Storm clouds over Britain

outlines the depth of the economic crisis in Britain and the challenges it raises for the British left.

WHEN METEOROLOGISTS in Britain announced that August 2008 was one of the wettest on record, it was all too easy to draw comparisons between the storm clouds overhead and the gloomy forecast for the economy.

The global credit crunch has taken a particularly heavy toll on the British housing market, with estate agents reporting an average of only one sale a week through much of the summer--the lowest numbers since records began in 1978. Buyers are struggling to obtain mortgages in a financial system driven to the brink of collapse by the fallout from the sub-prime mortgage crisis in the U.S.

Meanwhile, rising unemployment and high inflation have left British workers facing rapidly deteriorating living standards. Fuel and heating bills are up by as much as 50 percent, and prices of basic foodstuffs such as eggs have risen by a third. The resulting collapse in consumer confidence has hit retail sales hard, meaning more job losses in the service sector. As if all that weren't enough, the British pound is weaker than it has been in years.

Britain's Finance Minister Alistair Darling expressed the panic in government circles when he told the Guardian newspaper that the country was facing its worst economic situation in 60 years.

Darling's prognosis was confirmed on September 2, when the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) announced that Britain would be the first of the world's major industrialized economies to meet the official criteria for recession--two quarters of negative economic growth--by the end of the year.

Needless to say, the New Labour government's response to the crisis has been to shift the financial burden onto the backs of working people and the poor.

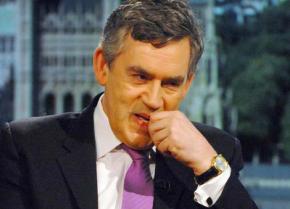

Despite public pressure from union leaders and some of his own MPs, Prime Minister Gordon Brown has ruled out a windfall tax on the mega-profits of the energy corporations and has continued to stand firm in his demands for a pay freeze among public sector employees. These workers are being offered raises of just 2 percent--less than half of the rate of inflation, and therefore effectively a 2 to 3 percent pay cut.

Even the few measures Brown has proposed to deal with the housing crisis look more like desperate stopgaps than serious solutions. The announcement of a Stamp Duty "holiday" for first-time homebuyers was widely ridiculed by experts, with many noting that the savings--about £1,500 ($2,650) on an average home--would be wiped out within a month at the current rate of decline in housing prices.

All of this has further damaged Brown's sagging popularity. Most media commentators now take it for granted that the Conservative Party--re-branded and confident under new leader David Cameron--will win a landslide victory in the 2010 general election after more than a decade in the political wilderness.

Within the Labour Party, several of Brown's rivals have begun to jockey for position in the eventuality that the embattled prime minister doesn't even last until 2010. None of these would-be challengers offers any real alternative to the governing neoliberal consensus--the frontrunner, Foreign Secretary David Miliband, took the lead in attempts to isolate and threaten Russia in the aftermath of the Georgia crisis.

FACED WITH plummeting living standards for working-class families, the British labor movement has begun to show signs of life after years of dormancy. Public-sector unions in particular have pledged to fight the wage freeze and campaign for pay increases in line with skyrocketing inflation.

Earlier in the summer, half a million local government workers in the Unison and Unite unions struck for two days in protest at below-inflation pay offers. In truth, however, the big strikes in July were tentative first steps, rather than a full-blown challenge to the government.

Now, however, certain sectors of the labor movement are pushing for more determined action. At the Trade Union Congress (TUC) annual conference in early September, union leaders and delegates expressed outrage that Gordon Brown had rejected windfall taxes on the energy corporations, and called for national protests against the wage freeze.

Speaking to the BBC, Alan Carr of the University and College Union said, "Brown should implement some radical policies...There was a feeling when Brown came in that he was substantially to the left of Blair. There isn't that feeling now." Rob Mackie of the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) agreed, stating, "The problem is that Gordon Brown and his colleagues are going away from what Labour is meant to be all about."

The conference nevertheless rejected calls from more militant unions representing prison guards, firefighters and railway workers for a public-sector general strike to win better wages and restore some of the rights--such as secondary picketing and the right to strike--that British workers lost under Prime Ministers Margaret Thatcher and Tony Blair.

The prospects for an electoral challenge to New Labour seem equally unclear. The once-promising Respect Coalition, which emerged as a serious left-wing force during protests against the war in Iraq and elected a number of local councilors as well as MP George Galloway, underwent an acrimonious split last year, and has since suffered from the defection of a number of its councilors.

The remnants of Respect hope to consolidate and perhaps extend their local bases of strength in Birmingham and London at the next elections, and the Green Party also seems poised to make modest gains in Brighton and elsewhere.

But the British left faces a serious situation. Despite the gravity of the economic crisis and the potential for increased working-class struggle, there are no guarantees that anger will flow into progressive channels.

Aided and abetted by mainstream politicians, conservative newspapers are doing everything in their power to blame crime, poverty and unemployment on Britain's immigrant population. The fascist British National Party (BNP) performed well in local elections in May, and could be set to win its first MP in the next general elections.

More than a decade of New Labour betrayals have left British workers disillusioned with their traditional party, and opened up a space for a left-wing alternative to the neoliberal agenda of Blair, Brown and the whole ruling establishment. The challenge for the British left will be to demonstrate leadership in the coming struggles over low wages and deepening inequality, while putting forward a vision of a society that puts human needs above the profits of the corporations.