Upsized classes, downsized education

With class size looming large among the issues in the Portland teachers' contract fight, New York educator dispels the myths of the corporate school reformers.

ONE OF the most glaring contradictions in today's debates about public education is the fact that people who are fantastically wealthy or politically powerful--or both--advocate for models of public education that are profoundly different from what they choose for their own children.

In 2011, then-New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg told an audience at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology that the only thing that matters in education is the "quality of teacher." Thus, he concluded, other reforms, such as reducing class sizes, aren't important.

Bloomberg said his ideal would be to cut the number of teachers in New York City in half, double the compensation of those who remained--and double the size of all classrooms. "[D]ouble the class size with a better teacher is a good deal for the students," Bloomberg declared.

But it certainly wasn't a good deal for Michael Bloomberg's daughters, both of whom attended the Spence School in Manhattan. According to the school's website, there are only 17 students per class in the lower grades and 14 in the middle and upper grades. Annual tuition is $40,975 per student.

At the time Bloomberg spoke, average class sizes in New York City public schools, according to the New York City Department of Education, were 24 in elementary schools, 27 in middle schools and 26 in high schools. That means at time he was standing at the podium and lecturing about the wisdom of doubling class sizes, middle school students in public schools were already attending classrooms that had twice as many kids as those Bloomberg's daughters attended.

In Chicago, Mayor Rahm Emanuel has closed more public schools than any other official in U.S. history -- more than 50--after just two and a half years in office. An investigation by the Chicago Tribune showed that the city's decisions about school closings were based on an "ideal" class size of 30.

According to the Chicago Teachers Union, the average class size in city schools is 28. Chicago has the fifth-largest average class size in high schools in the state of Illinois, the CTU reported--and "Chicago's average class sizes at the early childhood grades (K-1) are larger than 95 percent of all Illinois school districts."

But Rahm Emanuel's three children wouldn't know about that. They go to the University of Chicago Lab School, which charges $28,290 per student per year in tuition. In the lower grades, the Lab School has 15 full-time homeroom teachers (who teach the core subjects) for only five homerooms of 23 students each.

The school advertises the fact that middle school students have the opportunity to meet in "[s]mall advisory groups" that "give students a chance to talk about issues with each other and an advisor in a non-judgmental setting." By the time they get to high school, Lab School class sizes are down to 18 pupils.

EMANUEL'S FORMER boss back in Washington, D.C. sends his children to private school, too. President Barack Obama pays $35,288 for his two daughters to attend Sidwell Friends School in Washington, D.C. The school has class sizes that range from 11 in pre-K to 12 in 8th grade and approximately 13 in high school years--roughly half the size of classes in the city's public schools.

Obama has spoken out publicly in favor of reducing class sizes. Yet Arne Duncan, the man Obama appointed as education secretary, has repeatedly argued that while parents usually prefer smaller class sizes, "[m]any high-performing education systems, especially in Asia, have substantially larger classes than the United States." In 2010, he spoke before a National Governors Association meeting and recommended that they look into "modest but smartly targeted increases in class size" as a way to save money.

One of the wealthiest men in the world, Bill Gates, is also extremely influential in education policy. Gates has used his billions to promote education "reform" ideas that he likes--including the Common Core Standards and charter schools.

In a 2011 Washington Post op-ed article, Gates echoed fellow billionaire Michael Bloomberg in arguing that teacher quality "trumps" all other considerations. "One approach is to get more students in front of top teachers by identifying the top 25 percent of teachers," Gates wrote, "and asking them to take on four or five more students."

Meanwhile Gates sends his three children to Seattle's Lakeside School, where class sizes average only 16 students. For a mere $28,500 per student per year, the school's brochure boasts of "an environment that promotes relationships between teachers and students through small class sizes."

Responding to Gates's article in the Post, Danny Westneat, a Seattle Times columnist and public school parent, wrote:

Bill, here's an experiment. You and I both have an 8-year-old. Let's take your school and double its class sizes, from 16 to 32. We'll use the extra money generated by that -- a whopping $400,000 more per year per classroom -- to halve the class sizes, from 32 to 16, at my public high school, Garfield.

In 2020, when our kids are graduating, we'll compare what effect it all had. On student achievement. On teaching quality. On morale. Or that best thing of all, the "environment that promotes relationships between teachers and students."

HOW DO we explain this pattern? Why are these people discrediting small class sizes for public school children, and yet choosing small classes for their own children?

Without speculating about their intentions, we can observe that their actions regarding our children fit with the policies of the political and economic elite as a whole. The emphasis on raising class sizes is in keeping with a general attack on public education and changes in the economy over the last 40 years often referred to as "neoliberalism."

Components of the neoliberal agenda include privatization, deregulation, free-market solutions for social problems, and union-busting. If you read authors David Harvey or Naomi Klein--or, in the field of education specifically, Lois Weiner and Pauline Lipman--you begin to see that globally, this restructuring is aimed at restoring and increasing profitability in general, and removing any social or ideological obstacles to profit.

This push for privatization of our schools is not a conspiracy. It's happening in the open and has emerged as the consensus among America's elites over decades of trial and error.

Through their committees, conferences, think tanks and other means, they have groped toward a policy that would help them bring education in line with the changes they are pushing through in the rest of the economy and society. Unionized teachers represent a major obstacle to this restructuring, and that, more than psychology or personal proclivities, explains why people like Bloomberg and Emanuel have made teachers the object of so much scorn and scrutiny lately.

The attack on unionized teachers is absolutely essential for the rich and powerful because it weakens the labor movement in general and, in the context of a recession, strengthens the hand of government officials as well as large employers everywhere.

Meanwhile, opening up the enormous K-12 education sector to entrepreneurial activity holds out the promise of new business. Forcing all providers and participants in public schools to live and die by standardized test scores allows politicians and education reformers to fall back on an easy defense: They are simply insisting on high quality in schools, as measured by test scores.

They won't accept failure, they won't accept excuses. How noble of them!

This attack on public education isn't about improving teaching and learning. As labor journalist Lee Sustar has pointed out, unionized teachers are facing a process nearly identical to the one that broke the back of the United Auto Workers.

The auto workers faced plant closures, teachers face school closures. They got outsourcing to non-union plants, we have charter schools. They faced the introduction of tiers in their contracts to pit older auto workers against newer ones, we have Teach for America, which continues to be the preferred provider of employees in several major American school districts. Corporate education "reform" is not an education policy so much as it is a labor policy, an economic policy.

THIS BRINGS us back to class size. One of the historic tactics that capital has utilized to defeat the power of working-class organization is to use fewer workers to do the same work.

Education is an extremely labor intensive process, and just as the crushing of auto workers or steel workers or miners required using technology to dramatically reduce the number of employees in these sectors, so, too, are today's corporate education "reformers" desperate to discover teaching methods or management techniques or websites or "apps" or anything else that will allow fewer people to teach more students.

On the other hand, reducing class sizes would not only require a redistribution of wealth from their priorities to ours, but would increase the size of the unionized teaching force, and thereby strengthen the hand of one of the largest sectors of organized labor in the country--and potentially unions in general.

That's why the powerful education "reform" crowd can't accept the idea that smaller class sizes are important. They are operating under a collective imperative to take advantage of the opportunity afforded by the recession to weaken organized labor--and therefore cannot seriously entertain proposals that violate their mandate, even if they would actually improve teaching and learning.

Research shows the benefits of smaller class sizes. And there is plenty of it--see the Class Size Matters website for examples.

The experiences of teachers confirm the research. In Los Angeles, where class sizes for English and math classes in 11th and 12th grade shot up to an average of 43 students in 2011, teacher Rachel Maher told the New York Times: "They say it doesn't affect whether kids get what they need, but I completely disagree...If you've gained five kids, that's five more papers to grade, five more kids who need makeup work if they're absent, five more parents to contact, five more e-mails to answer. It gets overwhelming."

But neither research nor experience will convince the 1 Percent to bestow the same resources on the 99 Percent that they unanimously give their own children.

Over the last several decades, well-funded conservative (and, increasingly, liberal) think tanks and researchers, along with their colleagues in the media have honed arguments to convince themselves and the public that privatization and union-busting is all for the best. Just as they have reasons--and research!--supporting the idea that cutting welfare benefits people on welfare, so too have they built up "proof" that larger class sizes could actually be better for our children.

That's how political leaders can continue to insist that everything they are doing amounts to an improvement in education. We don't have to call into question their motives or psychology to understand the double standard of sending their own children to schools with small classes and preaching larger ones for the general public. Those are the priorities of the ruling class, and any private doubts or public disagreement can be assuaged by the reassuring narrative about how the "quality of the teacher" is all that matters.

With the new Common Core Standards, corporate reformers can claim to be fighting for excellence across the board by insisting that all students perform to these standards. But notice that there is a standard for performance--but no corresponding "common" standard for resources.

There are Common Core standards for reading performance, but no corresponding standards for access to books and school libraries. There are Common Core standards for science performance, but no corresponding standards for the provision of laboratories with actual scientific equipment.

Focusing on performance standards allows the corporate reformers to blame or shame (or both) any school, any teacher, any student for failing to measure up. Focusing on resource standards, on the other hand, would call into question what political leaders do or do not provide to schools, teachers and students--and that raises the danger that they would be blamed for not measuring up.

IN OUR society, making sure powerful people avoid blame for social problems is always a priority. In the era of budget cuts, austerity, layoffs, and rising poverty the search for social scapegoats has intensified.

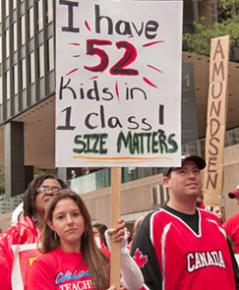

But there is also resistance--organized groups of teachers and parents putting up a fight for smaller class sizes. In late January, teachers in Portland, Ore., were preparing to go on strike as contract negotiations with the city broke down.

In 2013, the Oregon Parent Teacher Association newsletter reported that the state had the third-largest average class sizes in the nation. Statewide class sizes are difficult to measure, but relatively high teacher-student ratios--an imperfect proxy stat for class size since many teachers are actually out-of-classroom personnel--measured by the state and U.S. Department of Education seem to back up that claim.

In January, the Portland Student Union presented the school board with a document they called "The Schools Portland Students Demand," articulating their own vision for education . The first item on their list of 10 changes they wanted to see: "Class sizes less than 20".

Portland educators agree. As Hyung Nam, a history teacher at Wilson High School, said:

We just can't work and students can't learn under these conditions. All high school teachers were made to teach an extra class, so there are many teachers who have over 200 high school students. So imagine assigning an essay, and if you were to spend just five or 10 minutes grading each essay, and you have 200 essays--I mean, it's just overwhelming. It allows for less planning, or even getting to know your students. It's just an incredible amount of work.

[The school board] either has really no idea what it's like, or they don't care...This is a matter of survival. We can't teach under these conditions.

Across the country, the fallback position of politicians is the refrain: "We can't afford to reduce class sizes." But budget cuts are always about political priorities, not absolute sums of money. A CTU review of the 2012 budget for Chicago Public Schools, for example, found that the city set aside $351 million to expand charter schools, while the cost of reducing class sizes from 28 to 20 would be only $170 million.

Likewise, the PAT reports that the Portland Public Schools are sitting on a $29.9 million surplus, while the cost of the teachers' proposal for reducing class sizes would amount to between $11 and $14 million.

Teachers, students and parents know from personal experience that class sizes matter a great deal. Most of our "leaders" say the opposite, but they choose small class sizes for their own children. Their actions only prove what we all know to be true: Giving every child a great education means equipping every teacher, student and parent with great resources.