The crisis that won’t end

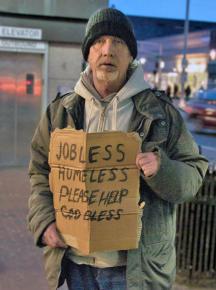

Is the world economy turning a corner--or teetering on the edge of the abyss created by the European financial crisis? There are plenty of economists making the case for each scenario. But even in the most optimistic forecasts, the outlook for working people in the U.S. and most of the rest of the world foresees high unemployment, wage stagnation and increased suffering caused by cuts in social spending--conditions that have given rise to a global revolt.

answers questions about conflicting signals from the U.S. and world economy.

THE MEDIA has been featuring stories about the improvements in the U.S. economy. Are the aftereffects of the recession finally fading?

THE GLASS-half-full crowd is pointing to a pickup in overall U.S. economic output, or Gross Domestic Product (GDP). While GDP grew at a miserable 1.8 percent for last year, it perked up to a 2.8 percent annual rate in the last quarter of 2011. That growth powered the creation of 200,000 jobs--a big jump after weak monthly job gains for most of the time since the recession officially ended in June 2009.

A prominent feature of the jobs growth is the creation of more than 136,000 manufacturing jobs last year. Overall, unemployment dropped to 8.5 percent, down from 9 percent in September.

After such relentlessly grim economic news, this uptick is noteworthy. But a closer look at the numbers only highlights just how far there is to go before unemployment levels recover to anything like pre-recession levels.

For example, if the same proportion of people were in the labor market as in 2010, the jobless rate today would be the same as it was at its high point in 2010, as Doug Henwood has noted. And the growth in manufacturing employment, while significant, is still a fraction of the more than 2 million manufacturing jobs lost in the recession and beyond. According to the Economic Policy Institute, the U.S. needs 10 million more jobs just to get to pre-recession levels.

Then there's the question of wages--which remain stagnant or falling as the result of wage freezes or pay cuts imposed by employers. That's why the recent bump in consumer spending that helped fuel U.S. economic growth was unsustainable. And since working people are still weighed down by debt from home mortgages, credit cards and the like, the banks aren't about to lend to support consumer spending. So demand will likely remain weak, limiting overall growth.

BUT IF the U.S. economy remains so lousy, why have corporate profits surged to record levels?

THERE ARE two key reasons. First, the biggest U.S. corporations get about 40 percent of their profits from overseas. So they're less dependent on the U.S. market than they were in the past.

A second factor is that Corporate America's class war has succeeded in wresting a record share of national income away from workers and into profits.

According to a study by Northeastern University researchers, between the second quarter of 2009 and the fourth quarter of 2010, corporate profits accounted for $464 billion of the $528 billion increase in national income over that period, with wages and salaries totaling just $7 billion. The researchers wrote: "The absence of any positive share of national income growth due to wages and salaries received by American workers during the current economic recovery is historically unprecedented."

The result of all this is that U.S. corporations are sitting on $1 trillion in cash. But they won't invest much of it in the U.S.--partly because they were spooked by the financial crash of 2008, which dried up credit for some time.

More importantly, big business is doubtful that such investments will be profitable. That's because the underlying reasons for the global recession of 2007-09--a glut of products and the factories that produce them--remains unresolved. If there's overproduction in a given industry, investment in that sector will pull back.

This low level of investment and weak demand has weighed down the economic expansion. As liberal economist Paul Krugman argues, we are in a depression--a prolonged period of economic weakness that persists even in an economic expansion.

WHAT IMPACT will the European crisis have on the U.S?

EVEN IF the U.S. economy continues to gather strength, it could easily be caught in the downdraft of a European financial crash. That's the fear of economists of the club of the richest nations, the Organization for Economic Development and Cooperation (OECD), which in November published its Economic Outlook.

Their most optimistic scenario--which they call "muddling through"--calls for a recession in the euro area and continued high unemployment in Europe and the U.S. But they also point to the possibility of a disorderly default by Greece or other heavily indebted eurozone countries, with an impact that could be "catastrophic" as banks and other financial institutions failed as a result.

In mid-January, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) updated its World Economic Outlook by sharply cutting its forecast for world economic growth for 2012--in large part, the IMF said, because the world economy had entered a "perilous new phase" as the result of the euro crisis, which saw European banks increasingly reluctant to lend to one another for fear that they might not get their money back.

The world's advanced economies, the IMF predicts, will grow by just 1.5 percent on average in 2012-13--a rate it called "too sluggish to make a major dent in very high unemployment." The IMF's Global Financial Stability Report update was titled, "Deeply into the Danger Zone." And IMF Director Christine LaGarde has repeatedly warned of a "1930s moment," invoking the memory of the Great Depression.

World Bank economists also weighed in with a grim view, anticipating a devastating impact on most developing countries if the euro crisis spins out of control. They cut their forecast of world economic growth for 2012 from 3.6 percent to 2.5 percent--but estimated that the actual results could be much worse. While China and India will continue to clock high growth rates, the bank predicts, they are slowing significantly, which is having a wider impact on developing countries that export raw materials to China's industry.

"The downturn in Europe and weaker growth in developing countries raises the risk that the two developments reinforce one another," the World Bank economists write, concluding that "the global economy has entered a dangerous phase."

WHY CAN"T Europe find a way out of the crisis?

TO UNDERSTAND why, it's worth reviewing how this mess came to be.

The euro is the currency of 17 countries, with Germany at its core, and France, Italy and Spain the other major economies involved. It was launched in 1999, and for the mid-2000s, it seemed to work well, especially for Germany.

Having held down wages and created a more "flexible" labor market--that is, made it easier to fire people--Germany became the most competitive manufacturing exporter in the world, and profited enormously by selling equipment to booming Chinese industries. Germany also effectively served as the eurozone's banker through the European Central Bank (ECB), essentially financing its own exports to eurozone countries.

As long as countries like Greece, Portugal, Italy and Spain could borrow money at the same low interest rates as Germany, everything seemed fine. But then came the financial crash of late 2008, which compelled even small countries like Greece, Iceland and Ireland to assume the bad debts wracked up by their banks.

Since the summer of 2010, Greece has been pressured by the IMF, European Union and the ECB to take one round of austerity measures after another, aimed at extracting $500 billion that Greece owes on its government bonds. Despite a series of general strikes and mass protests, the Greek government has pushed through the cuts in exchange for bailouts totaling $300 billion.

The latest scheme for a "rescue" will involve bondholders accepting a "haircut" of at least 50 percent on the money that they're owed by the Greek government--which could blow a hole in the balance sheets of major European banks.

In any case, the downward spiral of the Greek economy--which has contracted three years in a row--means that even after the bailout, Greece's debt will still be more than 150 percent of GDP, higher than it was in mid-2011. After forcing the resignation of a Greek prime minister last year, Germany is now seeking to formally remove the Greek government's ability to make its own financial decisions, putting it in the hands of European bureaucrats instead.

But of course, the crisis isn't contained to Greece or other small economies like Portugal or Ireland. Spain, Italy and even France are under pressure because of their own mounting government debt and the higher interest rates they must pay. And the two European rescue funds--the European Financial Stability Fund and its successor, the European Stability Mechanism--total about $600 billion, a fraction of the money that would be necessary to bail out a big economy like Italy.

That's why in November, the interest rates Italy had to pay on its government bonds skyrocketed, prompting German Chancellor Angela Merkel and French President Nicholas Sarkozy to engineer the ouster of Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi and install technocrat Mario Monti in his place.

Still, the eurozone remained on the brink of a financial panic as banks refused to lend to one another in what appeared to be a replay of the crash of 2008. A meltdown was averted only when the ECB stepped in to offer banks three-year loans at rock-bottom interest rates, and agreed to relax the rules on how much capital banks have to keep in reserve. After borrowing nearly $500 billion from the ECB at that rate, banks are expected to borrow another $1 trillion in February--a sign of the crisis surrounding Europe's key banks.

The ECB maneuver gave Sarkozy and Merkel a window of opportunity to move forward on a new treaty that will give Germany greater authority over the finances of eurozone countries--but without obligating Germany to assume financial responsibility for further bailouts.

As Germany's attempt to dictate economic policy to Greece makes clear, any aid from other European countries will come with severe austerity conditions imposed by Berlin. Germany, by insisting on such measures in order to protect its own treasury and the viability of the euro, is actually driving Europe into recession.

WHAT ABOUT China? Can't its growth help boost the world economy?

FOLLOWING THE crash of 2008, China's economy revived quickly due to a massive stimulus program that aimed at building up the interior of the country and spurring domestic consumption to replace for the loss of export markets. China's growth in turn helped boost economies in Latin America, Africa and Asia, which, along with Germany and Japan, benefited from exporting to China.

While China's economy is now the world's second biggest, it is still far too small to replace that of the U.S. as the engine of world economic growth. And while Chinese economic growth this year is predicted to be a rapid 8.2 percent by the IMF, that growth is down from 10.4 percent in 2010 and 9.2 percent last year.

What's more, the Chinese economy is still geared overwhelmingly to exports to the U.S. and Europe, and has massive overcapacity in key industries such as steel.

Thus, a slowdown in the advanced countries will eventually hit China. At the same time, China is in the midst of its own housing and financial bubble and rising inflation, brought on by the efforts to pump up the domestic economy. No one knows what will happen when the bubble bursts, but a Chinese financial crash is certainly possible.

WHAT ARE the political implications of all this?

IN A word, revolutionary. In 2011, the world economic crisis was the context for the Arab Spring, the mass strikes in Greece, the indignados movement in Spain, and of course the Occupy movement in the U.S. While the struggles are of course on vastly different levels, there's a common root to them. Even in China, where the economy is growing, strikes are commonplace as workers fight for wages to keep up with prices.

At the same time, the international ruling class is worried about maintaining its legitimacy. When the Financial Times editors feel compelled to run a series titled "Capitalism in Crisis," you know the concerns are acute.

But it isn't automatic that the left will benefit from the crisis. Right-wing parties have made gains in Europe by linking populist themes to racist anti-immigrant appeals--and U.S. politicians like Newt Gingrich have taken note.

The challenge for the left is to link our criticism of capitalism to the effort to rebuild working-class organization in order to resist austerity and fight for a society based on human needs. The Occupy movement has shown the potential to take that struggle forward.