The dungeons of California

A hunger strike in prisons across California has entered its second month, and the remaining participants are mourning the first casualty of this action. Billy "Guerro" Sells was found dead in a Corcoran prison isolation cell on July 22, 14 days after he began refusing food. Sells' death has been ruled a suicide, but supporters of the hunger strikers "still think the [California Department of Corrections] is responsible for what happened to him," said Donna Willmott, a representative of the Prison Hunger Strike Solidarity Coalition.

This year's hunger strike was preceded by two three-week strikes in 2011, but many more prisoners took part when the action began on July 8. Some 30,000 refused meals and 2,300 refused work or educational assignments in 24 of 33 state prisons and all four private, out-of-state facilities where California sends inmates. According to state prison officials in a statement released on the one-month anniversary, 349 prisoners had refused the last nine consecutive state-issued meals, and 193 haven't eaten at all since the hunger strike began.

The prisoners have five demands addressing questions such as administrative abuse and adequate food. But the grievances center most of all around indefinite solitary confinement in the prisons' Security Housing Units, commonly called SHUs. According to the UN's Special Rapporteur on torture, solitary confinement for more than 15 days constitutes torture--yet California prisoners routinely remain in SHUs for years or decades. talked to a teacher who works with an educational program at Pelican Bay State Prison. The teacher requested to remain anonymous to avoid being restricted from teaching in the prison.

WHAT KIND of people end up in the Security Housing Units, and why?

OFFICIALS SAY inmates are put in the SHU because they're gangbangers and "shot-callers," calling murders on the streets. But actually, as an inmate I know puts it, anybody can end up in the SHU for the slightest infraction.

Prison officials make all the decisions about who goes in and out of the SHU. It's about exercising control over the inmate population. According to one study, a prisoner who is determined to be a gang member or associate spends an average of six years in the Pelican Bay SHU. That's how you end up with people there for decades. They hang it over the heads of everybody at Pelican Bay and prisons statewide--everybody knows about the SHU. As a mechanism to control California prison system, there's nothing like it.

TELL US about the conditions in the SHU.

THERE ARE thousands of guys in there, in three or four different wings, and everything looks exactly the same. There are sections of pods, in two tiers. The rooms are small--although not as small as ad-seg [the more traditional solitary confinement]--and everything is all-white.

In each cell, there's a cement bunk, with a mattress, which the prisoners lift up during the day to have something to sit on, a tiny desk and a toilet, so it's self-sufficient, and they never have to leave. They never get any direct sunlight, they're never outside. And they don't bunk up, they're always alone.

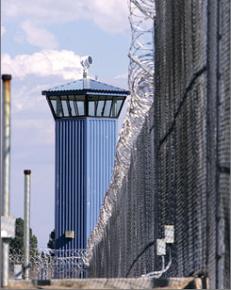

So Pelican Bay has a prison within a prison--a maximum security facility within maximum security. If you're looking for something similar, you could maybe compare it to the Tamms Supermax prison in downstate Illinois, which was officially closed at the start of this year after a long struggle.

Pelican Bay is already the most locked-down prison in California, and within that, you have the Security Housing Unit, which is even more secure. Ad-seg at least has appeal processes. These guys in SHU are just in there, stuck. There's limited programming in the SHU--prisoners can get educational programs, but they never get out into a classroom or see a teacher more than one at a time.

There should be a real step-down program. Prison officials will tell you they have one, but they need one where inmates can come out into the general population, maybe after a year of doing an associates' degree program, if it's going well. But right now, in order to get out, they have to "debrief"--which means to snitch, which threatens their lives. The choice is: I rat on people and I'm dead, or I'm stuck in horrific conditions for what could be the rest of my life.

And people come straight out from these conditions onto the streets. People in California, the public, should be concerned that people living in conditions of sensory deprivation are released straight into the community, with no rehabilitation whatsoever.

HOW HAVE prisoners been able to organize in these conditions?

IT'S AMAZING how creative human beings are. They'll find ways to communicate in the most extraordinary circumstances. They can "go fishing," which means to throw these lines out of their cells with messages attached. Prison security has put plastic obstacles on the floor to stop them from being able to communicate this way, but prisoners do anyway. They can communicate inside the pods, because they're next to each other--they can talk to each other through the doors.

The prisoners in Pelican Bay aren't allowed newspapers. San Quentin has an inmates' paper, but in Pelican Bay, they're not allowed to have that. But a prison is like a beehive--if you say one thing, by the end of the day, it's reached the entire prison. Some inmates also have TVs, too.

DO YOU have a sense of how many prisoners have been involved in organizing for the hunger strike?

I'M NOT sure. The hunger strike started out large--much larger than the previous one in 2011. The last report I got was that it had dwindled, with only about a few dozen hunger striking continuing in Pelican Bay. That was three weeks ago, and they were saying the was going to end soon, and I'd be able to go back in to teach. But that didn't happen, and the prisons have stayed on lockdown.

WHAT'S THE relationship of prisoners who aren't in the SHUs to the hunger strike?

PELICAN BAY is extremely locked-down in every way, so be there in any way is a difficult situation. The prisoners might not be in solitary, but they need more programming themselves.

Then there's High Desert, in Northeastern California. Guys would prefer to go to Pelican Bay rather than High Desert, which has been going on and off lockdown because of the hunger strike. Those are the young guys. The prison officials try to separate out what they call the soldiers from the shot-callers--the older guys they put at Pelican Bay, and the young guys, who they say were soldiers on the ground, they put in High Desert. There's hardly any programming, and every movement is controlled.

You can tell what it's like when you go out into the yards at these places--both yards have these chain link fences, which break the space up into these narrow, small areas.

IS THERE a central thrust to the organizing, or is it more of a diverse bunch of people, all with their own demands?

MY GUESS would be that there's a central thrust to the organizing among a core of smart, experienced people, but that the organizing and their demands about the SHUs tap into the needs of so many other prisoners that they're bringing in a lot of other people who are not only in solidarity with them, but also have their own grievances.

Prisons in California are horrific. The hunger strike may be centered among the old guys who've been there for decades and decades, and are more savvy about organization, but they're definitely tapping into widespread injustices throughout the system.

There's also the larger context that explains the timing for this kind of organization. With Assembly Bill 109, the legislation that passed in 2011 because of medical issues and overcrowding in the prisons, the state of California has been forced to release tens of thousands of inmates. This has created a fluidity throughout the prison system, with Level 4s moving to Level 3, and Level 3s to Level 2. People who normally wouldn't have been able to get out are getting out. A woman I met at Chowchilla just got out after 33 years. It's extraordinary that she was able to see the light of day again.

The call for rehabilitation is growing. California is still in a budget crisis, the prisons are part of that crisis, and there's a $30,000 to $40,000 annual expense for every inmate. Some people are doing time for non-victim, nonviolent drug crimes, and if these people could be released and rehabilitated, the state would save billions of dollars. I'm sure the organizers of the actions inside the prisons are very aware of this.

But prison officials aren't going to want to give an inch to these inmates. It's going to take a lot more struggle. It's going to take organizing and solidarity from people outside to change anything: linking up advocacy organizations, having demonstrations, lobbying state officials, petition drives, door-to-door community work and old-fashioned grassroots organizing throughout the state.

We need to raise the profile of what's happening and get out pictures of the hunger strikers everywhere. They've dehumanized these people, so we have to show that they are human beings and could be anyone. Their lives are being thrown away, and they have families, children, communities. They're all poor and working class, and they're predominantly Black and Latino.

They've been subject to a vicious scapegoating campaign. Taxpayers have been lied to. And so people turn a blind eye, while inmates are being tortured--sensory deprivation is torture. Future generations will look back and say: How could you do that? How could you throw someone in a box for 30 years?

The reformers won in Illinois a decade ago and forced the governor to issue a blanket commutation for all 167 people on death row. That was won by putting a face on the people who had been tortured, so the state couldn't get away with its dirty secret anymore. It can happen.

THE HUNGER strikers aren't asking to be released or even for the SHUs to be eliminated. Why won't the state just grant the hunger strikers' five demands?

IT'S ABOUT control over the prisons. If the state concedes on any demand, that can send a message that organizing works, and the state may be afraid of that.

What's interesting is that after the last hunger strike, we started getting education programs into the prisons again. Things changed at Pelican Bay after the last hunger strike--minor changes, minuscule compared to what's needed, but there's more programming and a new warden. So even though I'm sure they're afraid that it sends the wrong message if they give in, with enough support for the hunger strikers, they might not have a choice.

The situation is so bad that people may be willing to die. Hunger strikes are dangerous, dangerous things. People forget that, but people are starving themselves to death. If people are willing to give up their lives, that says something about the conditions they're living in. We're not talking about medieval prisons. We're talking about something modern-day--these "clean, white, shiny hells," in Mumia Abu-Jamal's words.

The prisoners need more support outside. What would be great is if education institutions could get behind them. Many colleges are already involved--UC Berkeley supports San Quentin prisoners and helps with their newsletter. There's something to tap into. My idea is we should have a whole re-entry program, using the community colleges--we should convince them to bring in inmates as students. Then you'd start to have more institutional supports, plus bring more students into the prisoners' struggle.

This hunger strike is going to end. There may be some improvements--hopefully there will be. But there will still be solitary confinement throughout the state of California. We need to plan ahead for the next fight, too.