The Cuba that Castro created

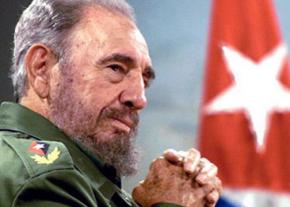

is the author of Cuba Since the Revolution of 1959: A Critical Assessment and The Politics of Che Guevara: Theory and Practice. Here, he looks at the legacy of Fidel Castro, who died on November 25, in an article written for In These Times.

AFTER A long illness that forced him to withdraw from office in July 2006, Fidel Castro died on November 25. Castro had previously survived many U.S. efforts to overthrow his government and physically eliminate him including the sponsorship of invasions, numerous assassination attempts and terrorist attacks. He held supreme political power in Cuba for more than 47 years, and even after having left high office he continued to be politically engaged for several years meeting with numerous foreign personalities and writing his Reflexiones in the Cuban Communist Party press.

Fidel was a son of Cuban-born Lina Ruz and Galician immigrant Ángel Castro, who became a wealthy sugar landlord in the island. Fidel attended a Jesuit high school, regarded as one of the best schools in Cuba. Upon entering the University of Havana Law School in 1945, he began his political life by collaborating with one of the various political gangster groups that plagued the university. As a militant university activist, Fidel participated, in 1947, in an attempt to invade the Dominican Republic to provoke an uprising against Trujillo, and in the 1948 "Bogotazo," the widespread rioting that shook the Colombian capital after the assassination of Liberal leader Eliecer Gaitán. The disorganized and chaotic nature of these failed enterprises played an important role in shaping Castro's views on political discipline and the suppression of dissident views and factions within the revolutionary movement.

He then joined the crusading Ortodoxo Party led by the charismatic senator Eduardo "Eddy" Chibás, where he became a candidate for the House of Representatives. The Ortodoxo was a democratic and progressive reform party unambiguously opposed to Communism, and focused on the elimination of the widespread political corruption in the island. It was the youth section of this party that became the main recruiting ground for Fidel Castro when he turned to the armed struggle against the newly installed military dictatorship of retired General Fulgencio Batista.

Batista took power in a coup d'état on March 10, 1952, to prevent the general election that was supposed to take place--and which he was certain to lose--on June 1 of the same year. By late 1956, a little over two years before Batista was overthrown, Castro's 26th of July Movement, named after the day of his failed armed attack in 1953, had begun to emerge as the hegemonic pole of opposition to the dictatorship. This was made possible, in part, by the collapse of Cuba's older political parties, including the Ortodoxos, and by the failure of the uprisings led by other organizations. But his hegemony among the revolutionary ranks was also the outcome of his own political talents. Castro was a canny revolutionary politician, and a master at utilizing the key elements of the prevailing democratic political ideology in the opposition to Batista to attract and broaden the support of all of Cuba's social classes. This is how he repeatedly endorsed, before the victory of the revolutionary movement, the progressive and democratic Constitution of 1940, which was widely popular. This is also how, without diminishing his political militancy, he played down the social radicalism of his 1953 History Will Absolve Me.

Fidel Castro was also a consummate tactician who instantly grasped and acted on the key issues of the moment. For example, after having been released from prison and taken refuge in Mexico in 1955, he coined the slogan "in 1956, we will be either martyrs or free men." He knew that with this pledge he was bound to return to Cuba on that year, even if he was not militarily ready, or run the immense risk of losing credibility. Nevertheless, he decided this was necessary to differentiate his group from his armed competitors and to revive the popular political consciousness particularly among the youth, which had become so eroded by disillusion. He kept his word, landing in Cuba with 81 other men aboard the Granma in the early part of December 1956, which significantly increased his prestige.

FIDEL CASTRO'S absolute defeat of Batista's Army opened the way for the transformation of a multi-class democratic political revolution into a social revolution. In the first couple of years after the revolution, Fidel Castro cemented his overwhelming popular support with a radical redistribution of wealth that later turned into a wholesale nationalization of the economy that included even the smallest retail establishments. This highly bureaucratic economy led to very poor performance which was greatly aggravated by the criminal economic blockade that the United States imposed on Cuba as early as 1960. It was the massive Soviet aid that Cuba received that made it possible for the regime to maintain an austere standard of living that guaranteed the satisfaction of the most basic needs of the population, especially education and health. Equally important in buttressing popular support for the Castro regime was the revival of a popular anti-imperialism that had been dormant in the island since the 1930s.

Fidel Castro's government channeled popular support into popular mobilization. This was the Cuban government's most significant contribution to the international Communist tradition. But while encouraging popular participation, Fidel prevented popular democratic control, and kept as much personal political command as he could.

Under his leadership, the Cuban one-party state was established in the early 1960s and was legally sanctioned by the Constitution adopted in 1976. The ruling Communist Party uses the "mass organizations" as transmission belts for the party's "orientations." When these "mass organizations" were originally established in 1960, all the previously existing independent organizations that could have potentially competed with the official institutions were eliminated. These included the "sociedades de color," which for a long time had been the bedrock of Black organizational life in Cuba, numerous women's organizations mostly engaged in welfare activities, and the trade unions which became incorporated into the state apparatus after a thorough purge of all dissenting views.

Fidel Castro's personal control from the top was a major source of economic irrationality and waste. The overall balance of his personal interventions in economic affairs is quite negative. These ranged from the economically disastrous campaign for a 10-million-ton sugar crop in 1970, which failed to achieve its sugar goals and greatly disrupted the rest of the economy, to the economic incoherence and intrusive micro-management of his "Battle of Ideas" shortly before he left office.

A MAJOR feature of Fidel Castro's 47-year-old rule was his manipulation of popular support. This was especially evident in the first two years of the revolution (1959-60) during which he never revealed even to his supporters where he intended to go politically. The systematic censorship that his government established since 1960 is intrinsic to the manipulative politics of his regime, and has continued under Raúl Castro. The mass media, in compliance with the "orientations" of the Ideological Department of the Cuban Communist Party, publishes only the news that satisfies the political needs of the government. Censorship is most striking in radio and television, which is under the aegis of the ICRT (Instituto Cubano de Radio y Television--Cuban Institute of Radio and Television), an institution despised by many artists and intellectuals for its censorious and arbitrary practices. The systematic absence of transparency in the operations of the Cuban government has continued under Raúl Castro's rule. A clear example is the sudden removal, in 2009, of two top political leaders, Foreign Minister Felipe Pérez Roque and Vice President Carlos Lage, without a full explanation from the government for the decision. Since then a video detailing the government's version of that event has been produced but shown only to selected audiences of leaders and cadres of the Cuban Communist Party. Censorship and the lack of transparency has at times turned into outright mendacity, like in the case of Fidel Castro's repeated denials of physical mistreatment in Cuban prisons, in the face of its well documented existence by several independent human rights organizations.

Fidel Castro created a political system that does not hesitate to use repression, and not only against class enemies, to cement its power. It is a system that has recurred to police and administrative methods to settle political conflict. It has used the legal system in an arbitrary manner to stifle political dissent and opposition. Among the laws it has invoked to achieve this aim are those punishing enemy propaganda, contempt for authority (desacato), rebellion, acts against state security, clandestine printing, distribution of false news, pre-criminal social dangerousness, illicit associations, meetings and demonstrations, resistance, defamation and libel. In 2006, Fidel Castro admitted that at one time there had been 15,000 political prisoners in Cuba, although in 1967 he cited the figure of 20,000.

FOR MANY Latin Americans and other people in the Third World it is not the establishment of Communism in Cuba that elicited their sympathy for the Cuban leader. It was rather his outright challenge to the North American empire and his dogged persistence in that effort, not only affirming Cuban independence but also supporting and sponsoring movements abroad against the local ruling classes and the U.S. empire. Fidel's government paid the price for this with Washington's sponsorship of military invasions, assassination attempts and terror campaigns, in addition to the longstanding economic blockade of the island. Standing up to the North American Goliath was not only a matter of overcoming a vastly superior power, but also the arrogance and racism of the powerful northern neighbor. As the historian Louis A. Perez has noted, Washington often saw Cubans as children who had to be taught how to behave.

Yet there are numerous misconceptions on the left about Cuban foreign policy. While it is true that Fidel Castro maintained his opposition to the U.S. empire to his last breath, his Cuban foreign policy, especially after the late 1960s, was moved more by the defense of Cuban state interests as defined by him and by his alliance with the USSR than by the pursuit of anti-capitalist revolution as such. Because the Soviet Union regarded Latin America as part of the U.S. sphere of influence, it applied strong political and economic pressure on Cuba to play down its open support for guerrilla warfare in Latin America. By the late 1960s, the USSR succeeded in this effort and that is why in the 1970s Cuba turned to Africa with a vigor that came from knowing that its policies in that continent were strategically more compatible with Soviet interests, in spite of their many tactical disagreements. This strategic alliance with the USSR helps to explain why Cuba's Africa policy had quite different implications for Angola and South African apartheid where it was generally on the left, than for the Horn of Africa, where it was not. In this part of the continent, Fidel Castro's government supported a "leftist" bloody dictatorship in Ethiopia and indirectly helped that government in its efforts to suppress Eritrean independence. The single most important factor explaining Cuba's policy in that area was that the new Ethiopian government had taken the side of the Soviets in the Cold War. It was for the same reasons that Fidel Castro, to the great surprise and disappointment of the Cuban people, supported the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968, although it was clear that Castro's political dislike for Dubcek's liberal policies played an important role in his decision to support the Soviet action. Fidel Castro also supported, at least implicitly, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, although he did it with much discomfort and in a low-key manner because, as it happened, Cuba had just assumed the leadership of the Non-Aligned Movement, the great majority of whose members strongly opposed the Soviet intervention.

As a general rule, Fidel Castro's Cuba has, even in the first stages of its foreign policy in the early 1960s, refrained from supporting revolutionary movements against governments that had good relations with Havana and rejected U.S. policy towards the island, independently of the ideological coloration of those governments. The most paradigmatic cases of the "reasons of state" approach of Cuban foreign policy are the very amicable relations that Cuba maintained with the Mexico of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) and with Franco's Spain. It is also worth noting that in various Latin American countries such as Guatemala, El Salvador and Venezuela, Fidel Castro's government favored some guerrilla and opposition movements and opposed others depending on the degree to which they were willing to support Cuba's policies.

THE ESTABLISHMENT of a Soviet-type regime in Cuba cannot be explained on the basis of generalizations about underdevelopment, dictatorship and imperialism, which have been applied to the whole of Latin America. The single most important factor that explains the uniqueness of Cuba's development is the political leadership of Fidel Castro that made a major difference in the triumph against Batista and in determining the course taken by the Cuban Revolution after it came to power. In turn, Fidel Castro's role was made possible by the particular socio-economic and political make-up of the Cuba of the late 1950s. This included the existence of economically substantial but politically weak classes--capitalist, middle and working class; a professional and in many ways mercenary army whose leadership had weak ties with the economically powerful classes; and a considerably decayed system of traditional political parties.

Castro's legacy, however, has become uncertain ever since the collapse of the USSR. Under Raúl Castro, the government, particularly after the sixth Communist Party congress in 2011, promised significant changes in the Cuban economy that point in the general direction of the Sino-Vietnamese model that combines an opening to the capitalist market place with political authoritarianism. The reestablishment of diplomatic relations with the United States announced in December 2014, which Fidel Castro reluctantly endorsed some time later, is likely to facilitate this economic strategy especially in the now unlikely event that the U.S. Congress modifies or repeals the Helms Burton Act approved in 1996 (with President Clinton's consent) that made into law the U.S. economic blockade of the island. Meanwhile, corruption and inequality are growing and corroding Cuban society, contributing to an overall sense of pessimism and the desire of many, particularly young people, to leave the country at the first opportunity.

In light of a likely future state capitalist transition and the role that foreign capital and political powers such as the U.S., Brazil, Spain, Canada, Russia and China may play in it, the prospects for Cuban national sovereignty--perhaps the one unambiguously positive element of Fidel Castro's legacy--are highly uncertain.

First published at In These Times.