The limits of liberalism

The history of American liberalism isn't of promoting radical change, but of governing the capitalist system in the interest of preserving the status quo.

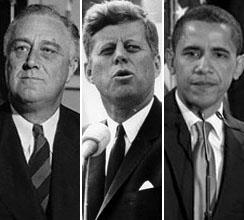

WHILE MOST people who would call themselves liberals have been quite pleased with President Obama's debut, a growing minority is becoming restless at what they see as the administration's too-easy capitulation to business forces.

A case in point was Obama's May 10 announcement, with much fanfare and press hoopla, of a pledge from 10 major health industry interest groups to cut the growth of health care spending over the course of the next decade. The $2 trillion in health spending saved could help the administration enact a comprehensive health care reform bill, administration officials noted.

But some liberals weren't so sure that this announcement was good news. It had the aspect of a behind-the-scenes deal in which the administration won an industry promise in exchange for making some unknown "compromise." Former Labor Secretary Robert Reich, writing in his blog at the Talking Points Memo Web site, noted:

The only troubling thing about the President's statements today concerning health care reform was what he did not say: that he wanted any health plan that emerges from Congress to include a public insurance option for Americans who do not want to buy private insurance. But without this option, there will be no pressure on private insurers to adopt all the other reforms to control costs or give all Americans access to affordable care.

Did Obama trade away the "public option" to win support from the health industry? We'll soon find out.

But this modus operandi is becoming a bit of a pattern. Already, the administration's policies to address the financial crisis--from the bank bailouts to the rigged "stress tests"--appear to have been designed to disrupt Wall Street's business as usual as little as possible. For this reason, liberal economists like Nobel Laureates Paul Krugman and Joseph Stiglitz have denounced the administration's policies as, at best, keeping "zombie banks" on life support--or, at worst, robbing taxpayers.

All of this dismays liberals who believe that they have a once-in-a-generation opportunity to enact overdue reforms. Instead, they see the administration compromising with big business that has interests in making whatever reforms are passed as toothless as possible.

For example, if the administration was truly interested in a health care system that would contain costs and cover every American, the simplest and most cost-effective solution would be to do what virtually every other industrialized country does: cover the population through a government-run "single payer" system.

Instead, the health care reform that is likely to emerge from this Congress will be a jerry-built compromise designed to provide enough incentives for health industry "stakeholders" (to use the parlance in vogue in Washington today) not to sabotage the plan. But this deal with the devil will make whatever reform is passed weaker and more inefficient as a result.

THE STANDARD arguments for explaining these capitulations to big business include everything from parliamentary excuses ("we've got to get 60 votes in the Senate") to the fact that Obama and congressional Democrats have pocketed millions in corporate cash. While these explanations tell part of the story, they avoid a bigger picture that places today's pressure toward reform in the context of American liberalism's history as one of the two main philosophies (along with conservatism) for governing American capitalism.

Despite what conservatives are shouting these days, liberalism is not a version of "socialism," or even social democracy. It's one way to run a capitalist economy in the interests of capital. We can see this even when we look at liberalism's "high tide"--the New Deal era of the 1930s and 1940s, under Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

The Democratic Party's brand of liberalism in that period was pretty mild stuff.

First, it refused to countenance large-scale government intervention into labor markets or the operation of the economy. Unlike European social democracy, American liberalism didn't support nationalization of industries or "cradle-to-grave" social welfare policies. Liberals accepted that the paramount aim of American economic policy was to maintain conditions for corporate-led economic growth.

Even in the New Deal's halcyon days, Democratic programs fell far short of working-class demands or welfare policies in other advanced capitalist countries. As historian Kevin Boyle noted, "In 1949, after four full terms of Democratic Party rule, the United States ranked last among industrial capitalist states in social welfare expenditures."

Second, liberals did not--and still do not--question the necessity of a massive military machine or the imperialist aims for which it is deployed. In fact, "Cold War liberalism" rested on expanding the Pentagon. By the 1960s and the presidency of John F. Kennedy, the liberal commitment to the war in Vietnam was helping to starve domestic "war on poverty" programs. Obama's growing commitment to a wider war in Afghanistan and Pakistan may have the same impact today.

Liberalism remained the postwar era's guiding economic and political ideology because it served the needs of an expanding capitalism. U.S. economic expansion depended on increased investment in technology (and in a technologically sophisticated workforce). Moreover, economic growth pulled larger numbers of workers on the margins of the U.S. labor market into paid labor.

Liberal government policies helped to facilitate these changes required by the postwar economy. Federal programs like the G.I. Bill of Rights and the National Defense Education Act of 1958 subsidized an expansion of higher education and the creation of a technologically equipped workforce. These programs were justified as part of the Cold War need to "keep up with the Russians"--which only added to their appeal.

Government programs such as Head Start, Medicare, Medicaid and child nutrition programs added to the working class' "social wage," underwriting the expansion of the postwar workforce. State expenditures on some roles formerly left to women in families--caring for the elderly, assuring adequate nutrition for kids--helped increase the numbers of women available to enter the paid labor force.

Liberals championed and won these reforms--all of which aided U.S. capitalism.

Today, Obama makes many of the same pitches for his policies: arguing, for instance, that health care reform will help U.S. business compete against firms from countries whose governments cover health care costs.

This may be true. But when the policies are crafted from the point of view of the interests of big business, they are just as likely to be curtailed or jettisoned if Corporate America feels it doesn't need them. That was big business' attitude through most of the previous political era, when free-market ideology ruled the day. Democrats, as much as Republicans, abetted the process of counter-reform.

As political scientist Thomas Ferguson once remarked, this factor explains why the Democratic Party

left ordinary Americans alternately confused, perplexed, alarmed or disgusted, as they tried to puzzle out why the party did so little to help unionize the South, protect the victims of McCarthyism, promote civil rights for Blacks, women or Hispanics, or in the late 1970s, combat America's great 'right turn' against the New Deal itself.

To such people, it always remained a mystery why the Democrats so often betrayed the ideals of the New Deal. Little did they realize that, in fact, the party was only living up to them.