Bob Marley’s legacy of unity

Thirty years after his death, looks at the legacy of a reggae legend.

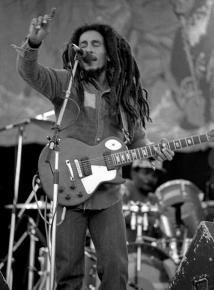

THIRTY YEARS after his death, Bob Marley's shadow looms larger than ever. There can be no doubt that he long ago entered the pop legend pantheon next to such names as Lennon, Joplin, Morrison, Strummer, and Cobain.

To many, Marley's music is synonymous with reggae itself. Legend, his posthumous "best-of" collection, has to date sold over 25 million copies, making it the best-selling reggae album in history. He's been the subject of close to two dozen books (the most recent of which was released only a few months ago). His image and sounds are used to sell everything from incense burners to Jamaican vacation packages.

And yet, as is so often the case with dead rock stars, there is something of a disconnect. One wonders what the militant anti-racist would think of the privileged white frat-boys who smear themselves with blackface as an "homage" to Marley at campus Halloween parties. Similarly, it's hard to look at lavish Jamaican resorts existing next to such grinding poverty and wonder if the musician's calls of "one love" now ring hollow.

Luckily, Marley's roots run a lot deeper. A website dedicated to his memory rightfully states that "in the Third World his impact goes much further. Not just among Jamaicans, but also the Hopi Indians of New Mexico and the Maoris of New Zealand, in Indonesia and India, and especially in those parts of West Africa from which slaves were plucked and taken to the New World, Bob is seen as a redeemer figure".

These are not exactly the suburban kids that the marketers of the Western music industry attempt to target. At the time of his death, Bob Marley was one of the first international superstars to emerge from the developing world. Such credibility cannot be so easily sanitized. With revolt now shaking North Africa and the Middle East, it seems that the "suffering masses" who Marley tried to reach were indeed listening. Ultimately, it makes his legacy that much more potent and inspiring.

Heavy manners world-wide

MUCH AS some condescending historians would like to paint Jamaica as a land of the exotic-yet-savage "other," the fact is that it's impossible to read descriptions of Kingston in the middle 20th century without being reminded of countless places around the world. (Indeed, as the economy remains sluggish, more than a few places in the U.S. seem to fit the bill too). The scenes that Marley would so deftly relate in songs like "No Woman, No Cry" and "Concrete Jungle" were a simple and inescapable fact of life: massive and under-funded government housing blocks, shantytown slums, poverty and degradation.

This was Jamaica under the British Empire. It bears repeating that Jamaica was (and is) an island profoundly rich in resources. But centuries of colonialism meant that scant few of those riches were ever seen by most Jamaicans. It was impossible to separate the grinding poverty of the nation's Black majority without recognizing it as a result of white Western dominance.

Marley, of course, made this recognition--a fact that no doubt weighed on him with the knowledge that his father was a white British naval officer. In an interview some years later he had this to say about that legacy:

You learn in school about Christopher Columbus, Marco Polo. What about the traditions of African people? We want to learn that in school! We don't want to learn about Christopher Columbus and all of that...all it lead you to do is be a criminal. When you study how these people went to Jamaica, see the Arawak Indians, kill them off. And then they say that the discovered the land! That is just pure rape and murder and piracy.

When Bob Marley recorded his very first single in 1961, Jamaica was still under British rule; the following year would bring independence, but the West's economic dominance would continue. Given this, it's not hard to understand why the early Rastafari movement and others like them would gravitate toward Black nationalists and Afrocentrists like Marcus Garvey (himself originally from Jamaica).

Marley wouldn't convert to Rastafari until 1969, but his concern for unity was clear even in his early tracks. "Simmer Down", probably the best known of these, calling on the ghetto Rude Boy gangs to bring an end to the violence. Recorded in 1963, it was Marley's first hit, and by February of '64 was Jamaica's number one song.

"Simmer Down" is clearly not the kind of song that springs to mind when one thinks of Bob Marley; it's much more of a traditional ska song, a la Desmond Dekker. But listening to it, reggae's roots are clear. The influence it takes from soul and R&B are apparent, but the song drips with the essence of "heavy manners." Its joyous, youthful swagger is tempered by a sense of inevitable hard days approaching.

Even before ska, rocksteady or reggae began to take shape, their roots ran deep. Over the previous two decades Jamaica had developed a rich, fiercely competitive music scene. Radios could pick up stations from nearby Miami or New Orleans, exposing listeners to everything from jazz and boogie-woogie to Motown and doo-wop. As working-class Jamaican men were often forced to look abroad for work, the nation's burgeoning sound-system scene took advantage of it.

Lloyd Bradley describes the process in his landmark book Bass Culture: When Reggae Was King:

Only the very biggest operators could afford to travel to the USA to shop for records, so the majority of sound-system music arrived courtesy of merchant seaman and returning migrant workers looking to supplement their income...A proportion of that informal import trade would be pre-arranged, with the secondary level of sound men having made deals with seamen whose judgment they respected, asking them to shop for certain types of record by certain artists or producers, occasionally allowing the voyager to surprise them. But the majority of business was with the little sound men and strictly freelance, resulting in spirited bartering or "higgling," being carried out on the quayside between entrepreneurial rivals and their prospective clients.

MARLEY WAS one of these countless Jamaicans who traveled to the U.S. to find work. In 1966 he joined his mother in Delaware, where he worked in a Chrysler plant. When he returned to Jamaica a year later, he brought something more than just records with him. In the United States, the civil rights movement had found its way from the South into the ghettos of the North, where it was quickly transforming into the demand for Black Power. Demonstrations against the Vietnam war were becoming commonplace. Both were to have a profound impact on the young Bob.

By the end of the decade, other liberation movements in the developing world had turned the tide against their former colonizers. For the first time, the people of the "Third World" seemed to speak with one voice against their Euro-American exploiters. It wasn't just Vietnam; it was Angola, it was Cuba, it was South Africa and Jamaica and Brazil. What's more, ordinary workers and students in the West--be they Black, white or Latino--seemed ready to listen.

It was in this context that Marley became the "first international Third World superstar." Others--Fela Kuti, Victor Jara--would gain world-wide acclaim, but often not outside their regions of origin until their deaths. As such, Marley's songs took on a feel of profound, bottom-up internationalism even as his sound became almost synonymous with Jamaica itself. "Get Up, Stand Up", "Burnin' and Lootin'", "Uprising", "Revolution", all were starkly related to his own experiences in Jamaica, and yet could fit any number of places around the world.

When asked to play the One Love Peace Concert in 1978, Jamaica was skating on the edge of a civil war. The nominally socialist government of Michael Manley had over the past six years instituted a minimum wage and free higher education. He had also sought ties with Cuba, which sent the CIA into panic mode. By the time of the concert, the U.S. had covertly handed over unknown amounts of money and guns to Manley's rival, conservative Edward Seaga. Armed gangs on both sides had turned the country to a powder-keg.

Marley famously performed a headlining set at this concert only two days after he, his wife Rita, and his manager were shot by unknown assailants. Just as well-known is the fact that he later brought both Seaga and Manley onstage to shake hands.

But Marley, it would appear, wasn't merely stumping unity for its own sake. The One Love Peace Concert was also where he debuted the song "War." Taken from a speech delivered by Ethiopian King Haile Selassie in front of the United Nations, its sentiment certainly transcends whatever contradictions Selassie, or the Rastas who literally worshiped him, might have had:

Until the philosophy which hold one race

Superior and another inferior

Is finally and permanently discredited and abandoned

Everywhere is war, me say warThat until there are no longer first class

And second class citizens of any nation

Until the color of a man's skin

Is of no more significance than the color of his eyes

Me say war...And until the ignoble and unhappy regimes

that hold our brothers in Angola, in Mozambique,

South Africa, in sub-human bondage

Have been toppled, utterly destroyed

Well, everywhere is war, me say war

This strident internationalism, the invocations of a world-wide struggle, are two of Marley's contributions that continue to resonate through music. It wasn't too long until reggae--itself the result of intercontinental mix-mash--was transported back into America's ghettos and morphed yet again into an entirely new style.

In 1967, Clive Campbell, a 12-year-old Jamaican immigrant arrived with his mother to settle in the Bronx. Campbell's father, Keith, wasn't just an avid record collector (including reggae), but was known to have the loudest sound-system on the block. By 1973, young Clive was rigging that sound-system to play what would become legendary house and block parties. It wasn't long until Clive was better known as Kool Herc, and the beats he spun would prove to be crucial in the formation of hip-hop.

None but ourselves...

TODAY THERE is no shortage of figures and "fans" who would love to paper over this legacy. Militant anti-racism and anti-imperialism aren't exactly palatable to commercialization and respectability. A few years ago, for example, Jenna Bush--Dubya's daughter--told Oprah Winfrey that "my mom's a secret Rastafarian. She plays Bob Marley around the house!" Interesting assertion coming from the daughter of a man who refused to shake the hands of Haitian earthquake victims!

According to legendary music critic Robert Christgau, this watering-down of Marley's work is intentional. It's also shunned by a great many of his fans worldwide:

Most of the 14 million Americans who've bought the calculatedly anodyne Legend are in it for the herb. But Marley is very different for people of color such as the Tanzanian street vendors of Dar es Salam's [sic] Maskani district, one of many third-world subcultures to integrate his songs and image into a counterculture of resistance.

This counterculture can be felt across the African continent and beyond. Last year, the legendary Nas teamed up with Marley's son Stephen (known to the world as "Jr. Gong") to record Distant Relatives, a stunning piece of rap-reggae whose lyrical themes of anti-colonial empowerment could have come from the senior Marley himself.

The year before, Somali rapper K'Naan dropped The Messengers, a three-part online mixtape paying tribute to Bob Dylan, Fela Kuti, and, of course, Marley.

"Bob Marley had so much that he knew he had to give to the world," says K'Naan on the intro track.

He said "when it rains, it don't rain on one man's house." This is the words [sic] of someone who understands the impact that unity and division have on the world. He understood that; I think he was propelled by it. So he made music for us. "Little children learn your culture or you won't get no supper." These are the words that, I felt like, coming up, growing up...he was talking to me. And because of that, I'm looking at my culture.

The themes tying Nas, K'Naan and Jr. Gong together--unity, cultural pride, resistance to oppression--all seem to cull a deep and burning sense among the developing world. Plainly put, it's a longing for freedom. In Marley's time it seemed to be burgeoning reality, but since his death appears to have receded back into mere dreams. That is, until recently.

It started in Tunisia. Then it spread to Algeria and Morocco, then across North Africa: ordinary people rising up against dictators and repressive regimes. Corrupt, enriched on the backs of their people, it seems of little surprise that many of these governments have long been propped up by the West.

Egypt's case has by far been the most stunning. A country that only weeks before had played host to deadly attacks on the Coptic population now saw Muslim and Christian march arm-in-arm against the long-time "friend" of the U.S., Hosni Mubarak. In 18 days he was gone, and the West got a whole new image of the Muslim world--politically, culturally, and yes, even musically.

One of the many tracks to emerge from these uprisings and shoot round the Internet was "Rebel," written and recorded by one of Egypt's first hip-hop groups, Arabian Knightz. Released the night before Cairo's first "Day of Rage," it revolves heavily around a sample of Lauryn Hill--who, perhaps not coincidentally, has been long married to Bob Marley's son Rohan.

Though the protests have most notably spread across the Arab world into the Middle East, they are also finding their way down the African continent: rebellions against high food prices in Burkina Faso, Nigerian riots in the wake of an election many see as rigged, marches for better employment in Uganda, and public sector strikes that have brought Botswana to near-standstill. Though each of these are inspired most directly by their own domestic outrage, there can be little doubt that they've had the door opened for them by their neighbors to the north.

One Sub-Saharan artist who understands the meaning of all this is Thomas Mapfumo. Known as "the Lion of Zimbabwe," Mapfumo is a pioneer of the music known as chimurenga--which literally translates to "the struggle." When Zimbabwe was still known as Rhodesia, Mapfumo was a major figure in the fight against white British minority rule. Like Bob Marley, his songs have blended the sound of Western pop with the traditional music of his own country. In fact the two even toured together in the late '70s, and Marley paid specific tribute to the Zimbabwean struggle on his 1979 album Survival.

Rhodesian apartheid fell in 1980. Later in the decade, however, Mapfumo's songs began to turn their attention toward the poverty, corruption and brutality of President Robert Mugabe's regime. Mapfumo's songs were banned from radio, and in the early '90s he fled into exile in Portland, Oregon. Still recording music, he maintains that "the struggle is not over". In a recent interview with WBUR Boston's Tom Ashbrook, he put forth a belief that should be familiar to any Marley fan:

If you look at the whole situation, it's like, well, people have to unite again and actually do away with this evil system...African people should be united to work for the prosperity of Africa. They actually should come together and work as a nation. We are all Africans. Why don't we come together and come with a united Africa?

Mugabe clearly feels threatened by the revolts to the north. In early March, the president's police force arrested 49 socialists and trade-union activists for the "crime" of watching videos of the Tunisian and Egyptian revolutions. Though all were later released, six still face charges of treason; if found guilty, they face the death penalty.

Though Zimbabwe has yet to see the kind of rebellions that have rocked the Maghreb, the nation of Swaziland has come close. One of the world's last remaining absolute monarchies, poverty, disease and an almost complete lack of civil liberties has recently sprung the country's labor movement into action.

In mid-April, city streets were swamped by thousands of protestors. Though arrests and repression have caused union leaders to call off future rallies for now, groups like the Swaziland Solidarity Network (SSN) continue to organize. Denied basic resources that American or European organizers take for granted--resources like websites--the SSN's online presence is largely limited to Facebook and Google Groups.

In this small nation, where average life-expectancy doesn't exceed 32 years and any kind of dissent is viciously crushed, there are nonetheless vibrant hip-hop and reggae scenes. Reggae is particularly popular here; Swaziland once hosted one of the African continent's only reggae festivals. In the days leading up to the April protests, a member of the SSN posted lyrics from Bob Marley's "Redemption Song" on the group's forum.

It seems an odd choice: certainly one of Marley's best-known songs, but also by far his most intimate, written not long after being diagnosed with cancer. Themes of freedom and oppression are there throughout, but all seem to be tied back into the apparently personal notion of redemption. Modern interpretations of the song cast the singer as more spiritual than political, the "redeemer figure" brought up on his website. Why would this, out of all Marley's songs, be the one that inspires Swazi men and women to take up the mantle of insurrection?

Activist and journalist Nicole Colson provides insight into this:

This song moves from an isolated first-person in bondage, "old pirates, yes they rob I," to the movement of a collective. "We forward in this generation," and not just forward, but forward triumphantly...When I think of the word redemption, I tend to think of the definition to make something whole or win it back. I think he's literally talking about music that can make you a whole person, to help you step out of what you think are your limits--both in a personal and a political sense. But he also means, literally "liberation."

Indeed, there is something tragic in the wide relevance of Marley's music 30 years later. Namely, if so many around the world can identify with it, then the pain and oppression he spoke on hasn't gone anywhere.

But Marley was never one to buy into cynicism. Primarily, it seems to be the hope that people cling to in his songs. If so many in the most exploited, balkanized peoples of the world can look to his words as a call to action, then it shows that hope to be more than a pipe dream. It's during moments like these that music becomes more than mere sounds, and the true legacy of Bob Marley comes to life.

First published at PopMatters.com.