Songs for a socialist future

reviews a collection of songs by Irish revolutionary James Connolly.

EXPLAINING THE purpose for the publication of Songs of Freedom in 1907, James Connolly wrote:

No revolutionary movement is complete without its poetical expression. If such a movement has caught hold of the masses, they will seek a vent in song for the aspirations, the fears and hopes and hatreds engendered by the struggle. Until the movement is marked by the joyous, defiant, singing of revolutionary songs, it lacks one of the distinctive marks of a new popular revolutionary movement; it is the dogma of a few and not the faith of the multitude.

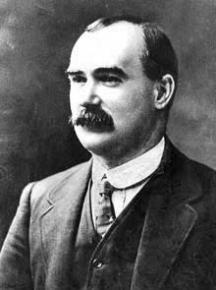

Connolly had grown up in an impoverished Irish working-class neighborhood in Edinburgh, Scotland, where he became active in the socialist movement. He spent seven years in the British Army before moving to Dublin, Ireland, in 1896 to found the Irish Socialist Republican Party.

Poverty took him and his family to the U.S. in 1903 where he organized with the Socialist Labor Party, the Socialist Party and the Industrial Workers of the World. He returned to Ireland in 1910 to play a leading role in the Great Dublin Lockout of 1913-14 and the Easter Rising in 1916.

He was executed by an English firing squad for his role in the Rising, but his legacy has been an inspiration to activists ever since. Connolly hoped that striking a blow against British military rule in Ireland during First World War could set ablaze an international struggle against imperialism and capitalism.

CONNOLLY IS best known for his political and trade union organizing in Ireland and the U.S. Some of his political contributions such as Labour in Irish History and Socialism Made Easy are still widely read and of lasting significance. Connolly emphasized that the fight for socialism in Ireland had to be tied to the struggle for liberation from English rule.

Connolly argued that only the Irish working class had an interest and the capacity to fight for an Irish Republic. He advocated for a workers' republic and warned that the mere transfer of an Irish flag for an English flag would fail to bring about freedom and equality. He fought for class unity among Catholic and Protestant workers on the basis of common interests; he opposed sectarianism and the partition of Ireland because of the impact it would have on the prospects for working class solidarity.

Connolly is much less well known for his cultural contributions. In the introduction to Songs of Freedom, Connolly gives as the second purpose for the collection's publication a very clear political motivation:

This is no spirit of insularity, but rather is meant as an encouragement to other Irishmen and women, to take their part and do their share in the upbuilding of the revolutionary movement of the Working Class. Most of these songs were written in Ireland, by men actually engaged in revolutionary struggle, of their time, whatever ruggedness may attach to their numbers is due to the fact that they were born in the stress and strain of the fight, and not the scholarly seclusion of study.

During Connolly's time in the U.S., from 1903 to 1910, immigrants, a large number of them Irish, formed the majority of the population in many Northern industrial cities. Connolly argued in the Harp newspaper, "Immigration does not bring the Irish worker from slavery to freedom. It only lands him into a slavery swifter and more deadly in its effects."

The original Songs of Freedom includes "The Watchword," "When Labor Calls," "Hymn to Freedom," "Freedom's Pioneers," "A Love Song," "Human Freedom," "For Labor's Right" and "Freedom's Sun," all written by Connolly. "The Red Flag" by Jim Connell is also included. In "The Watchword," Connolly writes:

O, hear ye the watchword of Labor.

The slogan of they who'd be free,

That no more to any enslaver

Must Labor bend suppliant knee.

That we on whose shoulders are borne

The pomp and the pride of the great,

Whose toil they repaid with their scorn,

Should meet it at last with our hate.

In "A Rebel's Song," from 1903, Connolly writes:

Come workers sing a rebel song,

A song of love and hate,

Of love unto the lowly

And of hatred to the great.

The great who trod our fathers down,

Who steal our children's bread,

Whose hands of greed are stretched to rob

The living and the dead.

In "We Only Want the Earth," Connolly writes:

"Be moderate," the trimmers cry,

Who dread the tyrants' thunder.

"You ask too much and people By

From you aghast in wonder."

'Tis passing strange, for I declare

Such statements give me mirth,

For our demands most moderate are,

We only want the earth.Our masters all a godly crew,

Whose hearts throb for the poor,

Their sympathies assure us, too,

If our demands were fewer.

Most generous souls! But please observe,

What they enjoy from birth

Is all we ever had the nerve

To ask, that is, the earth.The "labor fakir" full of guile,

Base doctrine ever preaches,

And whilst he bleeds the rank and file

Tame moderation teaches.

Yet, in despite, we'll see the day

When, with sword in its girth,

Labor shall march in war array

To realize its own, the earth.

SONGS OF Freedom was first published in 1907 by J.E. Donnelly, the publisher of the Harp, the monthly organ of the Irish Socialist Federation founded by Connolly and other Irish socialists. The new Connolly songbook includes the 1919 James Connolly Birthday Celebration collection and also The James Connolly Songbook published by the Cork Workers Club in 1972.

In addition to the publication of the print collection, Mat Callahan, Yvonne Moore and others in the James Connolly Songs of Freedom Band have put music to the old revolutionary songs for a new generation of rebels. In his review of a live performance in Derry City, Eamonn McCann wrote:

One of the unexpectedly brilliant events of the year was the James Connolly Songs of Freedom Band at Sandino's in October, sponsored by Derry Trades Council. Not much of a turnout, it has to be said. We discovered many had assumed from its name that the band was of the fife-and-battered-drum variety.

It was anything but. The outfit offered blasts and orchestrations of sound, featuring guitars, fiddles, a whistle, an accordion, bodhran and uilleann pipes, with soaring vocals from Yvonne Moore and Geraldine Fitzgerald. They slammed into their set in a style reminiscent of Moving Hearts at the Baggot Inn.

Their specific accomplishment lies in giving Connolly's lyrics a rock beat while preserving a traditional skirl and keeping the socialist fervor. Songs to raise a scarlet banner to.

The publication of Songs of Freedom, both in print, through live performances and CD, are a useful contribution to recapturing and reconnecting with our revolutionary heritage. We need a revolutionary movement today and fierce revolutionary verse capable of articulating its spirit and hope.

In the field of poets, saints and sinners, Connolly probably is not in league with Oscar Wilde, W.B. Yeats, Samuel Beckett, James Joyce or Seamus Heaney, but whatever the shortcoming of his lyrical skills his disgust at inequality and injustice, his passion for working-class resistance and solidarity and his confidence in the possibility for a socialist future come shining through in these songs, as they do in his political writings.

For those interested in reading more about Connolly there are many studies available. Kieran Allen's The Politics of James Connolly is still the best available analysis of his ideas and actions; James Connolly and the United States: The Road to the 1916 Irish Rebellion by Carl Reeve and Ann Barton Reeve is an excellent study of his time in the U.S.; and, finally, the recently published 16 Lives James Connolly biography by Lorcan Collins is a very accessible, thorough and readable introduction to Connolly's life and contributions.