The American way of tearing families apart

, author of When the Welfare People Came: Race and Class in the US Child Protection System, looks at the many U.S. policies — past and present — that have separated children from their parents.

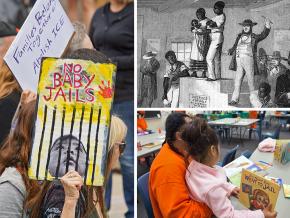

THE NATIONAL outrage over the Trump administration’s “zero tolerance” policy of separating refugee and migrant children from their parents has resulted in much greater awareness of the traumatic effects of policies that tear apart families.

Journalists digested and highlighted information long known to clinicians and social workers about the effects of removing children from their parents on the children’s short- and long-term development and mental health. One Washington Post article described some of the research:

Their heart rate goes up. Their body releases a flood of stress hormones such as cortisol and adrenaline. Those stress hormones can start killing off dendrites — the little branches in brain cells that transmit messages. In time, the stress can start killing off neurons and — especially in young children — wreaking dramatic and long-term damage, both psychologically and to the physical structure of the brain.

“The effect is catastrophic,” said Charles Nelson, a pediatrics professor at Harvard Medical School. “There’s so much research on this that if people paid attention at all to the science, they would never do this.”

The left is welcoming the surge of resistance to this latest manifestation of Trump’s cruel xenophobia. It’s also important, however, to use this moment of heightened awareness of the humanitarian crisis at the border to educate more people about the fact that the horrors of family separation aren’t unique to imprisoning refugee and migrant children.

Indeed, many politicians have declared in recent days that Trump’s zero-tolerance policy is alien to the American experience.

Republican Sen. John McCain said that separating immigrant families was “contrary to principles and values upon which our nation was founded.” Democratic Rep. Elijah Cummings declared: “[W]e all should be able to agree that in the United States of America, we will not intentionally separate children from their parents. We will not do that. We are better than that. We are so much better.”

The outrage from both sides of the political mainstream is entirely justified, but the suggestion that this policy is unprecedented in the American tradition is — like most expressions of “American exceptionalism” — simply false.

WHETHER THROUGH direct government action or nonfeasance, or through the state-sanctioned actions of powerful private actors, the purposeful separation of parents and children has a long history in the U.S. — most often linked to racial oppression or oppression based on national origin or religion.

Under slavery, the slaveholder had the legal right to separate enslaved parents and children, whenever and for whatever reason he wished — and that right was backed by the state.

An 1849 narrative by a former slave, Harry Bibb, described a mother who refused to put down her baby and climb up on the auction block, even as she was whipped.

“But the child was torn from the arms of its mother,” Bibb wrote, “amid the most heart-rending shrieks from the mother and child on the one hand, and the bitter oaths and cruel lashes from the tyrants on the other.”

For nearly a century, the Bureau of Indian Affairs removed Native American children from their families and tribes, and sent them to boarding schools to be “Americanized.” As Brian Ward wrote for SocialistWorker.org:

In these schools, the basic premise was to “Kill the Indian, save the man.” These were trade schools, which were seen as a way to assimilate Native children into U.S. society, where they could become another working-class cog to generate more capital. Children weren’t allowed to speak their language, practice their culture or have any contact with their families — if they broke these rules, they were often beaten. This was about as destructive as any massacre the tribes had faced in previous decades.

Then there was the foster boarding home model, established by wealthy reformers who feared a “dangerous class” of children of impoverished immigrants. Upon becoming wards of the state, thousands were sent west by railroad to be raised on farms and in small towns by “proper” American families.

The trainloads of children became known as the “Orphan Trains,” but most of the children sent west had living parents. The problem was that their families weren’t able to support them under the brutal conditions of the developing industrial economy.

Poor and working-class parents of children with developmental and other significant disabilities were usually given no option other than to turn them over to the state to be raised in often-horrific institutions far from their families. This policy continued in most places into the 1970s.

THIS HISTORY demonstrates that the U.S. was not, in fact, founded on the principle that the parent-child relationship is inviolate. But one doesn’t need to go back to the 19th or even 20th century to see government policies of family separation far from the border.

The most obvious example is the foster-care system, which houses approximately 400,000 U.S. children, with Black and Native American children represented in foster care at about double their percentage of the general childhood population.

Common causes of children being removed from their homes are poverty, homelessness, domestic violence perpetrated against the mother and lack of access to childcare or mental health care.

Removal rates vary from city to city, with no real correlation to child safety, nor any evidence that foster care makes children safer. On the contrary, incidence of child maltreatment may be higher in foster care — so in many cases, removal may place children in greater jeopardy than they were in at home.

What is accomplished by removal is the protection of institutions responsible for monitoring the child welfare system. By removing children from their families, these institutions are inoculated from criticism of “dropping the ball” in highly publicized cases of abuse.

As a result, the instinct is to remove a child based on speculation about what might happen at home, without necessarily considering the harm that removal might cause.

What isn’t speculative, however, is that trauma and long-term effects on development are extremely likely, as shown in the Washington Post article and other mainstream media reports spurred by Trump’s border policy.

Then there are the ways that policies of mass incarceration — set into fast motion in the final decades of the 20th century — result in the coercive power of the state forcibly removing parents from children.

With the highest incarceration rate in the world, the U.S. had, as of 2010, 2.7 million children with one or more parents who was incarcerated.

That’s one in 28 kids, up from one in 125 a quarter century earlier. And of course, as is the case with foster care, these policies of separation are disproportionately deployed against families of color.

Sometimes, the U.S. government hasn’t aided and abetted the separation of children from their parents through its actions, but through its inactions.

After the catastrophic incompetence of the federal government’s response to the disaster in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina in 2005, and with recovery planning efforts deliberately targeting affluent areas first at the expense of many poor, Black neighborhoods, about 100,000 New Orleans residents were separated from their families.

Many children were sent to stay with relatives, not only because their homes were inundated, but also because their schools failed to reopen as part of the city’s privatization scheme.

Other parents left their kids in the care of relatives in New Orleans because the only way they could earn money to support their children was to leave the city and seek work elsewhere.

There are anecdotal reports that many families in Puerto Rico are experiencing a similar pattern of separation following Hurricane Maria. The distinction between policies deliberately separating families and policies that have the effect of separating families is unlikely to mean much to the families affected.

The notion that the separation of families occurring at the border is unique and unprecedented is clearly incorrect — but this isn’t to say that Trump’s policy should be accepted in the way that mass incarceration and the foster care and adoption industry are largely accepted.

On the contrary, what’s happening to migrant children is just as unacceptable as people like John McCain and Elijah Cummings say, and resistance to this atrocity should continue.

But we should extend the principle that families should not be separated to other contexts — and to try to reverse the processes by which the horrors of mass incarceration and the foster care industry long ago became normalized.