“A movement has to control its own voice”

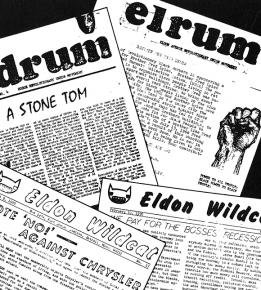

Dan Georgakas is co-author of the book Detroit: I Do Mind Dying, which tells the story of the Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement (DRUM). DRUM was launched in 1968 when Black autoworkers led a wildcat strike at the Dodge Main plant in Detroit--in a challenge not only to the auto bosses, but to racist union leaders.

The RUMs, which came to be known under the umbrella name of the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, represented the most radical wing of the Black Power movement. Within a few years, RUMs had spread around the city, to other auto plants, health care facilities and UPS.

Georgakas spoke to about the role that newspapers played in the organizing, in this interview originally published in the October 12, 2001, Socialist Worker.

IN DETROIT in the late 1960s, with so much political activity, newspapers played a critically important role. Why a concentration on newspapers?

Part of it was natural--newspapers are a way to communicate. But in terms of the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, it wasn't accidental.

In the mid-1960s, a group of African Americans were involved in a study group where they read of number of classic Marxist texts. One that struck strongly was a pamphlet by Lenin called Where to Begin--where he argues that a newspaper is the place to begin doing serious outreach to a mass audience.

If the newspaper can come out regularly with dependable news, slowly, a mass audience will follow it and begin to take direction from it.

John Watson and Luke Tripp, who both later become the leaders of the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, were the major forces in putting out the Inner City Voice--an independently produced Black newspaper.

Wayne State University, Detroit's city university, had a newspaper called the South End, which came out five times a week. Using the means by which editors are elected to that post, the ICV's editor John Watson became editor of the South End--and transformed it into a radical daily.

They put black panthers on the masthead and added a sub-logo, "One Class-Conscious Worker Equals 100 Students." This wasn't a putdown of students, but an equation about power. They were making a statement at the end of the 1960s, not that students weren't important, but if you wanted to change society, you had to organize workers.

Of the paper's 10,000 daily circulation, half the papers were given away off-campus--in particular, at the Dodge Main auto factory.

They also had fraternity pages, sports pages, fashion pages, because the people who read these articles were students, too--and maybe they'd also read the news.

They were unabashedly socialist in their approach.

At this time, there was an insurrection at Dodge Main, led by Black workers who made up 85 percent of workers and yet were 2 percent of the stewards and 2 percent of foremen. So the paper called for immediate reforms in terms of representation of stewards and foremen and the speed of the line. But in the context, it raised questions of workers' control of the means of production.

They took on any problems that existed in the city of Detroit, such as the hospitals or education system, and addressed them from an explicitly socialist point of view. They did letters to the editor and had counter-columns. And they took on foreign policy issues, such as Israel, or the anti-junta struggle in Greece.

It was considered essential for a movement for social change to have control of its own voice and to be able to bring its message undiluted to the public.

The South End was widely read. They would drop papers off at various points--at a housing group, or when there had been labor unrest at UPS.

They targeted people who were already saying that something's wrong--and gave them a direction.

It's very important to say how unapologetic they were about their point of view--but at the same time not bombastic. They felt that if you presented things often enough--saying that this is unjust, here are the facts and the figures--you could get people listening in places you weren't necessarily expecting.