Setting an example of resistance

reports on the struggles of Fort Hood soldiers who have stood up to resist the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

IN THE early morning of August 29, Victor Agosto, a soldier who refused to deploy to Afghanistan, walked out of the Bell County Jail a few days short of his 30-day sentence. A white van dropped him deep within the bowels of Fort Hood, Texas, the largest military base on earth.

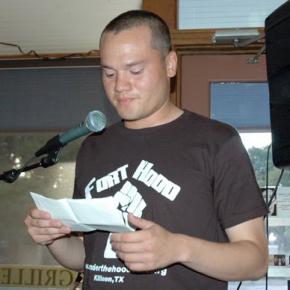

On an unusually pleasant 95-degree afternoon at Under the Hood Café, the G.I. café just outside Fort Hood, there was a celebration for a hero, a barbecue and fundraiser, and a rally to continue the fight for the other men, women and families victimized by the war machine and inspired by Victor's courage.

While serving a non-combat tour in Iraq, Agosto came to realize that the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan served only U.S. imperialism, and that the immense human suffering caused by these misadventures couldn't be justified. Last May, he stayed within the Fort Hood barracks and refused to go with his unit to Afghanistan.

About 50 activists, military and ex-military members, and their families from around the state gathered at The Hood where Agosto had announced his decision.

Agosto's support from an activist campaign from the beginning and the resulting publicity surrounding his intent to "put the war on trial" got him out with a reasonable sentence--a 30-day jail sentence, reduction of pay and less than honorable discharge.

Support rallies and marches began on day one, continued inside and outside the base during his trial and followed him outside the jail where he served his sentence. When Agosto arrived at the county jail, the inmates recognized him from watching the trial results and protests on television.

Agosto reported that his reception from his fellow inmates was overwhelmingly positive. Any day, Agosto will be permanently released from the weighty shackles that bind him to the military.

The featured speaker for the celebration was ex-colonel and peace activist, Ann Wright, who resigned from her diplomatic post in 2003 in protest of the decision to go to war in Iraq. After celebrating Agosto's release, Wright urged the crowd to keep up the fight against U.S. wars and in support of resisting soldiers.

Agosto seemed overwhelmed by the enthusiasm of his supporters. "I had no idea four years ago I would be standing here like this," he said. "I knew I would get support, but...nothing like this."

Then attention was turned to other soldiers needing support. "Very few people," said Wright, "will have the courage to go to jail for their conscience."

ANOTHER FORT Hood soldier, Travis Bishop, inspired by Agosto, refused to deploy to Afghanistan shortly after Agosto's courageous stand.

Bishop began to question his military service during a tour in Iraq. "I started to see a big difference between our reality there and what was in the news," he told journalist Dahr Jamail in an interview for the Truthout Web site. A Christian, he then began to study the tenets of his faith, and realized that he was opposed to war on religious and moral grounds.

Only three days before he was to deploy, Bishop learned at Under the Hood that it was possible to apply for conscientious objector (CO) status. On the day his unit deployed, Bishop went AWOL for a week to prepare his application for CO status, then returned and turned himself in.

While his CO application was being considered, he was charged with missing a movement and disobeying a direct order. Bishop pled not guilty on all counts at a special court-martial on August 15.

Bishop's lawyer, James Branum, who also represented Agosto, based his defense on Bishop's not having been trained or informed of his rights as a conscientious objector. Bishop's commander, Capt. Christopher Hall, admitted to the court that he had not provided CO training to Bishop's unit.

The judge, Major Matthew McDonald, said that such training was irrelevant to Bishop's case. "If every soldier in the Army who disobeyed an order could claim it was because they weren't notified of conscientious objector status, we probably wouldn't have a military anymore," he concluded. Indeed!

The jury of officers several ranks higher than Sgt. Bishop had no problem going along with this twisted logic. One of the jurors had to be woken up during the trial. Another, a Lt. Col. Atkins, rolled his eyes and shook his head throughout most of the defense.

To counter character witnesses attesting to Bishop's sincerity, the prosecution called Lt. Col. Ron Leininger, the chaplain who recommended that Bishop's CO status be denied. Bishop told Truthout that Leininger lied and misrepresented facts in describing Bishop's interview for CO status. "The chaplain only spoke with me for 20 minutes, took two calls on his cell phone and was texting the whole time," he said.

Leininger's written report on his meeting with Bishop had several mistakes, including calling Bishop by the wrong name.

Bishop was found guilty of all charges. He was sentenced to one year in prison, a rank reduction to private, forfeiture of two-thirds of his pay for one year, and a bad-conduct discharge.

Branum plans to appeal Bishop's case and continue the fight for mandatory training on the right to apply for CO status through a series of military courts and beyond--as far as the U.S. Supreme Court if necessary. He compares the right to this training to the Miranda decision, which requires that the accused be advised of their rights. "It's not a right if you don't know it exists."

"Someday," Branum hopes, "soldiers will be read their 'Bishop rights.'"

The huge swell of support that developed instantly when Agosto refused to deploy did not begin in the same way for Bishop. This was because Bishop was so new to the process and still learning the ropes, Branum explained. He added that Bishop wanted his religious views known, and didn't want them diluted in combining the movements.

Whether this had something to do with his receiving a much harsher sentence than Agosto, or whether the Army felt it couldn't afford to let another one get off so easy is unclear. But as Bishop entered the courtroom and as he left in shackles, he was surrounded by an enthusiastic group of activists dedicated to war resistance, for whom he is now a standard-bearer.

Outside the courtroom after his sentencing, Bishop thanked his supporters. "It means a lot to me you are here in my support," he said. "This is not the end, by any means. This is the beginning. When I get out, I'm going to be louder, more active and pissed off."

In his prison blog dated August 20, Bishop explained the mission: "Though I suffer a harsh personal loss, the gain for this movement is incredible. Already, I have heard of others who have been influenced by mine and Victor's decisions and actions, and it warms my heart. Ultimately, the goal is to end these wars...My hope is that others learn from mine and Victor's sacrifices. They are small when compared to the ultimate gain.

"TRAVIS HAS been a busy little beaver in the Bell County Jail, organizing study groups in his cell and talking about issues important to military prisoners," Branum told the crowd gathered at Under the Hood. It was here that Bishop met Leo Church and heard his story of military abuse and indifference.

Bishop hooked up Church with his lawyer Branum, who told Church's story: Shortly after he finished basic training, Church received a call that his wife and two young daughters were homeless and living in a van in Arlington, Texas. His company commander denied him permission to leave to pick up his family. He went AWOL, picked up his daughters and returned to the base, where, for the crime of putting his family first, he was given an Article 15 (a non-judicial military punishment), and his pay was cut in half.

There was no housing or child care provided for his children on post, and he was told to bring them with him to work--clearly not a safe situation. He went AWOL and took his daughters to Amarillo, where he stayed with them and his mother. When the Army picked him up in 2007, his wife came and took his daughters, saying he couldn't see them again until he left the Army.

While absent from the Army, Church had rebuilt his life--a good job, new marriage and the birth of a son. Now serving eight months in prison and a bad conduct discharge, his wife is struggling to survive, and their son is up for adoption.

Branum is appealing Church's charges, hoping for a shorter sentence and a reinstatement of his salary.

Both Bishop and Church have left the Bell County, Texas jail for a military prison at Fort Lewis, Wash.

There is much that the activist community can do to support these two men and help with their legal appeals. Amnesty International has initiated a letter-writing campaign for Bishop, and Church's wife has created an online petition. Money is needed for legal fees. Both appreciate letters letting them know that their support continues and that the stands they have taken will help their fellow soldiers.

In his blog from behind bars, Bishop admits that he is terrified of his year in prison, but says "it would be scarier still to know that my fellow soldiers who feel as we feel would never find out what we are trying to accomplish had I not gone to prison...Victor and myself are starting something big...and it is now up to all of you to continue on."

Meanwhile, back at Fort Hood, the spirit of resistance is growing at Under the Hood. Fort Hood soldiers have created a documented, truth-telling underground newspaper, The Not So Great Place, which exposes the biggest military base in the world for what it is. Its mission statement: We are 100 percent pro-soldier, but 100 percent anti-military.

It's important that Under the Hood continues to give soldiers and veterans hope and knowledge of their rights--and to be a thorn in the side of the military.