Confronting the epidemic of police murders

The movement against police abuse needs to not only hold the cops responsible for their crimes, but imagine a real alternative to state violence and repression.

IS THERE any doubt that the police are out of control?

If the deaths of Mike Brown in Ferguson, Missouri; Eric Garner in New York City; John Crawford in Beavercreek, Ohio; Tony Robinson in Madison, Wisconsin; and so many others didn't drive home the reality, now there is video of officer Michael Slager firing eight times into the back of a fleeing Walter Scott in North Charleston, South Carolina, and of reserve sheriff's deputy Robert Bates shooting a prostrate Eric Harris at point-blank range in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

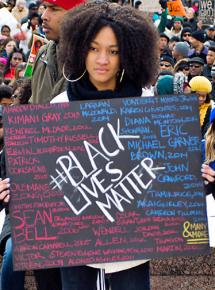

These cases have become the predictable norm on the evening news--not because there weren't equally barbaric police murders in the past, but because the Black Lives Matter movement has succeeded in piercing the bubble of public consciousness about the scale of brutality and racism that the African American community faces on any given day at the hands of law enforcement.

Starting last summer after Mike Brown's killing, the calls for reform--such as mandatory body cameras on police and independent civilian reviews boards--have grown. These measures are important for the movement to take up, but it's critical that the larger questions about the role of police not go unanswered--above all, that the police as an institution don't exist to "serve and protect," but to uphold a racist justice system and protect private property.

That's why, as important as the outpourings of anger and grief on the streets are, it's a welcome sign that activists--such as the Young, Gifted and Black Coalition in Madison, Wisconsin--seek to build sustained movements taking on not just individual cases of police violence, but the larger edifice that produces it.

A new generation is fighting not only to hold individual police officers responsible for their violence, but to indict an entire system built around brutality and racism.

THE DEATH of Walter Scott was an execution, plain and simple.

The video showing an unarmed Scott running from Michael Slager, and Slager firing multiple shots at Scott's back--and then, after Scott falls, dropping a Taser at the dying man's side--is shocking not only for the murderous violence it shows, but for Slager's almost nonchalant demeanor as he, without hesitation, frames his victim.

Slager, after a public outcry, was arrested and charged with first-degree murder. The media that at first blindly supported his claim that Scott "attacked" him and grabbed for his gun were forced to backtrack once cell phone video taken by a bystander showed the truth. Until then, Scott's previous arrests and his alleged failure to make child support payments were used as retroactive justification--if not for his death, then at least to prove he could have been the "type" of person to struggle with a cop over his gun.

As horrifying as Michael Slager's actions were, he isn't simply one "bad apple." He's part of a whole rotten barrel.

The narrative of the heroic cop "forced" to fire is time-tested. Usually, of course, there isn't cell phone video to show what really happened, and the word of the police is taken as gospel truth, even when there's evidence to contradict them. Only when the evidence is overwhelming--like the video of Slager gunning down Walter Scott--is that narrative questioned. Otherwise, it's rare when police face the same assumptions made about their victims.

Take the case of reserve sheriff's deputy Robert Bates, who killed Eric Harris earlier this month in Tulsa, Oklahoma. While Harris was routinely described as a "convicted felon" and worse, few people questioned the mindset of the cop who "accidentally" killed him.

"Deputy" Bates, in fact, is a "wannabe cop"--a millionaire insurance salesman who made substantial financial contributions to the department for vehicles and other equipment (including, ironically, the Google Glass that recorded him killing Harris). In return, he could moonlight in Tulsa's Reserve Deputy Program.

According to the New York Times, Bates isn't unique: "He is among scores of civilian police enthusiasts, including wealthy donors to law enforcement, who effectively act as an armed adjunct to the Tulsa County sheriff's office."

Bates wasn't assigned to the Violent Crimes Task Force arrest team that targeted Harris except in a "support role." His duties were supposed to include things like "keeping notes, doing counter-surveillance," according to Major Shannon Clark. Instead, Bates jumped into the confrontation between a large group of officers and Harris, and fired a gun into Harris' back.

Bates claimed he mistakenly pulled a gun instead of a Taser. Even if that's true, it wasn't a mistake when Bates' fellow officers, rather than try to help Harris, pinned him to the ground--with one officer placing a knee on the bleeding man's head and yelling at him to "shut the fuck up" as he struggled for breath. When Harris exclaimed, "I'm losing my breath!" an officer responded, "Fuck your breath."

Tulsa police initially told the media that an "investigation" by the Tulsa County Sheriff's Office concluded that Bates didn't commit a crime and no policy violations occurred. According to Andre Harris, Eric Harris' brother, a deputy from the sheriff's office advised him not to get a lawyer and lied about his brother being under the influence of drugs, according to Business Insider. "If you hire a lawyer, it will gum things up," an officer allegedly told Andre.

AS THE whole country is finally beginning to understand, Walter Scott and Eric Harris are only the latest victims of police. According to the website KilledByPolice.net, which tracks media reports of police killings in the U.S, 332 people had been killed by the police in the U.S. already this year, as of April 15.

Can there be any excuse for this epidemic of police murder? As New York Times columnist Charles Blow pointed out, those looking to blame brutality victims for such "crimes" as running from police or having an outstanding warrant are engaging in the worst sort of victim-blaming:

It is tragic to somehow try to falsely equate what appear to be bad decisions made by Scott and those made by the officer who killed him. There is no moral equivalency between running and killing, and anyone who argues this obdurate absurdity reveals a deficiency in their own humanity. Death is not the appropriate punishment for disobedience. Being entrusted with power does not shield imprudent use of power.

Despite the video evidence of their killings, however, neither Michael Slager nor Robert Bates are likely to see a day in jail.

That's because the odds are so overwhelmingly stacked in favor of the police that even documented cases of brutality and murder are deemed to not meet the legal standard of a crime. A recent investigation by the Washington Post and researchers at Bowling Green State University found, "Among the thousands of fatal shootings at the hands of police since 2005, only 54 officers have been charged...Most were cleared or acquitted in the cases that have been resolved."

In most cases, the report found, officers were charged only if the person they killed was unarmed--but even that typically wasn't enough. Usually a case also had to include other factors for prosecution like a victim being shot in the back or incriminating testimony from other officers.

On the very rare occasions when police are convicted, "they've tended to get little time behind bars, on average four years and sometimes only weeks," according to the Post. Indeed, the crime Robert Bates is charged with--second-degree manslaughter--carries a maximum jail sentence of just four years. And the maximum is unlikely to be doled out to an "upstanding" officer who "accidentally" caused the death of a "criminal."

THE APPARENTLY escalating epidemic of police violence--and the total lack of accountability for cops--has prompted calls for various reforms, from mandating that police wear body cameras to calls for civilian review boards to handle allegations of misconduct and violence made against cops.

It would be a step forward if reforms could be put in place that would make it easier--or merely possible--to hold police accountable. One obvious measure: The bloated police budgets spent on crowd-control weapons and military surplus should be drastically cut, and the money used to benefit communities. Victims of police violence should be well compensated, and cops who are found to have engaged in brutality should lose their jobs and face prosecution.

But some of the most talked-about reforms have serious limitations. In the case of body cameras, for example, there is evidence that they can have some impact on police behavior. A 2012 study of police in Rialto, California, for example, found that use-of-force complaints were lower when officers were equipped with cameras--cops not equipped with cameras were more than twice as likely to use force as those who had them.

But there are ways around body cameras. The limitations are apparent when you consider the case of Eric Garner, whose killing by an NYPD officer using an illegal chokehold was caught on video, but still didn't bring an indictment. (Meanwhile, Ramsey Orta, who recorded the video of Garner's death, was behind bars for two months until last week as a result of a trumped-up drug charge, in what many believe was retaliation for releasing the video of Garner's death.)

During a six-month-long trial of body cameras in the Denver Police Department, only a quarter of incidents where officers used force were actually recorded. According to an independent monitor, "Cases where officers punched people, used pepper spray or Tasers, or struck people with batons were not recorded because officers failed to turn on cameras, technical malfunctions occurred, or because the cameras were not distributed to enough people," the Denver Post noted last month.

Meanwhile, the push to equip officers with "less lethal" options like Tasers hasn't stopped police killings, but merely given officers another weapon in their arsenal with which to threaten and brutalize people. In South Carolina, the jurisdiction where Walter Scott was killed has been referred to as "Taser town" as a result of the police propensity for Tasering suspects--on average, once every 40 hours during one six-month stretch.

In February, in Fairfax County, Virginia, Natasha McKenna, a mentally ill woman, was killed by police who used a stun gun on her, despite the fact that her hands were handcuffed behind her back and her legs shackled. The 130-pound woman had been "subdued" by six officers, but when she refused to bend her legs for placement into a restraint chair, they administered four 50,000-volt shocks, sending her into cardiac arrest.

Calls for civilian review boards are also problematic. Theoretically, an independent review board with real power and oversight might be able to punish police abuse. But in practice, the power of police unions, tough-on-crime and pro-cop politicians, and a host of other factors mean that civilian review boards, where they do exist, are hamstrung at best in doing anything except ineffectual protests of police actions and recommendations for departmental change that are typically ignored.

THIS DOESN'T mean that activists should dismiss measures intended to rein in police and hold them accountable--they can have real consequences. But at the same time, we have to point out that even if reforms can be made effective, they won't alter the nature of the police--which is to act as a special body of armed men in service of the state and private property.

Racism is built into the nature of policing in the U.S., because it is built into the fabric of U.S. society as a whole and the U.S. criminal injustice system in particular. This is why systemic police brutality exists, not because of individual bad and violent cops.

Writing in Britain's Guardian newspaper, Steven Thrasher pointed out that for many communities, there is a world of difference between policing and helping people to feel "safe":

The footage of [Eric Harris'] murder was captured by the type of camera of which President Obama wants 50,000 more. To what end? To better document the pornography of our genocide? To allow Tulsa officials to say with impunity that the next Bob Bates (the 73-year old pay-to-play volunteer cop who shot Harris) also meant to use a Taser and not a gun? To write that off, too, as "a mistake," with no further plans for investigation?...

This weekend, Black Lives Matter activist Cherrell Brown asked audience members of a conference on policing that I attended to close our eyes and imagine a place where we felt safe. No one imagined a place with cops, cameras, guns, or attack dogs. And yet, as Brown noted, we're asked to believe that, to feel safe, we need more cops in New York City, more racially diverse cops, more cops wearing cameras--more law enforcement, not more safety.

The U.S. today incarcerates more of its population than any other country on the planet, largely for crimes related to poverty. Real "safety" for the majority doesn't come from the police, because the very nature of the police is to guarantee safety and security for those who rule society.

To make communities truly "safe" would require fewer cops--but more living-wage jobs, health care for all, decent housing and fully funded schools. In Madison, activists in the Young, Gifted and Black coalition have made a point of calling for the release of prisoners incarcerated for crimes of poverty and opposing public funding to build or rehab jails. Their actions have put Madison Police Chief Mike Koval on the defensive and forced him to acknowledge "the racial disparities issues that have been well-substantiated for our city."

It's up to us to continue building a movement that can both attempt to hold police accountable and to imagine a real alternative. We deserve nothing less.