The sun, the rain and the whip

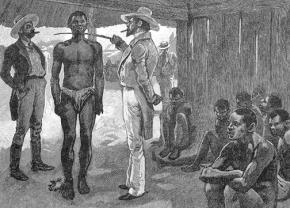

A new book by Edward Baptist's book shows that the "peculiar institution" of slavery made future U.S. economic dominance possible, explains .

"Changes that reshaped the entire world began on the auction block where enslaved migrants stood, or in the frontier cotton fields where they toiled...Enslaved African Americans built the modern United States, and indeed the entire modern world, in ways both obvious and hidden."

-- Edward Baptist, The Half Has Never Been Told

THIS VITAL and enthralling book reveals how U.S. capitalism was built on the torture of enslaved people. Edward Baptist quotes a Mississippi overseer telling his friends that "the whip was as important to making cotton grow as sunshine and rain." The whip "might open deep gashes in the skin of its victim, make them 'tremble' or 'dance'...but it did not disable them."

Women who didn't pick cotton fast enough were forced "to kneel in front of their baskets," Baptist writes. "Shoving their heads in the basket, [the overseer] would pull up their dresses and beat them until the blood ran down their backs."

Torture wasn't an aberration--it was the basic means of extracting ever more production from enslaved people. One man named John Brown recalled that "as I picked so well at first, more was required of me, and if I flagged for a minute, the whip was applied liberally to keep me up to my mark. By being driven in this way, at last I was able to pick a hundred and sixty pounds a day" after starting at a minimum requirement of 100 pounds.

Enslaved people were given a quota to pick. Anyone who didn't make their quota was whipped. As soon as they made the new quota, a new higher one was required, again on pain of the whip.

This torture compelled enslaved people to constantly innovate in the desperate drive to produce ever more cotton. Baptist writes that this "repeatedly accomplished the enslaver's ongoing goal of forcing enslaved people to invent, over and over again, ways to make their own labor more efficient and profitable for their owners."

The cotton extracted by this forced labor fueled the growth of U.S. capitalism. The first modern factories were textile mills to turn cotton into cloth that could make clothing. Northern financiers invested directly in slavery. They bought from and sold to slave owners. Bankers and investors even bought bonds secured by the title deeds to enslaved people whose labor was now a commodity. As Baptist writes:

Cotton became the dominant driver of U.S. economic growth. In 1802, cotton already accounted for 14 percent of all the value of U.S. exports, but by 1830, it accounted for 42 percent--in an economy reliant on exports to acquire the goods and credit it needed for growth.

Baptist, however, believes that "all northern whites had benefited from the deepened exploitation of enslaved people." It's true that the profits from slavery made jobs in the new textile mills possible. But the women and children working in those mills 12 hours a day, six days a week, for starvation wages, were hardly benefiting from the new industrial order built on enslaved people's labor.

SLAVERY HAD its own contradictions that eventually proved fatal. Like capitalism, it had to continually expand. King Cotton exhausted the soil wherever it went. The huge profits slave owners demanded largely precluded crop rotation or allowing fields to lie fallow.

By 1820, slave masters in the Old South of the Carolinas, Virginia and Maryland were selling enslaved people to work in the cotton fields of the Lower South. These sales enabled them to raise large sums of money quickly to offset their dwindling income. In The Political Economy of Slavery, Eugene Genovese writes:

The sale of surplus slaves depended on markets further south, which necessarily depended on virgin lands in which to apply the old, wasteful methods of farming...The steady acquisition of new land could alone guarantee the maintenance of that interregional slave trade which held the system together.

The Half Has Never Been Told describes the human cost of slavery's extension to the south and west. "Hurrying in lockstep, the 30-odd men came down the road like a giant machine," writes Baptist. "Each hauled 20 pounds of iron, chains that draped from neck to neck and wrist to wrist, binding them all together." In the words of Baptist:

Expansion was marked by vast suffering. In it, hundreds of thousands of people died early and alone, separated from their loved ones. Millions of people were lost by millions of people. By the water's edge they parted."

Enslavers had to control the federal government to ensure that slavery could continue to expand into new territories. Slavery was written into the U.S. Constitution, with every slave counting for three-fifths of a free man toward a state's delegation in the House of Representatives.

In the decades leading up to the Civil War, slavery's expansion haunted American political life. One "compromise" after another--from the Wilmot Proviso to the Missouri Compromise, the Kansas-Nebraska Act and the Compromise of 1850--appeared to resolve it, while perpetuating slavery's steady expansion. But each time, the debate resumed in a more intense and bitter way.

UNTIL ABRAHAM Lincoln was elected in 1860 on a platform of ending slavery's expansion, the South controlled the White House. Five of America's first seven presidents owned slaves. They were succeeded by "Northern men of Southern principles," pledged to support the expansion of slavery.

Enslavers chose secession and war rather than remain in a country whose president was resolutely opposed to slavery's expansion. They started something which finally led to the end of U.S. slavery.

Baptist demonstrates that it was slavery's expansion, not the existence of slavery itself, which precipitated the Civil War. But once the war began, slavery was doomed. Enslaved African Americans forced the issue by fleeing en masse to Union lines, later enlisting to fight for their own liberation.

The Half Has Never Been Told belongs on every socialist's bookshelf. It deserves to be read, re-read, pondered and debated. It is especially essential because Baptist tells the story very largely from the point of view of enslaved people, relying heavily on interviews done for the Works Progress Administration in the 1930s:

-- Frances Frederick told of the morning he started his forced march from Virginia to Kentucky. He saw men and women "on their knees, begging to go with their wives or husbands." He recalled that the begging was "of no avail."

Something died in Lucy Thompson when she was sold from Kentucky to New Orleans and separated from her mother. "Years later, she remembered her zombie days. And she never forgot the men who called to her...Liza, they sang. Lucy raised her head. Tears flowed down her face, and she opened her mouth. 'I got happy,' Lucy Thompson remembered 80 years after her resurrection 'and sang with the rest.'"

Charles Ball had left his family behind in Maryland when he was sold to South Carolina where "he adopted a trade-orphaned little boy 'the same age [as] my own little son whom I had left in Maryland; and there was nothing I possessed in the world I would not have divided with him, even to my last crust.'"

The slavery they endured is gone, but U.S. capitalism's super-exploitation of Black labor has never ended. In 2011, with Barack Obama in the White House, white households made $27,415 more a year than African American households.

The Half Has Never Been Told is a clarion call for the full emancipation of African Americans. Yet it also demonstrates that it will take the final abolition of U.S. capitalism, which began oppressing Black people in 1619, when the first slaves arrived in Virginia, and continues today, to achieve that aim.