Where politics and art meet

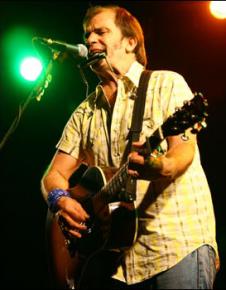

Steve Earle recently won a second Grammy for Washington Square Serenade, the latest in a string of records that have shown him to be one of America's most talented musicians and songwriters.

He's also one of the one of the most explicitly political musicians around. He is a longtime activist against the death penalty and the criminal injustice system. Earle's previous records Jerusalem and The Revolution Starts...Now stirred controversy among right wingers because of their open challenges to the U.S. "war on terror"--especially the song "John Walker's Blues," written from the point of view of the American captured during the U.S. war on Afghanistan, John Walker Lindh.

Earle spoke to Socialist Worker's on a recent tour stop in Madison, Wis.

FIRST OF all, I've read that you're a big baseball fan, so I have to ask: You're a New Yorker now, are you also a Yankees fan?

YEAH, I am, but I was all my life, even before I moved to New York. I'm one of those middle-of-the-country television Yankees fans.

The term "America's Team" was coined for the Yankees in the '50s and '60s because there were only two stadiums that were really set up for television--that was Dodger Stadium and Yankee Stadium. So you got the Dodgers or the Yankees playing on the game of the week every week. It's the only baseball I got when I was growing up. I was six years old in '61, and it was Maris and Mantle.

ONE THING that gets me about baseball is how right-wing politics has gotten more into the world of sports--"God Bless America" instead of "Take Me Out to the Ball Game" for the seventh-inning stretch, "military days" and "faith days" at the ballpark. How does all that sit with you as a baseball fan?

IT'S HARD, especially as a Yankees fan in New York City. But you have to be sensitive to the fact that 9/11 happened in New York City, and the reaction to it there. It's like when I do death penalty work, I can't lose sight of the people who are the families of victims, who have every right to their anger and their pain. We all became victims' family members on September 11.

UNTIL THEY twisted it.

RIGHT, THEY twisted it. Giuliani was politically dead until September 11.

The only thing that baseball or any other sport has to do with politics is that it's mass media, and it's big, big business. You know, the whole world is coming apart, so what on earth are they doing even worrying about steroids and drug use in baseball. I think it's horrible and ridiculous, and I think that baseball is responsible. But I feel the same way about that as I do the state the country is in.

It's not "them," it's us. We wanted to see the fucking home runs, and we were fucking okay with it, just like we were totally fucking okay--those of us who kept our jobs and managed to work--with the direction the country was going. And we can't forget that.

IT'S BEEN hard to watch Roger Clemens get grilled by Congress while they lob softballs at the baseball commissioner, Bud Selig, who presided over the whole thing.

YEAH, BUT Clemens is a dumbass. He's not very smart. He's just a typical Texas jock who totally brought this on himself. This is a guy that cheated and didn't want to admit it to his kids. It's kind of heartbreaking to watch.

YOU MENTIONED your anti-death penalty work. What drew you to that?

IT'S WEIRD, but it drew me. I wrote a song called "Billy Austin," and I was always opposed to the death penalty. I saw In Cold Blood, and then read the book--that was back in '67, and in '67, I was starting to look around a little bit.

The death penalty died of natural causes at that time in the United States. No one had been executed in Texas since '61 or '62, until the death penalty was reinstated in the '70s. There was a death penalty until the '70s, but they weren't using it, and then it became illegal, and we became more civilized.

The thing about the death penalty as it's practiced in this country is it only happens to poor people. It's always been that way. And it doesn't happen for any other reason than to make politicians appear tough on crime.

But they're not there when it happens, and they don't really know what they're doing. People that advocate the death penalty don't really know what they're advocating. They've never sat there when someone was being executed, and I have. And they don't know, they just don't know.

YOU WITNESSED the execution of Jonathan Nobles in Texas. What was that like?

IT WAS horrific, and it was life-changing. And it wasn't like the guy was innocent. He wasn't. He was guilty of a really heinous crime. But it was really obvious that you were witnessing a really, really, really unnatural act--something that isn't supposed to happen and that diminished everybody that was involved in it, probably even me. But I was asked, so I was there.

SO WHAT do you think now? New Jersey abolished the death penalty recently, and Kenneth Foster Jr. won clemency in Texas last year. It seems like there's some momentum for abolition.

YEAH, THERE is. And most of it is because of economics. There was this divide between people who were moral abolitionists, and people who were more pragmatic abolitionists in the sense that they saw wrongful convictions as a great lever.

And wrongful convictions are the main reason that we're where we're at--the main reason that executions have slowed down drastically. Just that possibility--nobody can deal with that, no matter how bloodthirsty they think they are.

I don't think that we're basically bloodthirsty people. I think we're people who live in a society where we've learned how to kill by remote control--even these wars that we're fighting. The thing about the war that we've gotten ourselves into is that everybody's kind of lost their taste for it pretty quickly.

There's nothing we can do in this one besides going in and blowing more shit up and really racking up civilian casualties. The way the war is fought now, the vast majority of the casualties are civilians, and it's been that way for a long time. And the people who became soldiers weren't necessarily people who had a choice, and that has to do with economics.

I'm not sure what's going to happen now, but some things have changed. The death penalty is falling apart, partially because people have figured out that it's just not economically feasible, and if that's why it ends, then that's fine. Whatever keeps me as a member of the democracy from going to hell is fine--I don't care why people agree, as long as we agree.

I'm a socialist in a country where there's no viable socialist party, and by viable, I mean in the sense of participating in these elections. Neither of these candidates are anywhere close to anything that I consider to be the left, but I'll vote for whichever one gets the Democratic nomination in the general election.

I'm not a Democrat. I vote outside the Democratic Party all the time. I just don't do it in the presidential elections, and I'm probably not likely to, unless something drastically changes. Things are too critical right now. It's not about lesser evilism to me. It's about survival.

YOU WERE in a performance of Howard Zinn's Voices of a People's History of the United States, where you read the last words of Joe Hill and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, two famous left-wing victims of the death penalty.

TO GET to do those two readings...I mean, Joe Hill kind of invented part of my job. I have a clay sculpture of Joe Hill that this artist walked up and handed me in San Diego when I was walking off the bus. Joe Hill obviously fascinates me.

And Bartolomeo Vanzetti--what happened to those guys is so similar to what's happening to a lot of people now. It was fear-mongering at the time, just like today.

YOU ALSO sang "This Land is Your Land" by Woody Guthrie and "Masters of War" by Bob Dylan. What did those two mean to you?

WELL, I'M a big Bob Dylan fan, but "Masters of War" is not the most effective of Dylan's political songs. It's not that I disagree with the sentiment of it, but it's kind of ham-handed. I was asked to sing it, and I got through it.

But I love "This Land." I used to go out and do only the verses that have been neatly removed--the more radical verses. That's the song I think should be sung in Yankee Stadium for the seventh-inning stretch.

I'VE BEEN having this argument with my brother--I'm a big Dylan fan, too, and he's less of one, and we've been discussing Dylan doing Cadillac SUV ads in the middle of a war in the Middle East.

YOU KNOW, what Dylan reacted to was people expecting him to do something because they expected him to do it. So possibly if people who couldn't sing and couldn't write songs at that time and in that era--and even people who could sing and write songs--didn't sit around and try to tell a 23- or 24-year-old kid what he should be doing for the rest of his life, then maybe Bob Dylan would still write political songs.

DO YOU feel that kind of pressure? There are people who want to look to you as today's Dylan or Woody Guthrie.

SURE. I'M feeling it now, because Washington Square Serenade is much less political, at least on the surface, than the last two records I made.

And I did a Chevy commercial. It was "The Revolution Starts..."--that's what they asked for. I thought it was kind of cool, and maybe I'd make a little money. My contract said they couldn't alter the lyrics--they couldn't alter what the song said.

Neil Young has been a millionaire since he was 20 years old, and I'm a huge Neil Young fan, but I'm not rich. I make an embarrassing amount of money for a socialist who does things I really love, but I'm not rich, and I had no money in the bank at all until recently. I got out of jail not only broke, but owing the IRS a half-million dollars, and I finally got that paid off last year.

So I was working. People thought I was ambitious, but I was just desperate. It's just one of those things, and I'm not sure it behooves anybody to decide what anybody else should be doing.

I don't think that artists have a responsibility to do anything for anybody. Art isn't defined by the political risks you take--it's defined by the artistic risks you take, and the personal risks that you take. Those may be political, but they can also be just the decision to make art.

I made the decision a long time ago to do this, whether I made any money or not, and I can prove that by the trail of women that I starved nearly to death. I was 31 before I ever really made more than $3,000 or $4,000 a year, so I'm really sensitive about that.

What I do, I do because of what I believe. But I don't try to hold anybody else to that standard. We don't know why people do what they do--we don't know what they do in the voting booth, and I don't think any less of somebody if they don't become politically involved. But I'll never stop.

WHILE POLITICS and art are separate, it seems to me that part of what you're good at--part of what you do--is finding a way to make the two meet.

ABSOLUTELY. I'M better at it than most people, so I feel more of a responsibility to do it. But it's none of anybody else's business, and I have to live with the results.

I had to deal with "John Walker's Blues" and the aftermath--with not getting the television bookings that I did before for awhile and all that stuff. I knew that would happen. I wrote that song with my eyes wide open, but nobody else has the right to tell me that I have to keep doing that. I'll do it, and I haven't stopped.

This record, Washington Square Serenade, is the way it is because there've been two big changes in my life. I moved to New York and I fell in love and got married, and so it's largely love songs for Allison Moorer and New York. But it's not an apolitical record. Neither was Copperhead Road, which was one of the most political records I've ever made, and nobody talks about it in those terms.

I'm perceived more as a political writer because of the political climate that I live in. Those two records, Jerusalem and The Revolution Starts...Now, are kind of part one and part two of the same record. They were made really quickly to respond to a political atmosphere.

But the main reason I'm perceived more as a political writer is the flak around writing "John Walker's Blues" and the lack of flak around writing Revolution. Certain people figured out that they were doing nothing but selling records for me by raising hell about it, so they became very, very quiet.

THAT STRUCK me about Jerusalem. You got all the flak for "John Walker's Blues," but the first three songs on the album--"Ashes to Ashes," "Amerika vs. 6.0 (The Best We Can Do)" and "Conspiracy Theory"--are much more inflammatory, at least from the point of view of the people that gave you that flak.

WELL, THE right wing press wouldn't understand what "Ashes to Ashes" is about. They're dumber than a bag of hammers, that's the deal.

I didn't write "John Walker's Blues" because it was inflammatory, I wrote it because I couldn't not write it. I remember telling some friends of mine that I was going to write that song, and they thought I was crazy. They were afraid I was going to get hurt. But I wrote it because I have a son exactly the same age as John Walker Lindh. That's my personal connection to it, which there has to be.

I've written very few songs that are really rhetoric. "F the CC" is pure, old-fashioned rhetoric. The character speaking is me, and I don't do that very often. "John Walker's Blues" is John Walker Lindh talking, or somebody who I based on John Walker Lindh. "Ashes to Ashes" is stuff I believe, but through this semi-Biblical-sounding narrator that I've stumbled across in the last four or five years.

AS BOTH a musician and political activist who wants to see things change, what role do you think music plays in the struggle for political change and changing people's ideas?

WELL, IT can just be entertaining the troops. I was in Quebec when the Mohawks barricaded themselves into their reservation 20 years ago, and I went up there just to play for people who had been cooped up in there for awhile.

The same thing happens sometimes at death penalty events. Sometimes, it's preaching to the choir--you're just there to provide entertainment for people who have decided to take time out from their lives and get out there on the street.

Then there's also the fact that ideas can sometimes be consumed when they're set to a melody in a way that they can't when they're written down or being shouted from a street corner.

I believe that music helped stop the Vietnam War. I was there--I grew up during that war. My father heard Joan Baez sing "Amazing Grace" in the film Woodstock, and he knew her as an Al Capp character--there was a character called "Joany Phony" based on Joan Baez in Lil' Abner.

That's what he knew about her, and I watched him change during that war. He supported it because it never occurred to him not to support it--he was an American and worked for the federal government. But the war dragged on and on, and made less and less sense to him, and his boys got to be draft age.

That's different now, because in this war, they don't need a draft, and that's dulled the resistance to it. They don't need a draft because there are plenty of people who aren't working, and don't have any choice but to join the Army.

HERE WE are, five years into the war in Iraq, and public opinion has turned against it, yet if you look at it on the ground, there's not a big antiwar movement that reflects the level of opposition to it. Why do you think that is?

I THINK some of it is that people are really, genuinely afraid. I don't think that anyone believed that COINTELPRO was possible when it was initiated during the Vietnam War, and I think now people take it for granted that it's possible. I think that this government that's in power right now has names and films of everybody that got out there during the first couple years of the war.

The Vietnam War didn't stop because I was opposed to it. My dad became opposed to it--that's why it stopped. And those of us who got out there from the beginning were a part of my father becoming opposed to the war. Those things add up.

I think there are two main differences that have affected the momentum of this antiwar movement. Number one, don't ever forget that this was the largest antiwar movement that was mounted before a shot was even fucking fired--you've got to keep that in mind. The other part of it is there's no draft, so you don't have a bunch of young, white males out there trying to save their own asses--and it would be women now, too.

And I think during Vietnam, there was the intersection between the civil rights movement and the antiwar movement. You know, the right wing said about Martin Luther King, "He's a communist, now he's talking against the war," but the war was already unpopular by that time.

Segregation was dying, King was finishing it off and he was against the war. I think he managed to call attention to the fact that it was poor people who went and fought and died in the war. Those two things converging created a lot of momentum.

YOU SAID that on the surface, Washington Square Serenade is less political than some of your other work. But a song like "City of Immigrants" in today's anti-immigrant context is certainly political.

THAT WAS one of the last things I wrote for the album, and I wrote it because it's one of the reasons I live in New York. It really helps me at this point to be reminded--not that I'm going to forget--that you're right about things sometimes. The city was built by immigrants, and the whole anti-immigration thing is a distraction--it's a red herring, and it always has been. When it was introduced in Germany in the 1930s, it was a red herring, and it still is today.

They're trying to tell us that our jobs are being taken by people coming to this country when what's really happening is our jobs are being shipped overseas.

I HAVE to say, it was nice to see "P.S. Fuck Lou Dobbs" at the end of the liner notes.

YEAH, I had to stick that in there.

IN THE songs "Jerusalem" and "Rich Man's War," you put the question of Palestine right in the middle of the way you were thinking about the Middle East. Why'd you feel it was important to do that?

THE PLACE that we call Israel was called Palestine for a couple of thousand years since it was last called Israel. I don't believe that Israel doesn't have a right to exist, but I don't believe it has a right to exist at all costs, and I don't believe it has a right to exist artificially at the cost of people who have lived there for a long time.

THE SONG "Jerusalem" is hopeful. You hear the drums of war but maintain your belief in the possibility of a peaceful, secular solution.

I JUST think if you start at the worst part of a problem, then everything else is just going to get worse.

I'm a really bad Marxist when it comes to the question of spirituality. I believe in God, although I'm not a Christian, and I'm not a Jew, and I'm not a Muslim. The term Judeo-Christian offends me because it's intentionally exclusive of Islam, and that's one of the reasons we're in the position that we're in.

I just believe that there's a God, it ain't me, and that's as far as I've gotten. Godlike behavior--you know, behaving like we're a higher power, a country that's destined to rule the world--offends me. It's happened before. People in the Middle East have seen it before from Europeans, and now they're seeing it from us.

SO WHAT do you think of the argument that maybe the war was a bad idea, but now we have to stay with it to prevent bloodshed?

WHENEVER WE pull out, people are going to die. People died before we got there, but it was certainly in a lot smaller numbers than are dying now.

The average person, whether he was Shia or Sunni, didn't have any more contact with Saddam Hussein than the average American has with George Bush, so for most Iraqis, we're the ones who fucked up their country. We've destroyed it, and we should have to fix that. We should have to leave and pay for repairing it.

I WANT to ask you about the song "Red is the Color" on your new record. Maybe I'm reading into it, but the chord it struck in me was an expression of the anger and frustration that exists in this country after decades of attacks on the poor to benefit the rich. Did I get that wrong?

NO, YOU didn't get it completely wrong. The point of a song like that is not to sit around and analyze it too much. It's totally okay for you to feel that way about it.

I'm not going to tell you that you're right, and I'm not going to tell you that you're wrong. I write stuff that's pretty literal. So when I write stuff that makes you ask me those questions, I'm writing it so you ask those questions, not so that I can give you answers.

IN 2004, John Kerry tried to get elected by saying he wasn't Bush, even though he stood for a lot of the same things. But this election seems like a different animal. Although I'm not at all convinced they actually mean it, both Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama are playing more to people's aspirations, rather than their fears.

I THINK that's true. Look, we have a shot to elect a Democratic president, and I believe with all my heart that a Democrat is better for this country than a Republican president is. I believe that the damage that's been done over the last eight years is real, and I know for a fact that neither John Kerry nor Al Gore would have appointed these judges. I know that, and so I'll take that.

But I think it's really about us. If Hillary Clinton is elected, then I'll be out there trying to hold her to her promise of health care for every American the day after she takes office. If Barack Obama is elected, I'll be out there January 21st, trying to hold him to his promise of getting out of Iraq immediately.

They may promise it, but we have the responsibility to hold them to their promises, and there are ways that we can do that.

We're not powerless, and we never have been. We have to take responsibility for our own actions. The very same people who stopped the Vietnam War went to sleep and let things slide back, and now we're paying for it.

If we want a different future, we have to stay involved all the time. It would be hopeful, but electing Hillary Clinton or Barack Obama by itself won't change that much. Change is hard, and if you don't hold their feet to the fire and make them do the right thing, then they won't do the right thing.