Queens scores a victory against gentrification

reports from New York City on a local battle pitting residents against the mega-developers who have their eyes on Western Queens.

RESIDENTS OF Astoria, Queens, scored a win against a proposed mega-development that would have taken over prime land overlooking Astoria Park and the Manhattan skyline.

After a packed-out special Zoning Committee meeting June 10, attended by over 300 people, with 56 people testifying, the committee recommended denying Alma Realty the go-ahead unless it met 47 conditions.

In response, Queens Community Board No. 1 unanimously voted June 17 to accept the Zoning Committee's recommendation, which many believe effectively kills the project. The final recommendations of the Zoning Committee were for requirements that 35 percent of final units would be affordable, that affordable units would be built in every phase of the 10-year project, and that residents of affordable units would not be segregated in one building, nor denied access to building amenities like rooftops or gyms.

People close to the process believe the city could add even more conditions in further in rounds of negotiation, making it impossible for this camel of rich developers to enter the kingdom of Astoria development.

The key issue that drew the most people and most resistance was affordable housing--both the guarantee that any new project would include a substantial portion of affordable units and outright rejection of any project that will ultimately raise rents in Western Queens.

According to Census data and the New York City Comptroller's Office, rents in Astoria went up between 30 and 39 percent between 2000 and 2012. The biggest increase in any New York neighborhood was the Williamsburg-Greenpoint area of Brooklyn, both formerly Polish and Puerto Rican enclaves that became the nesting ground for young artists and students pushed out of the East Village in the 1990s. Similarly targeted for rezoning and thoroughly transformed into a haven for wealthy hipsters, rents skyrocketed 70 to 79 percent in the same 12 years.

The closure of the Domino Sugar processing plant in Williamsburg and subsequent stalking of the site by developers led to one of the most contentious fights in Brooklyn--the developers' plan was ultimately accepted, but with 30 percent of units to be priced as affordable.

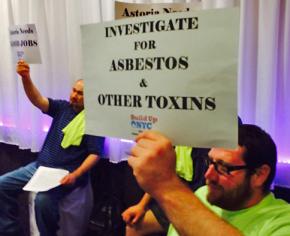

THE STANDING-room only crowd on June 10 represented multi-generation Astoria families; members of Occupy Astoria/Long Island City; union members from Build Up NYC; newer residents who themselves were pushed out of Manhattan and Brooklyn; and residents of Astoria Houses--the projects directly south of the proposed development.

The discussion opened with many of the 50-member Community Board raising criticism and questions, which encouraged others in the community to speak their mind.

Build Up NYC is a coalition of building trades and building services unions that have organized campaigns to force developers to contract for union workers during the build, and permanently as doormen and maintenance after completion. A series of union members spoke powerfully about safety training, wages and benefits that union jobs provide--including James, who had the misfortune of working in a building bought by Alma, which then cut wages by 50 percent.

While it would undoubtedly be better to have union jobs than not, the question that needs to be asked urgently is why the only jobs available will be in these playgrounds for the rich. Some of the union speakers were Astoria or Queens residents, who spoke about rising rents and the impossibility of buying a home in the area.

Community Board members and residents also focused on the effect of increasing population on the area's stressed infrastructure. Another mega-project, Hallets Cove development, which will have 2,500 units, has already been approved.

While developers proposed private shuttles to train stations, there is no talk of increasing trains or buses to the area. In fact, Astoria lost two train lines in the recent past: the W, which ran parallel to the East River near the proposed development; and the G, which ran further inland and straight to Brooklyn. Community activists have been pushing for a ferry service to Manhattan, but there is no commitment from the city as of yet.

Plus, contrary to all common sense, the entire project is in a Zone A evacuation area--meaning it is low-lying ground and will be the first to be hit by rising waters during another Superstorm, like Sandy in October 2012. Just blocks away, Astoria Houses did experience flooding and loss of power in some buildings during Sandy.

While winning the conditions and possibly blocking this project is an important victory, the gentrification war in Western Queens is far from over. Projects are in the works for a corridor from the western-most Long Island City--already home to over a dozen luxury towers and complexes--all the way along the 7 train to CitiField in north-central Queens.

During the final lame-duck period of Mayor Michael Bloomberg's reign, the city gave away 40 acres of parkland (currently used as parking for CitiField) to a complex of malls and hotels. A proposed Business Improvement District in Jackson Heights-Corona is a Trojan horse for rezoning and replacing locally owned shops that serve and employ the neighborhood immigrant population.

Central to the success of these projects getting residents on board is the refrain "this is the only way to get jobs/funding/resources for our neighborhood to fix X problem." Yet often the "X problem" is the result of poverty or neglect by city agencies, which are often underfunded or pressured to find private sources of funding. Astoria is in the most over-crowded school district in the city, yet school building has only been promised in the shadow of Hallets Cove, and now Astoria Cove.

Activists confronting real estate vultures can defend our neighborhoods--but we need to set our sights even higher to reverse the trend of organizing public resources for the private market, and hoping some crumbs will fall onto our plates.