The question of caste

The debates about caste and class in India go back many decades, but they remain relevant today, writes in a review of a new book by Arundhati Roy.

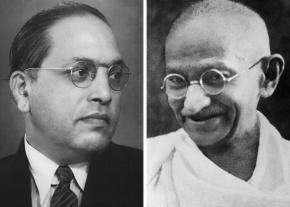

IN THE Doctor and the Saint, writer and political activist Arundhati Roy invites readers to take a new look at the "saint" M.K. Gandhi alongside a less-talked-about fighter for Indian independence and justice, Untouchable leader and intellectual Dr. B.R. Ambedkar.

This book is based on an introduction that Roy wrote in 2014 for The Annihilation of Caste--a pamphlet of a 1936 speech by Ambedkar that he was never allowed to deliver. "When I first read it, I felt as though somebody had walked into a dim room and opened the windows," writes.

After Ambedkar's speech was canceled by the Hindu reformist organization that had invited him, it was printed as a pamphlet, and though the publishing houses were modest, it sold in the millions, becoming the source of great public debate over the question of caste in India--and social discrimination on the basis of caste. Gandhi was included among the opponents to Ambedkar's views.

In The Doctor and the Saint, Roy uses this historic debate to underscore the centrality of caste in the past and present--and to take a deeper look at the myths about Gandhi.

Roy points out that the institution of caste continues today, as she outlines the brutal oppression suffered by the "scheduled castes" continues, not only in India but also in Sri Lanka, Pakistan and beyond.

CASTE OPERATES throughout the population, but is, of course, especially onerous for the scheduled castes at the bottom of the social hierarchy. Estimates put this group at 17 percent of the population.

Besides Untouchables, there are Unseeables and Unapproachables--these are the scheduled or avarna castes, known as Ati-Shudras or subhumans. Other castes are grouped into four "varnas": Brahmins (priests), Kshatriyas (soldiers),Vaishyas (traders) and Shudras (servants).

Roy explains:

Untouchables were not allowed to use the public roads that privileged castes used, they were not allowed to drink from common wells...not allowed into Hindu temples...not allowed into privileged caste schools, not permitted to cover their upper bodies, only allowed to wear certain kinds of clothes and certain kinds of jewelry.

Some castes like the Mahars...had to tie brooms to their waists to sweep away their polluted footprints, others had to hang spittoons around their necks to collect their polluted saliva. Men of the privileged castes had undisputed rights over the bodies of Untouchable women. Love is polluting. Rape is pure. In many parts of India, much of this continues to this day.

Roy gives examples of horrendous attacks and murders still carried out today, based on and reinforcing caste.

There have been some attempts at "positive discrimination," or affirmative action, so that some of the scheduled castes have made it up the social and economic hierarchy. But these efforts are extremely limited, Roy says, and have been resisted by right-wing movements that want to reinforce caste hierarchy, often leading to violence.

In spite of efforts at positive discrimination, the class structure lines up very well with the caste structure. Roy illustrates this with a list of the CEOs and billionaires who come from the upper castes. She goes on to explain the heavy overlap between lower castes and the poorest sections of the population.

Many lower caste people try to escape caste discrimination by converting to Christianity or Islam. But Hindu society treats the converts as if they are still in their hereditary caste. There are even cases of other religions in the subcontinent enforcing caste. "Though their scriptures do not sanction it," writes Roy, "elite Indian Muslims, Sikhs and Christians all practice caste discrimination. Pakistan, Bangladesh and Nepal all have their own communities of Untouchable sweepers."

Thus, caste has a basis in religion, but the system of discrimination and privilege is embedded in society at a deeper level. In fact, Hinduism was at first the name given to caste society by outsiders. The promotion of Hinduism, and later Hindutva, was a political project.

OF PARTICULAR interest to those on the left will be the section of the book looking at the Communist Party (CP) leadership's disappointing view on the politics of caste. Under the guise of focusing on class divisions, they dismiss the importance of caste discrimination.

For example, CP leader E.M.S. Namboodiripad, the former chief minister of the state of Kerala, denounced Untouchable leader Ambedkar for focusing on caste, calling it "a great blow to the freedom movement. For this led to the diversion of peoples' attention from the objective of full independence to the mundane cause of the uplift of the Harijans [Untouchables]." Harijan, or "Children of God," was the condescending name that Gandhi gave the Untouchables.

Other political formations grew out of the fight against oppression, including Ambedkar's Independent Labor Party and the Dalit Panthers in the 1970s. The Dalit Panthers descended in part from Ambedkar's politics, but also from Marxism. They used the Marithi word "Dalit," meaning oppressed or broken, to embrace all the oppressed of India. Unfortunately, the Panthers disintegrated, with some actually going over to the Hindu right.

According to Roy, the official Communist Parties became "bourgeois parties," and their rejection of the importance of caste fit in well with their pro-capitalist politics. Even the more radical Maoist parties, the Naxalites, haven't put caste at the center of their politics and haven't won significant support from the scheduled castes.

Roy helps the reader conclude that without confronting caste, there can be no working-class unity and therefore no successful struggle against capitalism. Caste division hobbles a united working-class struggle.

THE BULK of Roy's book is an analysis of Gandhi's politics in contrast to Ambedkar's.

Gandhi has become revered around the world because of his part in the campaign for India's independence and because of his commitment to nonviolence. But his first campaign in South Africa was in defense of upper-caste Indians, who were treated like Africans. Gandhi's appeal was that apartheid should treat Indians better than Africans, especially businessmen from India.

Gandhi held a racist position against the "kaffirs"--a racial slur against native Africans used in South Africa by whites, Afrikaners and some Indians like Gandhi. One of his demands was that Indians not be put in the same jail cell with Africans. Through Gandhi's life, he held a low opinion of the lower classes, castes and races--he felt they should get charity, but weren't fit to actually take part in democracy.

Gandhi also wanted to reform the British Empire and work with it, rather than get rid of it. He signed Indians up to fight on the side of the British during the Boer War in Africa and supported Britain in First and Second World Wars. "Gandhi was not trying to overwhelm or destroy a ruling structure; he simply wanted to be friends with it," writes Roy.

Funded by textile capitalist G.D. Birla, Gandhi preached collaboration between the classes. Roy quotes Gandhi, who argued:

It would be suicidal if the laborers rely on their numbers...In doing so, they would do harm to industries in the country. If, on the other hand, they take their stand on pure justice and suffer in their person to secure it, not only will they always succeed, but they will reform their masters...and both masters and men will be members of one and the same family."

Gandhi's attitude toward the scheduled castes was one of the main bones of contention with Ambedkar. Ambedkar proposed that the scheduled castes have a separate electorate so they could elect their own representatives and also be part of the general electorate.

Gandhi opposed this as "divisive." Gandhi was for incorporating Untouchables into the Hindu body politic by allowing them to worship at Hindu temples, but otherwise leaving the caste system intact. Other changes in the treatment of Untouchables would be left to the good will of the privileged castes.

Gandhi only came around to the idea that it was acceptable for people from different castes to share meals toward the end of his life. For Gandhi, the caste system was necessary and an integral part of Hinduism. For Ambedkar, it needed to be abolished.

Ambedkar tried to support Gandhi, but broke with him on the issue of caste. His politics had a radical core--self-determination for the scheduled castes and abolition of the caste system, as well as for true equality generally.

But he often sought these aims through reformist methods. For example, he was part of the commission to design the Indian constitution, but quit when it became clear that it wasn't going to achieve his goals. He organized independent political parties in support of the Dalits.

Ambedkar's analysis of the struggle for independence was right on point. Referring to the Indian National Congress, the main representative of the nationalist movement, he wrote: "The question of whether the Congress is fighting for freedom has very little importance as compared to the question of for whose freedom is the Congress fighting."

Replying to Gandhi, who questioned his sharp criticism of the Congress, Ambedkar argued in 1931, "No Untouchable worth the name will be proud of this land."

In contrasting Gandhi and Ambedkar, Roy doesn't lionize Ambedkar. But she points out the weaknesses and betrayals in the politics of the "saint"--and points out that that even in Gandhi's time, there was a political alternative.

The Doctor and the Saint provides important lessons about the need to fully incorporate the fight against oppression into the fight to abolish capitalism.