The nightmare that doesn’t end

reports on the suicide of a Guantánamo detainee--and a rare protest of several who remain at the prison.

THE SUICIDE of Guantánamo Bay detainee Mohammad Ahmed Abdullah Saleh al Hanashi on June 1 offered a stark reminder that the Obama administration has yet to uphold its pledge to treat prisoners of the "war on terror" more humanely than its predecessors.

Hanashi, one of approximately 240 prisoners still at the camp, was found "unresponsive and not breathing," according to a Pentagon spokesperson. The government has refused so far to issue further details.

The Yemeni detainee, an alleged Taliban fighter, had been held at Guantánamo since February 2002. Although military officials refuse to confirm it, medical records show that Hanashi's weight dropped to just 87 pounds in December 2005--suggesting he may have participated in a long-running hunger strike carried out by some detainees.

David Remes, a lawyer who represents 16 other Yemeni prisoners at Guantánamo, told the New York Times that Hanashi had been one of seven prisoners kept under sedation in a psychiatric ward at the prison, and that he had been force-fed in a restraint chair.

Hanashi is the fifth detainee to commit suicide at the prison camp. In 2006, when three detainees took their own lives at the same time, the commander of Guantánamo at the time, Rear Adm. Harry B. Harris Jr., declared that the detainees "are smart, they are creative, they are committed. They have no regard for life, neither ours nor their own. I believe this was not an act of desperation, but an act of asymmetrical warfare waged against us."

Harris' lack of compassion was all the more repulsive considering that one of the detainees who killed himself had been just 17 years old when he was sent to Guantánamo.

Dozens of suicide attempts had reportedly taken place before the three detainees succeeded in 2006 (and, it's assumed, since then as well). Rather than express concern for the welfare of prisoners suffering the prospect of indefinite detention, however, U.S. officials refused to even count the number of suicide attempts, instead classifying them as instances of "manipulative, self-injurious behavior."

But as Shafiq Rasul, a British man released from Guantánamo, who went a hunger strike while in detention to protest beatings, told the Associated Press in 2006: "There is no hope in Guantánamo. The only thing that goes through your mind day after day is how to get justice or how to kill yourself. It is the despair--not the thought of martyrdom--that consumes you there."

According to the New York Center for Constitutional Rights, Hanashi was one of about eight detainees currently in the camp who had never consulted with an attorney. A law firm had recently accepted his case, but had not yet met with him. It was unclear whether Hanashi would have accepted a meeting.

Hanashi's suicide raises serious questions about conditions for detainees under the new Obama administration.

Despite Barack Obama's promise to close the camp by January 2010, Congress recently voted to reject funding for the closure of the camp. But as Shayana Kadidal, a lawyer at the Center for Constitutional Rights (CCR), told the New York Times, "Every day that passes makes it more likely that people will die in detention on President Obama's watch."

"The cost of keeping Guantánamo open could not be clearer at a time like this, both for the men there and for the perception of the U.S. in the world," the CCR said in a statement.

THAT COST was on display when a handful of journalists attended a hearing at Guantánamo for detainee Omar Khad, a Canadian citizen.

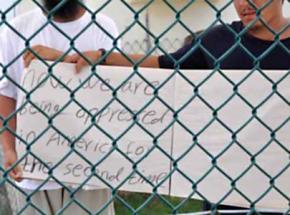

Following the hearing for Khad (and just hours before Hanashi's suicide), the journalists were witness to a rare moment at the camp, as two detainees managed to hold a small protest--holding up signs for reporters written in crayon.

"We are the Uighurs," said one sign. "We are being oppressed in prison though we had been announced innocent." Another read, "We were an oppressed nation in China. Now we are being oppressed in America for a second time." A third said, "We are being held in prison but we have been announced innocent acorrding (sic) to the virdict in caurt. We need to freedom."

The men are part of a group of 17 Uighurs--ethnic Chinese Muslims from the Chinese region of Xinjiang (called Turkestan by the Uighurs themselves)--currently held at the camp.

The Uighurs are, by all accounts, innocent of any terrorist activities against the U.S. They were traders, taking Chinese leather to Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan and Afghanistan. In the Afghan city of Jalalabad, when the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan began, the men seem to have been "sold" to U.S. forces by tribesmen enticed by the prospect of a large reward.

While at Guantánamo, the Uighurs have been subject to the same abuses we now know were common at the prison camp. At one point, Chinese officials were allowed to interrogate Uighur prisoners--China claims they are anti-government separatists.

According to a 2008 Justice Department inspector general's report, the U.S. used sleep deprivation and other harsh interrogation tactics to "soften up" the detainees for Chinese interrogators. The report stated:

While the Uighurs were detained at Camp X-Ray, some Chinese officials visited GTMO and were granted access to these detainees for interrogation purposes. The agent stated that he understood that the treatment of the Uighur detainees was either carried out by the Chinese interrogators or was carried out by U.S. military personnel at the behest of the Chinese interrogators. He said he also heard from the Uighur translator that other Uighur detainees experienced this same treatment.

U.S. courts have ordered the men released on more than one occasion. Last year, U.S. District Judge Ricardo Urbina ruled that, because the government provided no proof the men were enemy combatants or security risks, they should be released to live with Uighur families in the Washington area until a more permanent situation can be found.

Yet the men remain imprisoned, in part because the government says it does not know where to send them--despite the fact that an earlier group of Uighurs imprisoned at Guantánamo was given asylum in Albania.

Chinese authorities are demanding that they be sent back to face what would likely be show trials on charges of separatist activities. Any other country that gives the Uighurs asylum risks retailiation by China.

"Nobody is going to want to take the Uighurs because of the Chinese pressure," attorney Sabin Willitt, who represents one of the Uighurs, told the Los Angeles Times in February. "Every time we got an audience with the third deputy assistant minister of [any country], we always found the Chinese minister was ahead of us, having had a full lunch with the foreign minister."

THOUGH AT least one federal court had ordered the men released on U.S. soil, both Democrats and Republicans have denounced the idea that any Guantánamo detainees might be eventually released on U.S. soil (even if they are innocent).

Instead of releasing the Uighurs, the Obama administration is instead attempting to spin their continued incarceration as not really "that bad."

Incredibly, even as the two Uighur detainees protested in front of reporters, a Navy officer told the press that this showed how good their treatment is. "As you can see, they are pretty much free men," said the Navy chief who supervises sailors guarding the men at the half-acre compound. He called the protest "their own doing."

Held at Camp Iguana, the lowest-security part of the camp, the Uighurs are reportedly given special privileges, including access to a computer lab.

But it's absurd to claim they are "pretty much free men." They are living thousands of miles away from their homes and family, under armed guard and constant surveillance. They still have been imprisoned for more than seven years with no trials.

They are still, at bottom, prisoners of war--as one prisoner reminded reporters who watched the impromptu protest.

"Obama didn't release us," he told them. "Why?"