“Bolshevik and proud of it”

Eugene Debs was, as he later wrote, "baptized in socialism in the roar of conflict" as a leader of the American Railway Union strike against Pullman Co. in 1894. Following his release for his part in the strike, Debs dedicated the last three decades of his life to the cause of socialism. looks at Debs' mighty contributions to the movement.

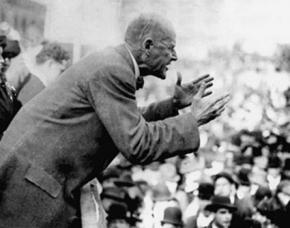

NO OTHER figure in the American socialist movement became so widely known as Eugene Debs. Moreover, no other figure did so much to bring the message of class struggle and the need for a socialist transformation of society to a mass audience as he did.

His articles appeared in dozens of radical newspapers and journals, like the Appeal to Reason, which circulated to nearly half a million readers. His agitation on behalf of workers' struggles and for class unity was ceaseless. Day after day, year after year, he appeared on public platforms in auditoriums and lecture halls throughout the country.

Debs' speeches hammered home several main themes: the vast gulf that separated the possessing class from the mass of workers; the servile relationship of all institutions of the capitalist state (especially the courts) to the capitalist class; the legitimacy of workers' struggles against exploitation and oppression; the need for workers' unity; the necessity of getting rid of capitalism and establishing a society ruled by the direct producers.

From the mid-1890s onward, Debs was instrumental in building the socialist movement. In 1901, he helped form the Socialist Party (SP), created from a merger of three smaller socialist organizations. But Debs so disliked the factional wrangles involved in the unification process that he distanced himself from internal political struggles in the SP thereafter.

Such an attitude reflected the loose structure of the SP. As the party's main spokesman, Debs continued to say and do as he pleased. At the same time, much of the party's leadership--people like Morris Hillquit and Victor Berger--stood to Debs' right.

Debs was never central to internal SP debates and organizational matters. On the contrary, his strength was in his role as a working-class agitator. His understanding of class politics came not from theoretical study and polemic, but from direct involvement in workers' struggles.

Throughout the first decade of the 1900s, Debs was responsible for establishing hundreds of SP branches. Wherever he spoke, he helped start new organizations and to reinvigorate old ones.

He also assisted workers in organizing locals of trade unions in towns where he spoke. As a persistent champion of industrial unionism, Debs used every opportunity to convince workers to move beyond the narrow craft approach that characterized the American Federation of Labor (AFL).

One of the most pressing tasks of the labor movement was to defend political prisoners jailed or condemned to death for their role in class struggle. Debs campaigned to defend William Haywood and Charles Moyers, prominent leaders of the Industrial Workers of the World who, in 1906, were framed for the murder of a former Idaho governor. A massive outcry from the labor movement in the U.S. and abroad eventually led to their acquittal.

Debs also defended other labor activists, like Tom Mooney and Warren Billings, trade unionists and socialists framed in a San Francisco bombing. Toward the end of his life, he assisted in the campaign for the executed anarchists Sacco and Vanzetti.

BETWEEN 1900 and 1920, Debs ran for president five times as the SP's candidate. In its first 12 years, the SP saw its electoral strength grow steadily. In 1908, Debs toured the country in a train called the "Red Special," speaking to tens of thousands at whistle-stop rallies. In the 1912 elections, Debs brought the SP to its highest point of electoral success, polling nearly a million votes.

While many SP leaders saw elected office as an end in itself, Debs used electoral activity as a platform for putting across the ideas of socialism.

When war broke out in Europe in 1914, Debs was unequivocal in placing the blame on the capitalist system. He characterized those socialists who supported the war as traitors to the working class. He campaigned against any involvement of the U.S. in the conflict.

The public barrage for war "preparedness" was difficult for many to resist. When President Woodrow Wilson brought the U.S. into the war in April 1917, many of the SP's prominent intellectuals and writers defected to the pro-war camp.

Despite the vicious repression that government courts and vigilante bands mounted against them, antiwar socialists like Debs stuck to their convictions. In a series of show trials, the federal government convicted and imprisoned dozens of SP leaders, like Kate Richards O'Hare, Charles Ruthenberg, Alfred Wagenknecht and others for publicly opposing the war.

Debs understood that before long, the government would seek some pretext to imprison him as well. The occasion came with a speech that Debs delivered in June 1918 to the state SP convention in Canton, Ohio. This speech, celebrated as one of Debs' finest, in fact did not differ greatly from scores of similar addresses he made during the war.

The Canton speech was an indictment of the capitalists' war and of those socialists who supported "their" governments:

They lack the fiber to endure the revolutionary test; they fall away; they disappear as if they had never been. On the other hand, they who are animated by the unconquerable spirit of the social revolution; they who have the moral courage to stand erect and assert their convictions; stand by them; fight for them; go to jail or hell for them, if need be.

They are writing their names, in this crucial hour. They are writing their names in fadeless letters in the history of mankind.

Debs condemned the role of patriotism in maintaining oppression:

In passing, I suggest that we stop a moment to think about the term "landlord." Landlord! Lord of the land! The lord of the land is indeed a superpatriot. This lord who practically owns the earth tells you that we are fighting this war to make the world safe for democracy. He, who shuts out all humanity from his private domain; he, who profiteers at the expense of the people who have been slain and mutilated by multiplied thousands, under pretense of being the great American patriot.

It is he, this identical patriot, who is fast the arch-enemy of the people; it is he that you need to wipe from power. It is he who is a far greater menace to your liberty and your well-being than the Prussian Junkers on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean.

The Justice Department had stenographers record the speech, and two weeks afterward, a federal court in Cleveland indicted Debs for violating the Espionage Act.

During his trial, Debs did not dispute any of the facts of the case. He told the jury he "would not retract a word...I have been accused of having obstructed the war. I admit it. Gentlemen, I abhor war."

Debs' conviction was a foregone conclusion. At age 64, he was sentenced to 10 years' imprisonment in the Atlanta federal penitentiary. Prison conditions were so disagreeable that Debs' already frail health broke down completely. Prison officials, concerned that so famous a political prisoner not die in their charge, improved conditions for Debs. Under better care, he recovered.

BUT DEBS was much troubled by the discord in the socialist movement he had so long been a part of. During the war, and especially after the 1917 Russian Revolution, the left wing of the party had grown in numbers and influence. By September 1919, a series of splits had produced three separate organizations: the Communist Party (CP), the Communist Labor Party (CLP) and the remnants of the SP.

In prison, Debs was out of touch with the issues and developments in the party. More crucially, he was deprived of any contact with working-class militants. On most issues--advocacy of industrial unionism, support for the Bolsheviks, the necessity of revolution in the U.S.--his sympathies lay with the position of the CP and the CLP rather than the reformist leaders of the SP.

But his overwhelming desire was for socialist unity. "I do not believe that there is any real difference among the rank-and-file of socialists. The real contentions very likely lie in the leaderships of the different groups. The socialists movement must rise to the occasion this year and united the industrial and political wings," he wrote.

In 1920, an anti-radical hysteria exceeding even that of the war years was in full swing. The SP again nominated Debs as its candidate for president to run from prison.

Debs accepted, but he was critical of the SP's platform, which "could have been more effective if it had stressed the class struggle more prominently and if more emphasis had been placed on industrial organization...We are in politics not to get votes, but to develop the power to emancipate the working class."

Debs also criticized the SP leaders' attack on the CP and their denunciation of the "dictatorship of the proletariat" under the Bolsheviks. Debs was unequivocal: "During the transition period, the revolution must protect itself...I heartily support the Russian Revolution without reservation."

In the elections, Debs polled slightly more votes than he did in 1912--nearly 1 million. These votes for "Prisoner 9653" represented a protest against government repression at least as much as an endorsement of socialist politics.

Nevertheless, the SP continued to decline in strength. Neither the CP nor the CLP supported Debs' presidential candidacy. Both groups were pursuing a sectarian ultra-left course utterly dismissive of the tactical value of elections under capitalism.

The CP was quite unable to see the need for promoting the unity of the working class in action against the attacks by the capitalists, and for winning over workers still looking to reformist leaders in the SP.

Thus, in the labor movement's mounting campaign for amnesty for all imprisoned opponents of the war, the CP was completely absent. Such sectarian behavior made Debs resentful of the Communists, and he kept his distance from them even after the CP and CLP merged to form the Workers Party in 1921.

Debs was released from prison on Christmas Day 1921 after his sentence was commuted by President William G. Harding. The bad state of his health would no longer permit anything like the grueling schedules he had endured before his imprisonment.

Both Communists and Socialists were pressuring Debs to declare publicly for one group or the other. Debs had serious disagreements with both and tried to straddle a middle position. He was officially a member of the SP and even became national chairman of the party in 1923. But many of his positions were closer to those of the CP.

The scope of his political activities narrowed as his failing health took him into and out of sanitariums to convalesce. Eugene Debs died in October 1926, convinced to the last that the socialist revolution, while it might be delayed, would inevitably arise.

This article originally appeared in Socialist Worker in December 1989.