at Rikers suffer from mental health issues.

WHAT IT taught me in the end is that jail is not the place for the mentally ill. I don't think that there's any way that it can ever be retrofitted to take care appropriately and humanely of the mentally ill.

First of all, the mentally ill were openly referred to as "nuts" right to their faces. "How many nuts do we have? We've got five nuts. Come on nuts, come this way." No matter how many times I heard it, I winced and it made no difference. You couldn't say, "Please don't speak that way." You'd just be laughed at. Your heart broke to see people being spoken to like that, people who are trying so hard to organize their brains or fight depression.

The Department of Corrections had a lot of issues with us. They felt that we were mollycoddling people. Their view was that the mentally ill were just always trying to "get over." As much as we would try to explain to them, "This person has bipolar disorder, could you be a little patient until the medication kicks in?" You'd always get some smart remark like, "We know how to alter their behavior real quick. Why don't you just let us take care of it?" That was the prevalent attitude. Violence.

They would manage everything. There was always tension because the mental observation units, we controlled those units. It's a little hard to explain, but a mental observation unit is simply another housing unit in the jail. Even though there are 10 buildings there, each jail has its own clinic--its own observation units for that jail's mentally ill. We would interview people and evaluate them. If someone appeared psychotic or mentally ill, we would take them out of the general population and transfer them onto a mental observation unit.

Now, when I was at the George Motcham Detention Center, we had two units. One was the dorm, just rows of cots, the other was a cell block which was cells with a day room. If we thought that someone was suicidal, we didn't want them in the cell block, we would want them in the dorm where they could be openly observed. If we thought that someone was really psychotic, a dorm could be too stimulating. They would do better in a cell until they get stabilized on medication. Generally speaking, that's the way we did it. However, just put that aside for the moment.

Every inmate in that jail and in fact on Rikers has a security number attached to them. That number is calculated by the Department of Corrections based on what your charges are and problems you may have had inside the jail. The higher the number, the higher the security risk. Those people would always go into general population to cell blocks instead of dorms. People with lower numbers would go to the dorms.

But, when it came to mental observation units, if we had someone who was highly suicidal, we're not going to put him in a cell, we are going to put them in the dorm. The DOC would have a fit because they would say if it was someone with a higher security number they wanted them in a cell. They would be at our door. "He has a high-security number! He can't be in the dorm!" Ultimately, it was our call because the risk of suicide always trumped security.

I had so many battles with them. We always did because they would push us and say, "That guy is not going to kill himself, he is just trying to get over." We would say, "Be that as it may, he's staying in the dorm." They knew that we had the final say on it, and they hated it. They hated the fact that we had this authority in "their jail."

Yet if someone committed suicide in that cell because we caved into their pressure, we would be responsible for having made the wrong call. They would be in our faces, so to speak, every step of the way: "There's nothing wrong with that guy," rolling their eyes.

AND THE DOC had special units, right? The ERSU--what they called "the Ninja Turtles." Who were they?

IT'S TERRIFYING. The ERSU stands for Emergency Response Service Unit. It's a special unit of corrections officers who are essentially of gargantuan proportions; they're huge. I would be in the sally port sometimes with them and feel like I was looking at their navels. They were so big. They were basically used for force.

They would go from jail to jail, wherever they were called. If there was some issue in the jail, some kind of eruption, they would come in. They had heavy black boots and they wore this padded stuff--almost like a catcher in baseball with helmets.

Because of that padding they looked like Ninja Turtles, so that was their nickname. People would say, "The ninjas are coming." Their nickname was also the goon squad. They would really mete out force and intimidation. They were again kind of this elite unit available at a moment's notice to quell an uprising. They were very scary.

WERE THEY used often?

YES. I would say they were used very often. I have a story in my book about when I was at Otis Bantum Correctional Center on our mental observation unit, and a razor blade went missing. The whole dorm was put on what they call "the burn."

It was terrible. Someone somehow got out with a razor blade, and it was the DOC's fault. They did not accurately check, as they usually did, that everyone had turned their shaving razors back in. All hell broke loose.

I was standing there listening to the security team screaming at the mentally ill, "You should never have never been born, you think you're fooling all these mental health people, all these doctors, with your mental illness crap but you're not fooling us!" Just slamming his police billy club or whatever it is against the cots. It was so frightening to hear the way he was threatening and berating everyone.

At the same time, the "ninja turtles" were on their way--along with this chair that they use to make people sit on to try and detect any metal inside their body. It turned up nothing and the ninjas raided the unit.

It wasn't like they came in there thinking, "This is a mentally ill unit, we have to be conscious of that." It didn't matter to them at all. They probably took some pleasure asserting themselves with the mentally ill. It was bad.

THIS WAS at the Otis Bantum Center, where you spent your final days at Rikers. This is where they house "the bing," the punitive segregation unit, or solitary confinement. Can you speak a little about that?

MOST DEFINITELY. It is so important to talk about because in the United States today, somewhere between 80,000 and 100,000 people are being held in solitary confinement.

It says something about who we are as a society. It's so inconsistent with what our ideals are. The UN rapporteur on torture has said anything after 15 days in solitary constitutes torture.

Speaking from my specific experience, I first was introduced to Rikers Island through an internship when I was a graduate student in Columbia University. What I heard about solitary was that it was for "the worst of the worst, the baddest of the bad." It was something that I was very removed from and I hoped that it would remain that way--but it seemed in some ways I was fated to wind up in the thick of it.

When I returned to Rikers upon accepting a job after my internship, I worked in the men's jail. I became much more aware of solitary. The Central Punitive Segregation Unit is its official name. It was 500 cells contained in a five-story tower of 100 cells on each floor. Kind of a jail within a jail. If you committed an infraction--and it could range from disobeying an order all the way to assault on staff--you could be sent to the bing.

On my first day there, I really learned what I was in for when the chief--I was the assistant chief at that point--informed me that the mental health department was a huge presence in the bing. She said that the demand on us in the bing was immense. She said that virtually everyone was on medication. She said if they had no mental health issues before they entered solitary, they do now.

I just thought, my God, what kind of punishment is it that breaks you down so badly mentally and psychologically that we are propping you up with medication to endure it? In that first week, I was brought to the office of the deputy warden of the bing. He just said, "Anything I can do for mental health, you let me know because it's your presence and the medication that makes this place slightly manageable."

It was really a horror show. When the medication could really no longer hold a human psyche together, we would be called to a cell door where we would find the officer who would unlock it. We would have been called for reasons that could possibly endanger someone's life. Head banging, arm slashing, makeshift nooses.

There would be a desperate person behind that door begging for a reprieve and the mental health department had the authority to authorize it--but we were under fierce pressure to not give in, to not be "played."

We would do almost anything to not let someone out, but in the event that we thought that someone might actually die, then--and only then--could we authorize a temporary release. And they would be bused to a small unit down the road only long enough until they recovered. Once they recovered, they would be bused right back again. DOC would not cut their sentences. The only way out was through mental health.

Consequently, people would try to show us just how desperate they were so that we would authorize that release. You get into kind of a tug of war with people and yet the lengths they would be willing to go to absolutely endangered their lives. Which told you just how grueling this punishment was.

And it wasn't isolated. That was the really horrible part. I would be called to a cell door almost every single day and stand and talk to someone--and try to get them to endure the punishment a little bit longer...

It was very tough.

I was dazed because I would see the blood. I would see someone's skull, terrible things, people babbling incoherently. All induced by this punishment. Yet, when I walked over, I would tell myself it can't be that bad because the United States prohibits cruel and unusual punishment. It can't really be that bad because this is standard punishment in jails and prisons across the country.

I would literally try to visualize the American flag flying over the building. Thinking, "I'm in a safe place; I'm part of the good guys. Human rights violations occur elsewhere, never here." So I had this battle raging within myself, and I would tell myself that this is really okay. But, when I would get there--every time my knees would just be wobbling anyways.

I reached the point when that battle that I had within myself finally won out. I thought, "I can't be part of this anymore but I'm not going to forget either. I'm going to find a way to tell people." That became my next mission: help, this time from the outside.

YOU HAVE this incredible quote describing you and your team having to make a decision about a person. You write, "As we looked into each other's eyes trying to make the right decision, I had an awareness that I was now a monitor of human suffering and that all of us were making decisions no person should ever be asked to make." I thought that was really powerful.

THANK YOU. I remember writing it, and it was tough to write those words! No person should be asked to stand there and decide if someone will make it another day. Could he lose that arm? I'm standing there saying all this stuff, and I'm like, my god. I would have these flashbacks to my early days on Rikers--this idealistic person who was going to make a difference and there we were huddled, and that would be the conversation.

Ultimately, we did become a monitor of human suffering. We would look to see if they cut their arm one way; well that meant one thing. They cut their arm that way; that meant something else. You got to be like a specialist in this. You're gauging by their actions just how likely they were to die.

WERE YOU following what recently happened with Jason Echevarria's case, whose family just received a settlement?

ACTUALLY, PART of my dedication of the book is to him--and Jerome Murdough. May he rest in peace.

I do think that I'm seeing a groundswell of interest and recognition in this country of something that has gone badly wrong. But there is this nationwide tension. There was the Pelican Bay hunger strike, which challenged the horrendous solitary confinement situation there.

But it's not just solitary. Solitary is perhaps the most egregious and visible aspect of it. There is the judicial unfairness, just the way the poor are mistreated through the criminal justice system. The whole bail issue.

One area where I'm not seeing much change is when it comes to the mentally ill. When the big state hospitals were shut down years ago, it was with the promise that smaller community-based housing would be built, where people could live. This was supposed to come to pass and it never materialized.

Now it's just a free-for-all. Many people can't cut it on medication alone. They need supervision; they need housing. People end up out on the streets, they get into trouble with the police usually for petty mischief, and wind up on Rikers Island.

I would like to see them get the mentally ill out of our jails and prisons. It is inexcusable that people charged with trespassing could then bake to death in their cell--which is what occurred with Jerome Murdough. It's beyond horrendous. Then the bail issue has to be addressed. Until they actually fail to show up in court--don't put them behind bars when they haven't been convicted of anything.

Address the fact that you can't possibly try all these cases. The issue of felony convictions has to be looked at because all that you're doing is perpetuating an underclass by stamping the poor with that felony. There has to be a pathway into the larger society. Slapping on the felony and the cheap political rhetoric of "make this a felony, make that a felony," that's got to change. Give people a chance.

I have a lot of ideas. There has to be mandatory reporting for health care workers behind bars. As I mentioned in the book, as a social worker, we are mandated reporters when it comes to child abuse--you could lose your license for failing to report suspicion of child abuse--but not prisoner abuse. We came into contact every day with people who were presumed innocent and who were paraded before us, and we knew they had been abused by the COs.

We had to walk a fine line in there. Our own safety was at stake as well as the inmates'. That has to go. If you're mandated to report it, well, you have no choice and you report it. That would be huge in bringing down the brutality inside jails and prisons across the country. I think that correctional unions would fight that tooth and nail, but it would be a very big step forward.

ON THE question of bail, New York Mayor Bill De Blasio, after the recent killing of a police officer, came out and said that judges should be able to set bail based on "dangerousness." Also, the Board of Corrections is now deciding on these severe restrictions on visitors to Rikers. It seems that reforms are promised on the one hand and then quickly retracted with the other.

YEAH, ACTUALLY, I'm very familiar with what you're talking about because I testified about the visitor proposal that they were trying to make back in October. Then I actually authored an op-ed piece at The Crime Report about the new visitor restrictions that they are trying to get in place, as well as rolling back the reforms they made to solitary confinement.

They were also trying to place greater restrictions on packages that people receive. As you said, by the Board of Corrections' own estimate, upwards of 80 percent of the weapons that are found in jails at Rikers have been fashioned within the jails--not coming in through the visitors--and from the correctional staff who are not going to be subjected to the same rigor as these poor visitors.

I argued very strenuously against what they are proposing--which is to now start background checks on visitors. Coincidentally, I had received, and this is something that I testified about, an email from a woman whose husband had been at Otis Bantum Correctional Center for over a year waiting for trial, of course, for a speedy trial.

She and her baby went to visit him once, and she told me they only went once because they were made to wait five hours for a one-hour visit. Then when they get in to see him, she said the dogs were sniffing her throughout the one-hour visit. They're just being sniffed by dogs directly, and she was unable to feed the baby because the bottle of milk was considered contraband. She said the baby was crying and hungry. "For over six hours I could not feed this infant because that was contraband, we were being sniffed by dogs."

I said before the board that not only does the DOC need to reverse course, my point is that family visits, connections with family, has a calming effect on people.

When I worked with people on Rikers and they learned that a wife, a girlfriend, or mother was not going to visit them anymore because they were so upset by the way that they were treated, how they were criminalized, these guys would be in an emotional orbit. Now, that is a state of mind that would lead to violence. Like what the hell, I'm at the end of my rope, I can't see my wife, I'm in this hellhole.

What I argued is that these visits should be nurtured, they should be supported, facilitated because they have a calming effect on people. That if they want to reduce violence and increase safety, work at humanizing because the more you extinguish the vestiges of humanity at Rikers Island, the more inhumane it becomes. You start to make it even harder on visitors, well, you're going to get fewer and fewer visits. Just cutting people off more and more.

Their answer to everything is a bigger and bigger hammer.

Another issue is that they want packages to come in through approved third-party vendors. My argument was that they can't afford this! These are the poorest of the poor. What makes you think they'll have Amazon accounts? I said, it's outright cruel. If a family wants to send some socks or whatever to their son, they can't pack up the socks and mail them, they have to now have an Amazon account and purchase new items to have stuff sent in.

When I was at Rikers, Norman Seabrook, the president of the Correctional Officers Benevolent Association, spoke. He's been all over the news about the gangs, etc. I met so many gang members, and there's a failure to acknowledge that the culture on Rikers itself--which could easily be changed, at least I think it could be--is a huge contributing factor to the reason people join gangs to begin with.

I sat with so many inmates who said to me, "Miss Buser, I don't really want to join but the Ñetas uphold the Hispanic culture, they were all about honor" and blah blah blah. What was unspoken that we both knew is that they were terrified.

By joining a gang, you get protection. If you mess with one person, you have the whole gang. You're safer in a gang. People are driven to join not because they are inherently bad or they're gangbangers, but because they are terrified, they are petrified and they've got to survive.

I would then meet with an equal number who would then come in and say, "I want to get out because the same people would say they want me to cut someone. I don't want to do it, but if I don't do it, they're going hurt me." This happened all the time.

I was actually in a meeting when I was at Rikers with civilians about gangs, and I raised my hand and I said, "Could we have safe avenues for people to renounce their gang membership?" No questions asked, as a violence reduction strategy. Why not, if someone wants out of that gang, could they be bused to another jail on the island which is for people who no longer want to be part of it--a different type of place where they could be safe with that decision. I was told, "No. Mental health, here they go again--don't know what they're talking about." I asked a few times about it and you just get, "No, no, no."

There are so many ways to approach this, but they're simply not receptive to it. I think a lot of it stems from Norman Seabrook, and yet if you read in the book this is not a happy lot for the officers either.

Working in an inhumane place, they're not immune from it. Alcoholism--rampant. I would have to sweep up empty shards of glass by my car in the parking lot every day. I was told by a professor at Columbia that the life expectancy of a CO is 55 years. So this isn't working for them either--even though they're staunchly holding their position. It doesn't work for anyone. It's inhumane for all involved.

First published at Jacobin.