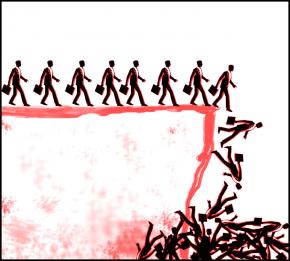

The Republican march toward oblivion

The Republican Party is hoping its screeds against "big government" will catch fire as patience with Obama's attempts to fix the crisis runs out. But that strategy may not work out the way the GOP hopes.

PERHAPS ALL we need to know about modern conservatism and its party, the Republicans, was captured in Louisiana Gov. Bobby Jindal's nationally televised response to President Barack Obama's February 24 address to a joint session of Congress.

While Obama made one of the most forceful appeals in generations for government action to address economic crisis and declining working-class living standards, Jindal centered his response on a folksy story about government bungling during the Hurricane Katrina disaster in 2005.

As he told the story, he and Jefferson Parish Sheriff Harry Lee bravely risked arrest to back down boneheaded government bureaucrats who were refusing permission for private-citizen boaters to rescue hurricane survivors.

It only took a day or two for liberal bloggers, and then the mainstream media, to show that Jindal's story was not only inaccurate, but most likely a fish story. Later, his press office had to admit that the incident he described never really happened. Every subsequent attempt that Jindal's office made to explain away the governor's tall tale just ended up making him look like an even bigger putz than he did during the speech itself.

It's hard to figure what Jindal was thinking when, in the age of Google, it would take only five minutes of clicking to discover that his story was phony. But it also illustrated the through-the-looking glass take on the world that conservatives have today.

David Brooks, the conservative New York Times columnist, scathingly reviewed the content of Jindal's speech on the PBS NewsHour with Jim Lehrer: "To come up in this moment in history with a stale, 'Government is the problem, you can't trust the federal government,' is just a disaster for the Republican Party. It's not where the country is, it's not where the future of the country is."

No wonder opinion polls placed Obama's popularity around 67 percent, while the Republicans in Congress wallow somewhere in the 30s. Obama has staked his presidency on a break with the conservative-dominated politics of the last generation. So far, he has had support from a business elite that's depending on Washington to save its skin.

The Obama administration inherited a mound of crises that are the legacy of decades of neoliberal economic policies and the position of the U.S. as the world's only superpower following the Cold War. Given this, the sense has grown, even among business circles and their political representatives in Washington, that laissez-faire politics are in need of an overhaul.

The challenge for the elites that have benefited so much from the neoliberal era is to support a change in U.S. politics that will address the parts of these crises that impinge on their ability to reap profit and power, while containing popular demands for reforms to health care, workplace rights or military spending that would challenge them.

That's where the Democratic Party has proven its usefulness to the people who run U.S. society.

All things being equal, big business prefers the Republicans, whose generally open pro-business stances aren't usually balanced against appeals to labor or the poor.

But the current Republican Party--saddled with responsibility for unpopular policies, mired in corruption and having demonstrated its incompetence in managing the affairs of state--has run its course as a vehicle for carrying out, and winning support for, big business' agenda.

In the language of Madison Avenue, which every pundit seems to have adopted these days, the Republican "brand" is damaged. And business knows when it's time to pull a bad brand off the shelf.

JUST HOW long the Republicans will stay off the shelf--whether "brand Obama" can replace them--is a question that will determine mainstream American politics over the next period, and maybe the next generation. As Bloomberg News put it on March 1:

By shifting the focus of government policy away from upper- income Americans and targeting the vast numbers who consider themselves middle-class, Obama's proposals may yield dividends for the Democratic Party. Just as Franklin Roosevelt used the New Deal to create a loyal voter base that endured for four decades, Obama's approach to fixing the economy offers the president an opportunity to recast political allegiances among swing voters.

Even though Obama's proposals fall far short of the "class warfare" and "socialism" that conservatives accuse him of, they are enough in synch with popular sentiment to suggest that he could succeed in "recasting political allegiances."

The Republicans, in response, have decided on a strategy of full-scale opposition to Obama's economic agenda without really offering anything credible as an alternative. The Republicans are banking on the two-party system's in-built tendency to make every election a negative referendum on the party in power--in essence, to give the electorate the chance to "throw the bums out" in 2010 and 2012, rather than make a positive endorsement of the party out of power.

Given the current crisis, it's a good bet that economic conditions are going to be worse for ordinary Americans through most of Obama's four years. The GOP is hoping that as conditions worsen, its screeds against "big government" will catch fire as popular patience with Obama's attempts to fix the crisis runs out. While this isn't a crazy strategy--in fact, it's the only one they have--it may not work the way the Republicans hope.

For one thing, as long as Obama is seen as "trying" to address concerns of ordinary Americans, he will continue to get some benefit of the doubt from the public. If the GOP thinks that simply railing against a "big government" that is providing unemployment benefits, health care and jobs to the unemployed will endear it to working people, they're even dumber than Jindal made them look.

Second, the Republicans are carrying the baggage of policies accumulated over three decades in which ordinary Americans have seen their living standards decline. This is hardly a golden age that Americans are anxious to return to.

Third, much of the GOP's conservative base was built on a backlash against the social progress of the 1960s. If anything, the election of a Black president, and the growing public support for the rights of LGBT people, among other points, has shown that the social underpinnings of this sort of backlash politics have eroded.

There is one final factor that would certainly derail the conservatives' hopes for a comeback. And that is the possibility of a revived labor and working-class movement from below.

In an interview published in the March/April issue of International Socialist Review, socialist labor scholar Kim Moody suggests that economic inequality and the political rejection of the neoconservative agenda may produce "the next upsurge [of the labor movement] we [i.e. labor activists] talk about a lot."

Moody lays particular stress on the potential for organizing in the traditionally anti-union, but economically vital, South. If labor manages to organize significantly in the South--currently, the geographic base of the Republican Party--it will strike a blow for labor. And It will also likely consign American conservatism's main political institution to the shelf for a long time.