A masterpiece made in prison

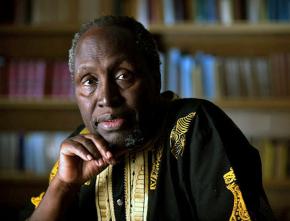

reviews a memoir by the novelist Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o that describes how he wrote the famous social protest novel Devil on the Cross while a political prisoner.

IN WRESTLING with the Devil: A Prison Memoir, Kenyan author Ngũgĩi wa Thiong’o recounts his experience as a political prisoner under the regime of President Jomo Kenyatta in the 1970s.

Ngũgĩ’s fascinating account of his detention without charges at Kamiti Maximum Security Prison from December 1977 to December 1978 centers on his chosen method of resistance against the dehumanizing conditions: He wrote a landmark novel critiquing capitalism, imperialism, sexism and neocolonialism.

The novel, titled Devil on the Cross, was composed by Ngũgĩ in his cell on toilet paper.

Wrestling with the Devil is the fourth in a series of memoirs by Ngũgĩ. It begins with his detention order, which offers only “the preservation of public security” as a rationale for his imprisonment. He relives, with a mixture of horror and incredulity, the humiliation of having his home raided.

Armed intelligence officers, known as the Special Branch, paid especially close attention to Ngũgĩ’s book collection:

Their grim, determined faces lit up only a little whenever they pounced on any book or pamphlet bearing the names of Marx, Engels or Lenin. I tried to lift the weight of the silence in the room by remarking that if Lenin, Marx or Engels were all they were after, I could save them much time and energy by showing them the shelves where these dangerous three were hiding. The leader of the book-raiding squad was not amused.

The Special Branch raiders were also very concerned about the pile of copies of Ngũgĩ’s play Ngaahika Ndeenda (translated as I Will Marry When I Want).

The play was seen as a threat to the Kenyatta government, especially because its performances were composed entirely of workers and peasants from Kamiriithu village. Ngũgĩ envisioned an Indigenous-led theater that would break free from “the general bourgeois education system” by encouraging audience participation.

After ransacking his home library, the Special Branch took Ngũgĩ into custody without allowing him to speak to his pregnant wife. He reflected on this surreal event: “I couldn’t help musing over the fact that the police squadron was armed to the teeth to abduct a writer whose only acts of violent resistance were safely between the hard and soft covers of books.”

WHY WOULD a neocolonial regime like Kenyatta’s target writers and intellectuals? Ngũgĩ offers a perceptive response:

[D]etention and imprisonment more immediately mean the physical removal of progressive intellectuals from the people’s organized struggles. Ideally, the authorities would like to put the whole community of struggling millions behind bars, as the British colonial authorities once tried to do with Kenyan people during the State of Emergency, but this would mean incarcerating labor, the true source of national wealth. What then would be left to loot?

By targeting a handful of intellectuals and writers committed to the people’s struggles, those in power can strike fear and uncertainty into the masses. Once the political prisoner is behind bars, the Kenyatta government had a whole range of tactics to undermine prisoner solidarity, sanity and hope.

From the first moment of Ngũgĩ’s detention, he was no longer known by his name. “K6,77 was my new identity,” he writes.

He was immediately placed in “internal segregation,” which meant that he wasn’t allowed any interaction with other political prisoners for the first several weeks of his imprisonment. For the early months of his time in Kamiti prison, Ngũgĩ had no access to newspapers, magazines or other news sources.

One of the only individuals Ngũgĩ was allowed to interact with at the beginning of his imprisonment was a prison chaplain. The chaplain would arrive at his cell “staggering under the weight of two huge Bibles [one in English and one in Gikuyu]...plus a bundle of revivalist tracts from the American-millionaire-rich evangelical missions.”

Ngũgĩ was not impressed with the chaplain’s prosperity gospel and frequent attacks on the Kenya Land and Freedom Party — the Kenyan soldiers who fought the British for their liberation — whom the chaplain dismissively referred to as “the Mau Mau.”

A more nuanced tactic used by the Kenyatta regime to neutralize the influence of the political prisoners involved turning prisoners’ families against them. By encouraging the family to “talk some sense into” the prisoner, the government could further isolate them and make real change in Kenya seem more unlikely.

If one’s own family did not stand beside them in the struggle for liberation, what hope can there be? Luckily for Ngũgĩ, his wife remained committed to him and to the struggle, finding indirect ways to let him know that she and their newborn baby were proud of his uncompromising stance.

Some of the psychological torture inflicted by the prison administration was lifted directly from the British colonial playbook. For example, political prisoners were often required to submit to chaining of the hands and feet, even in situations where the likelihood of escape was virtually nil.

Withholding medical treatment was also commonplace. Because Ngũgĩ refused to endure the indignity of submitting to being chained, he was denied treatment of an abscessed tooth. He witnessed other ill prisoners left to writhe in pain, unable to stand, due to the prison administration’s callous neglect.

NGUGI ASSERTS that what allowed him to maintain his sanity and optimism during this dark time in his life was his ambitious project to secretly write a novel that pointed the way toward a better future for Kenya and the world.

Writing a novel in a maximum-security prison proved incredibly difficult for Ngũgĩ, although he points out that “virtually all of the political prisoners are writing or composing something, on toilet paper mostly.”

The prison guards would provide a pen and a couple of pieces of paper to prisoners who requested it in order to write out their confessions. Unintentionally, the prison’s attempt to make the prisoners suffer was turned by prisoners like Ngũgĩ to their advantage: “[The toilet paper] was actually hard, meant to punish prisoners, but it turned out to be great writing material, really holding up to the ballpoint pen very well. What was hard for the body was hardy for writing on.”

After sketching the outline of Devil on the Cross in the margins of a Bible, Ngũgĩ embarked on his goal to write the first novel ever in the Gikuyu language. The process of writing filled his prison year with meaning and purpose: “Writing this novel has been a daily, almost hourly, assertion of my will to remain human and free despite the state’s program of animal degradation of political prisoners.”

The hero of Ngũgĩ’s novel Devil on the Cross is Wariinga, a young woman who is fired from her job in Nairobi for refusing to have an affair with her boss. After failing to find work in the capital city that is not exploitative, she decides to travel back to her small town of Ilmorog.

Along the way, she finds out about a “modern theft and robbery” competition, labeled by student activists as the “Devil’s Feast.” This feast brings together capitalists from around the world to compete in “modern theft” and to train postcolonial Kenyan businessmen in the dark arts of exploitation of labor and natural resources.

Devil on the Cross offers a pointed, sustained critique of postcolonial Kenya. Instead of providing the working class and peasants in Kenya with freedom and dignity, the nation’s independence changed the race and nationality of the exploiters, creating what Ngũgĩ calls a “colonial Lazarus.”

A character in the novel describes “the truth about the unity that exists between us and foreigners...They eat the flesh and we clean up the bones.” Unless the workers emancipate themselves from exploitation and imperialism, Ngũgĩ argues in the novel, nothing will change:

Imperialist, that’s your real name, and you are a cruel master. Why? Because you reap where you have never sown. You grab things over which you have never shed any sweat. You have appointed yourself the distributor of things which you have never helped to produce. Why? Just because you are the owner of capital.

Ngũgĩ’s Devil on the Cross is a powerful indictment of a system that attempted to crush him and the millions of Kenyans fighting for a more just society.

In its final chapters, Wrestling with the Devil becomes a suspenseful mystery story as well. In the chapter titled “Sherlock Holmes and the Strange Case of the Missing Novel,” Ngũgĩ presents the stranger-than-fiction events which led to the disappearance (and eventual reappearance) of his Devil on the Cross manuscript. That this brilliant novel was nearly lost forever is all the more reason to read it today.

Ngũgĩ reflects on the genesis of Devil on the Cross in fundamentally materialist terms:

[N]obody writes under one’s chosen conditions with one’s chosen material. Writers can only seize the time to select from material handed to them by history and by whomever and whatever is around them.”

Wrestling with the Devil is an awe-inspiring true account of the harsh conditions that gave rise to a masterpiece of social protest fiction.