A strike call that won’t call a strike

Seattle teacher and activist explains why he thinks the call for a May 1 general strike is the wrong step for the Occupy movement.

ON SUNDAY evening, Occupy Seattle's General Assembly voted overwhelmingly to endorse a call for a general strike on May 1. The subject had been the center of contentious debate in the GA since the week prior when it was proposed.

I was one of a handful of people present who voted against the proposal. I might have expressed my viewpoint then if the facilitators had taken measures to ensure that opposing views were at least more proportionally represented. My reasons are as follows.

As a socialist, I think an economic system that profits off of the exploitation and oppression of those who produce the wealth needs to be replaced with a true democracy from below. I think that a key mechanism to bring that about is workers striking to stop that system and protect themselves from the worst excesses of the free market.

I want to see more strikes--and ultimately, general strikes. This is crucial both to rebuilding the labor movement in this country and ultimately changing a system where the 1 percent profit off the 99 percent.

However, I worry that most of the 99 percent won't heed the call to strike on May 1.

This is important for a couple of reasons.

The first is that strikes don't mean much if whole workplaces don't go out. Even if you take the day off, if your coworkers aren't organized to walk out with you, it isn't much different to them than you calling in sick. The second reason follows that if people won't come out on May Day for a general strike called by Occupy, then many people will perceive the Occupy movement's influence as waning, which will make it more difficult still to build the movement and continue to challenge the 1 percent's rule.

Considering that Occupy events as of late have been a fraction of the size they were last fall, the question of how to expand Occupy to more of the 99 percent should be the heart of this debate.

Those who proposed the general strike argue that in order to draw more people in, more radical actions are needed. As a teacher, I learned that in order to challenge students effectively, we need to consider whether what we are teaching is beyond the students' Zone of Proximal Development. That means if we ask them to try something that is too far out of their comfort zone, we risk losing their attention or interest, as they may feel it's beyond their comprehension or ability.

A general strike might be a bit too far out of the comfort zone for most people in the U.S., where last year, there were fewer than 20 strikes involving 1,000 workers or more, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

No doubt there are many workers who would like to go on strike against their employer and problems at their workplace. But the question is whether they have the confidence that anyone else they work with would strike with them.

I WOULD venture a guess that there were few if any people at Seattle's GA Sunday who have even been in a strike, much less organized one. There are many lessons learned from being in a strike--like strategies to build up support in a workplace or knowing how to effectively challenge the employer if they try to prevent or retaliate--that are needed to successfully organize a general strike. Unfortunately, the vast majority of workers in the U.S. just don't have any experience with them.

These things and more need to be learned by many more working people before we are likely to see national general strikes in the U.S. A country like Greece, where there have been numerous general strikes in the last two years, has a much higher unionization rate than the U.S. and a tradition of working-class militancy that goes back to the struggle to overthrow a military dictatorship.

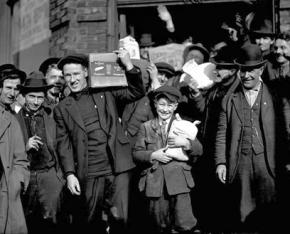

The last time there was a general strike in Seattle, in 1919, more than 100 unions involved. They organized a strike committee with three representatives from each to prepare for the strike and coordinate it once it was under way. Striking workers had a plan to deliver essential services to people outside for-profit structures.

At the GA in Seattle last Sunday, many of the most vocal supporters of the proposal argued that the general strike call is the first step toward achieving a general strike in the future--or even that the term general strike can mean something else entirely from what it has for radicals over the decades.

The danger in calling a general strike when it likely will fall flat is that this further delegitimizes the strike as a tactic for working people looking to fight back. This is even more likely to happen when a small number of people attempt to disrupt production--through blockades or pickets of workplaces--but haven't made the effort to win support from the majority or even a significant minority of the people who work there.

Perhaps this is what is intended when some radicals argue today for "disrupting the system" or redefining the term "strike" so that a strike doesn't necessarily need the support of workers involved. This runs counter to what socialists see as the key feature of the strike--the collective struggle of workers to stop production in a workplace, which can break down divisions among them and helps workers see their potential to affect larger change.

The Occupy movement in Oakland, Calif., did make a call for a general strike after a police attack on its camp that nearly killed Iraq war veteran Scott Olsen. The day of action on November 2 involved tens of thousands of people and was an inspiring and important show of solidarity against the repression of Occupy.

But it would be wrong to say that the successful day of action was a general strike, like the one that took place in Oakland in 1946 or the one in Seattle in 1919--which were based on the coordinated and collective action of large numbers of workers to stop production.

I would like to see a true general strike of millions of people across the U.S., collectively taking a stand against the greed of the 1 percent. However, as a history teacher and a union activist, I know that hope and passion--though they are important ingredients for change--will not bring about a mass movement.

The continued attack on working-class living standards the world over, while business profits get bigger, will push more and more people to question the priorities of our society. But that alone won't bring about a general strike. It will also take the hard work of organizing, reaching out to even wider layers of the 99 percent who haven't been mobilized yet to channel working-class discontent into activism and show workers they have the power to change capitalism's priorities.

Hopefully, in the process, we'll push the comfort zone leftward--and see more workers striking to win their demands.