Making a new date in history

SocialistWorker.org is continuing its series 1917: The View from the Streets with excerpts from a firsthand account of the revolution by socialist journalist , written for the New York Evening Post and published as a book in 1921. Along with the more famous Ten Days That Shook the World by fellow journalist John Reed, Williams' Through the Russian Revolution provides a riveting picture of the struggle to create a new society as Russian workers, soldiers, sailors and peasants began seizing control over every aspect of their daily lives.

In the excerpt below from chapter seven, Williams tells the story of the downfall of the Provisional Government and the establishment of a workers' government, from the vantage point of the nerve center of the revolution in Petrograd. SW's series on 1917 is edited by John Riddell and co-published at his website.

WHILE PETROGRAD is in a tumult of clashing patrols and contending voices, men from all over Russia come pouring into the city. They are delegates to the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets convening at Smolny. All eyes are turned towards Smolny.

Formerly a school for the daughters of the nobility, Smolny is now the center of the Soviets. It stands on the Neva, a huge stately structure, cold and grey by day. But by night, glowing with a hundred lamp-lit windows, it looms up like a great temple---a temple of Revolution. The two watch fires before its porticos, tended by long-coated soldiers, flame like altar-fires. Here are centered the hopes and prayers of untold millions of the poor and disinherited. Here they look for release from age-long suffering and tyranny. Here are wrought out for them issues of life and death.

That night I saw a laborer, gaunt, shabbily-clad, plodding down a dark street. Lifting his head suddenly he saw the massive façade of Smolny, glowing golden thru the falling snow. Pulling off his cap, he stood a moment with bared head and outstretched arms. Then crying out, "The Commune! The People! The Revolution!" he ran forward and merged with the throng streaming thru the gates.

Out of war, exile, dungeons, Siberia, come these delegates to Smolny. For years no news of old comrades. Suddenly, cries of recognition, a rush into one another's arms, a few words, a moment's embrace, then a hastening on to conferences, caucuses, endless meetings.

Smolny is now one big forum, roaring like a gigantic smithy with orators calling to arms, audiences whistling or stamping, the gavel pounding for order, the sentries grounding arms, machine-guns rumbling across the cement floors, crashing choruses of revolutionary hymns, thundering ovations for Lenin and Zinoviev as they emerge from underground.

Everything at high speed, tense and growing tenser every minute. The leading workers are dynamos of energy; sleepless, tireless, nerveless miracles of men, facing momentous questions of Revolution.

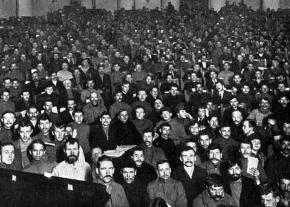

At ten-forty on this night of November 7th, opens the historic meeting so big with consequences for the future of Russia and the whole world. From their party caucuses the delegates file into the great assembly-hall. Dan, the anti-Bolshevik chairman, is on the platform ringing the bell for order and declares, "The first session of the Second Congress of Soviets is now open."

First comes the election of the governing body of the congress (the presidium). The Bolsheviks get 314 members. All other parties get 11. The old governing body steps down and the Bolshevik leaders, recently the outcasts and outlaws of Russia, take their places. The Right parties, composed largely of intelligentsia, open with an attack on credentials and orders of the day. Discussion is their forte. They delight in academic issues. They raise fine points of principle and procedure.

Then, suddenly out of the night, a rumbling shock brings the delegates to their feet, wondering. It is the boom of cannon, the cruiser Aurora firing over the Winter Palace. Dull and muffled out of the distance it comes with steady, regular rhythm, a requiem tolling the death of the old order, a salutation to the new. It is the voice of the masses thundering to the delegates the demand for "All Power to the Soviets." So the question is acutely put to the Congress: "Will you now declare the Soviets the government of Russia, and give legal basis to the new authority?"

The Intelligentsia Desert

Now comes one of the startling paradoxes of history, and one of its colossal tragedies---the refusal of the intelligentsia. Among the delegates were scores of these intellectuals. They had made the "dark people" the object of their devotion. "Going to the people" was a religion. For them they had suffered poverty, prison and exile. They had stirred the quiescent masses with revolutionary ideas, inciting them to revolt. The character and nobility of the masses had been ceaselessly extolled. In short, the intelligentsia had made a god of the people. Now the people were rising with the wrath and thunder of a god, imperious--and arbitrary. They were acting like a god.

But the intelligentsia reject a god who will not listen to them and over whom they have lost control. Straightway the intelligentsia became atheists. They disavow all faith in their former god, the people. They deny their right to rebellion.

Like Frankenstein before this monster of their own creation, the intelligentsia quail, trembling with fear, trembling with rage. It is a bastard thing, a devil, a terrible calamity, plunging Russia into chaos, "a criminal rebellion against authority." They hurl themselves against it, storming, cursing, beseeching, raving. As delegates they refuse to recognize this Revolution. They refuse to allow this Congress to declare the Soviets the government of Russia.

So futile! So impotent! They may as well refuse to recognize a tidal wave, or an erupting volcano as to refuse to recognize this Revolution. This Revolution is elemental, inexorable. It is everywhere, in the barracks, in the trenches, in the factories, in the streets. It is here in this congress, officially, in hundreds of workmen, soldier and peasant delegates. It is here unofficially in the masses crowding every inch of space, climbing up on pillars and windowsills, making the assembly hall white with fog from their close-packed steaming bodies, electric with the intensity of their feelings.

The people are here to see that their revolutionary will is done; that the congress declares the Soviets the government of Russia. On this point they are inflexible. Every attempt to becloud the issue, every effort to paralyze or evade their will evokes blasts of angry protest.

The parties of the Right have long resolutions to offer. The crowd is impatient. "No more resolutions! No more words! We want deeds! We want the Soviet!"

The intelligentsia, as usual, wish to compromise the issue by a coalition of all parties. "Only one coalition possible," is the retort. "The coalition of workers, soldiers and peasants."

Martov calls out for "a peaceful solution of the impending civil war." "Victory! Victory!--the only possible solution," is the answering cry.

The officer Kutchin tries to terrify them with the idea that the Soviets are isolated, and that the whole army is against them. "Liar! Staff!" yell the soldiers. "You speak for the staff--not the men in the trenches. We soldiers demand 'All Power to the Soviets!'"

Their will is steel. No entreaties or threats avail to break or bend it. Nothing can deflect them from their goal.

Finally stung to fury, Abramovich cries out, "We cannot remain here and be responsible for these crimes. We invite all delegates to leave this congress." With a dramatic gesture he steps from the platform and stalks towards the door. About eighty delegates rise from their seats and push their way after him.

"Let them go," cries Trotsky, "let them go! They are just so much refuse that will be swept into the garbage-heap of history."

In a storm of hoots, jeers and taunts of "Renegades! Traitors!" from the proletarians, the intelligentsia pass out of the hall and out of the Revolution. A supreme tragedy! The intelligentsia rejecting the Revolution they had helped to create, deserting the masses in the crisis of their struggle. Supreme folly, too. They do not isolate the Soviets, they only isolate themselves. Behind the Soviets are rolling up solid battalions of support.

The Soviets Proclaimed the Government

Every minute brings news of fresh conquests of the Revolution---the arrest of ministers, the seizure of the State Bank, telegraph station, telephone station, the staff headquarters. One by one the centers of power are passing into the hands of the people. The spectral authority of the old government is crumbling before the hammer strokes of the insurgents.

A commissar, breathless and mud-spattered from riding, climbs the platform to announce: "The garrison of Tsarskoye Selo for the Soviets. It stands guard at the gates of Petrograd." From another: "The Cyclists' Battalion for the Soviets. Not a single man found willing to shed the blood of his brothers." Then Krylenko, staggering up, telegram in hand: "Greetings to the Soviet from the Twelfth Army! The Soldiers' Committee is taking over the command of the Northern Front."

And finally at the end of this tumultuous night, out of this strife of tongues and clash of wills, the simple declaration: "The Provisional Government is deposed. Based upon the will of the great majority of workers, soldiers and peasants, the Congress of Soviets assumes the power. The Soviet authority will at once propose an immediate democratic peace to all nations, an immediate truce on all fronts. It will assure the free transfer of lands . . . etc."

Pandemonium! Men weeping in one another's arms. Couriers jumping up and racing away. Telegraph and telephone buzzing and humming. Autos starting off to the battle-front; aeroplanes speeding away across rivers and plains. Wireless flashing across the seas. All messengers of the great news!

The will of the revolutionary masses has triumphed. The Soviets are the government.

This historic session ends at six o'clock in the morning. The delegates, reeling from the toxin of fatigue, hollow-eyed from sleeplessness, but exultant, stumble down the stone stairs and thru the gates of Smolny. Outside it is still dark and chill, but a red dawn is breaking in the east.

Source: From chapter seven of Albert Rhys Williams, Through the Russian Revolution. (Boni and Liveright, 1921), pages 98-104.

A note on Russian dates: The Julian calendar used by Russia in 1917 ran 13 days behind the Gregorian calendar that is in general use today.