The burden of crossing over

examines the successes and tragedies of Whitney Houston.

THERE IS one major question that comes to mind with last week's tragic death of Whitney Houston: how the hell did this happen? How can someone with her perfect combination of talent and support fall so far?

She practically came from music royalty: daughter of Cissy Houston, cousin of Dionne Warwick, goddaughter of the great Aretha Franklin. Her first gigs in music were alongside amazing talents like Chaka Khan, Jermaine Jackson and Teddy Pendergrass.

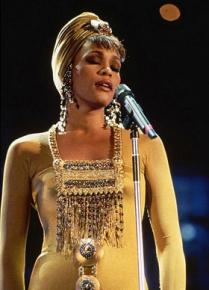

And, of course, there was that voice. At three-and-a-half octaves, she could hit notes that would make the Sirens green with envy. More that that, she knew exactly where to add a flourish from her gospel training and when to simply let the note breathe and be.

The high points of her career provided some staggering praise. According to the Guinness Book of World Records, she is the most awarded female artist of all time--30 Billboard Music Awards, 22 American Music Awards, six Grammys, and over 300 others! Over 170 million copies of her albums have been sold worldwide.

So once again, what the hell happened? How does an artist go from this to drug addiction, bankruptcy, a destroyed singing voice and death at 48? As always, there are a lot of potential answers in the time and place in which she made her music.

That place was the 1980s. Black Power and civil rights--movements that profoundly shaped the music of her family and colleagues--were past their prime. The music industry was regaining its footing. And just as Ronald Reagan was figuring out ways to get the African American movement in general under control, so were the record companies doing the same thing to soul and R&B.

It showed up in few artists' music more clearly than Houston's. There was never any question that her soul upbringing could be heard on her first two eponymous albums, and critics raved over her voice. Just as many, however, commented on how "poppy" many of her arrangements were. And indeed, nothing on these albums was released without the dictatorial approval of Arista Records head Clive Davis.

THIS WAS essentially the contradiction of the "crossover." Yes, there were plenty of boundaries broken down, plenty of white kids inspired by Black music that might not have otherwise. She was the first Black female artist to receive consistent rotation on MTV, opening the door for Janet Jackson, Anita Baker and others.

But at what price? She was derided as a sell-out in no time at all. Writers complained that the effervescent soul present during performances was totally lacking on her albums (and comparing live footage to those albums, it's hard to argue with that assessment). At the 1989 Soul Train Music Awards, she was booed after being announced as a nominee.

And so, just as the awards and album sales kept rolling in, the opposite directions of contradiction kept pulling on Houston's art. Earlier on in her career as a model, she refused to work with companies that did business with apartheid South Africa. By the time she was booked to play at Nelson Mandela's 70th birthday celebration in 1988, she had worked with Coca-Cola, one of the many companies that were subject to the global boycott movement.

Three years later, she was performing the "Star-Spangled Banner" at the Super Bowl during the first Gulf War. It was released as a single, and hailed as a quintessentially patriotic moment while America traded blood for oil.

Of course, asking one artist to bridge the rifts of a nation is beyond unfair, but the late 1980s and early '90s were times when the gap between America and African America was undeniable. On one side, there was a post-civil rights generation whose jobs were being shipped off, their communities terrorized by cops and blighted by unemployment.

On the other were Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush, willing to spend untold amounts of money on war and do business with South Africa while wagging their finger at Black "welfare queens." All the crossovers in the world couldn't bridge this gap, but there still seemed to be an expectation that Houston's music should somehow try.

It was around this time that Houston began what we know now to be an irreversible spiral: her tumultuous and abusive marriage to Bobby Brown, her financial troubles, her battles with addiction that eventually stole her voice away.

When she wasn't missing performances or showing up late to them, she was trying to hit notes that her ravaged vocal chords couldn't manage anymore. Though she made several attempts at a comeback, by the end of her life Whitney Houston was in essence a walking pop music cliché.

There is something more than a little eerie about Houston's death coming so close to that of Etta James and Don Cornelius. In a roundabout way, each represent three sequential phases in soul and R&B--their ascent in the wake of civil rights, their apex at the height of Black Power, and, with Houston, their re-appropriation by an industry whose concern for artists comes well after its monetary bottom line.

Speaking with Oprah Winfrey in 2002, Houston claimed, "The biggest devil is me. I'm either my best friend or my worst enemy." That may have been true, but it's worth wondering whether her own devils would have taken her down so soon if there hadn't been such oppressive expectations loaded onto her shoulders. An artist's concerns for being a media symbol or cash cow should come well after their concern for being human. Whitney Houston showed just how powerful and fragile such an existence can be.