Why we’re still marching

Fifty years after the historic March on Washington, the struggle for justice continues.

THE 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom is one of the most famous moments of the 20th century. Every schoolchild learns about Martin Luther King's "I Have a Dream" speech. The image of the crowd in front of the Lincoln Memorial, packed into every available space around the Reflecting Pool, is instantly recognizable.

But this high point in the struggle for justice is almost always treated as a matter of history--a powerful, important, inspiring event, yes, but one that belongs to the past. After all, we're told, King and the civil rights marchers were challenging a system of legalized segregation where Blacks had to sit at the back of the bus--whereas in the United States of the 21st century, a Black man sits in the Oval Office.

But 1963 and 2013 are not so very far apart. Many of the strongly felt demands that brought a quarter million people to Washington, D.C., 50 years ago remain unfulfilled. King's dream of a society rising "to the sunlit path of racial justice" remains just that: a dream, not a reality.

The murder of Trayvon Martin last year and the acquittal of his murderer George Zimmerman last month are further proof that the struggle to achieve the dream must continue. The fact that Martin died because a self-appointed neighborhood watchman decided he didn't belong in a gated community in central Florida after dark would be grimly familiar to the civil rights marchers of 50 years ago. So would the fact that Zimmerman got away scot-free after stalking and shooting an unarmed Black teenager.

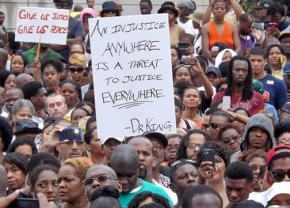

There were already plans in the works to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington in late August. But the not-guilty verdict delivered by the nearly all-white jury in Sanford, Fla., has given that commemoration an urgent purpose--to send the message, loud and clear, that racism is not a thing of the past, and that it's time to confront it in the here and now.

Like Martin's killing last year, the Zimmerman verdict not only outraged millions of people, but caused a surge of protest and activism in numerous cities. Organizing for the August 24 anniversary events in Washington and elsewhere can be another step toward focusing that anger and discontent.

Those who want to follow in the footsteps of the civil rights movement today should use this opportunity to deepen the connections between the people who are beginning the work of challenging the many faces of racism and injustice in the U.S. today.

THE MARCHERS of 1963 did bring about a different society through their struggles. Having an African American president would have been inconceivable in a previous era. The civil rights movement did break the back of Jim Crow segregation and opened opportunities for Black Americans in many different social spheres.

But for all the signs of progress achieved by the civil rights movement, it's also clear that racism continues to deform American society.

By just about any measure, African Americans suffer economic, political and social discrimination and disadvantage. Blacks are 13 percent of the population, but account for 39 percent of the U.S. prison population. In economic good times and bad, Black unemployment is roughly twice the overall average--and in the wake of the Great Recession, joblessness and poverty afflict African Americans in many urban areas at levels not seen since the Great Depression.

All of this was true months ago as preparations for the 50th anniversary of the march began. But events of the last few months--not only the Zimmerman verdict, but the U.S. Supreme Court's blow to the Voting Rights Act, one of the main achievements of the civil rights movement--have given the August 24 demonstration what King, in 1963, called "the fierce urgency of now."

Rather than remembering 50-year-old speeches and slogans, marchers this year will have immediate questions on their mind, too--stopping restrictions on voting rights, repealing the racist "Stand Your Ground" laws in place in nearly two-thirds of the 50 states, confronting the continuing crisis of unemployment and poverty.

Of course, the experience of the struggle is very different for marchers in 2013. The 1963 march was a landmark for a movement that already involved millions of people. It was a national crescendo after almost a decade of civil rights advances and defeats, beginning in Montgomery and Little Rock, and passing through Greensboro and McComb and Albany and more. Among the marchers in Washington were tens of thousands of people who had sat in at lunch counters, registered voters, organized against job discrimination and endured beatings by racists.

Today's march will start from a much lower level of organization and activity. Much of the widespread anger at Trayvon Martin's killing never got turned into action. Activism around this and other racist outrages has tended to rise and fall quickly. Thus, the protests against Martin's murder last spring helped inspire intense campaigns to win justice for the victims of police violence, in New York City, Chicago and Oakland, to name a few places--but it was difficult for these localized initiatives to link up nationally or maintain ongoing organization.

So the anti-racist struggle has a far less definite shape in 2013. But that's all the more reason to seize the opportunity of the national mobilization this August--to bring the struggles that are taking place into contact with each other, to connect the networks of people who responded to the Zimmerman verdict in different cities, and to draw those who are new to activism into more regular activism.

THE LEADING forces involved in this year's March on Washington will be mainstream civil rights organizations like the NAACP and National Action Network (NAN). SocialistWorker.org has been critical of these groups at many points in recent years, particularly when they avoided challenging Barack Obama and his administration for failing to take any action on issues affecting Black America.

At a press conference in July, Obama spoke powerfully about his reaction to the Zimmerman verdict, the issue of racial profiling and even the "history of racial disparities in the application of our criminal laws." But the remarks were most notable because Obama has said almost nothing about these issues during his presidency.

Black America has suffered the brunt of the economic crisis, a generation of young Black men is still being criminalized by the New Jim Crow, a social crisis is tearing apart the poorest African American neighborhoods in big cities, one state after another is trying to resurrect restrictions on Black voting rights not seen since long before 1963--and the country's first Black president has been silent.

And what's more, Black political figures--with some brave and honorable exceptions--have defended the silence.

Rev. Al Sharpton, the leader of NAN, spoke out after the Zimmerman verdict, and NAN called for vigils on July 20 that brought out people in more than 100 cities. Yet Sharpton led the attack against African American critics of Obama like philosopher Cornel West and talk show host Tavis Smiley when they dared to speak out--during the 2012 election campaign, no less--about Black poverty and the need to challenge racism.

No one should forget this record. But it's still a welcome development if mainstream groups put resources into organizing for August 24.

First of all, this will widen the mobilization, both for the Washington march and for anti-racist demonstrations generally. The experience of the July 20 vigils called by NAN, for example, is that they brought out a range of people who hadn't gone to earlier protests. It's all to the good if participation in anti-racist protests is bigger and broader.

Plus, groups like NAN and the NAACP or political figures like Sharpton and Rev. Jesse Jackson are talking and acting in ways that will lead their supporters to question why they refused to speak up before, why they avoided action before--and, now, why they want to limit the aims of this march and future mobilizations so that Obama and the Democrats aren't put on the spot.

That's another certainty about the March on Washington: The Obama White House will put pressure on march organizers to avoid criticism of the president and focus their speeches on attacking the Republican Neanderthals, to downplay institutional racism and go along with the mantras about individual responsibility.

All this dovetails with the agenda that mainstream civil rights groups have followed for years. They won't suddenly transform themselves for August 24.

But it's also true--as is so often the case for big demonstrations--that the speeches from the platform in Washington will be less important than the convictions and aspirations of the thousands of people who will attend the march.

For them, the March on Washington will also be about their decision to attend, the discussions they were involved in before the demonstration and on the way there, the connections they make with other marchers, and the commitment they will hopefully make to stay active after August 24.

Fifty years after the civil rights movement's historic March on Washington, we still need to be marching against racism and injustice. The not-guilty verdict in Sanford, Fla., gave us a bitter example of what happens when bigotry and hate aren't confronted. But the great legacy of the 1960s struggles provide an inspiring glimpse of what we can achieve when masses of people organize to fight for a better world.