The watcher and the watched

reviews an art exhibition by filmmaker Laura Poitras that takes a deeper look at the National Security Agency's surveillance state.

THE IDEA of being spied on by an individual--be it an ex-lover, creepy neighbor or complete stranger--is deeply disturbing. And yet most of us go about our lives in full awareness that we are constantly being tracked by more impersonal forces, from the cameras that now seem to be on every street corner to the websites we use every day.

Thanks to the heroic whistle-blowing of Edward Snowden about the massive surveillance of phone and Internet communication conducted by the National Security Agency (NSA)--all in the name of supposedly keeping us safe by finding the bad guys among us and taking them out--we now have a much more specific understanding of how and by whom we are being watched.

But for many, that knowledge has only reaffirmed the passive fatalism that there is no such thing as privacy in the 21st century.

Laura Poitras is the filmmaker who helped Snowden tell his story in the documentary CITIZENFOUR. From the day she was first contacted by Snowden, Poitras felt that the full impact of his story couldn't only be conveyed by the narratives of journalism and documentaries, but also had to connect with our emotions in the way that only visual art can.

In her journal, she wrote about "the power of images to tell the news in ways that have to be confronted emotionally." Excerpts from that journal are published in Astro Noise: A Survival Guide to Living Under Total Surveillance, the catalog for Astro Noise, Poitras' exhibition at the Whitney Museum in New York City.

Astro Noise is an ambitious attempt to put visitors in the roles of watcher and watched in an array of locations throughout the global surveillance apparatus in the U.S. and the Middle East. The title of the exhibition comes from the name of the encrypted file containing evidence of NSA spying that Snowden gave to Poitras in 2013.

Snowden apparently has a dark sense of humor. According to the catalog, "astro noise" originally referred to "the faint background disturbance of thermal radiation left over after the big bang" that astronomers originally thought was a technical error--a creepy analogy to a Truman Show scenario of people catching glimpses of the hidden cameras that surround them and concluding that it's just their own paranoia.

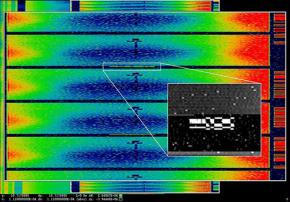

AT THE entrance to Astro Noise, visitors first see Anarchist, a series of images taken from the British and U.S. surveillance program of that name (perhaps because they follow no laws?).

We are looking at human activity and communications that have been turned into data and then presented in colorful graphs and lines, which in a museum setting becomes art. It's one of many ways that Astro Noise explores the relationship between surveillance and art.

Other installations are far less abstract. O Say Can you See takes visitors back to the events around September 11, 2001, that marked a turning point in the escalation of the surveillance state. The installation is a double-sided movie screen: one side presents slow motion images of people's faces as they react to the (off-camera) destruction of the World Trade Center--the other shows footage of chained and hooded men being interrogated in Afghanistan in the ensuing months.

November 20, 2004, takes visitors to the day that set Poitras on a path toward CITIZENFOUR and Astro Noise. That's the day she landed on the government's secret watchlist when, as an "unembedded" journalist in Iraq, she took video of a family reacting on their rooftop to a nearby firefight with American soldiers. The installation is an audio recording of Poitras explaining the events of that day and their aftermath, alongside the unedited video from the rooftop and the FBI document putting her on the watchlist that she filed a Freedom of Information Act to obtain.

Other installations are subtler, and rely on visitors to decide, in the words of the exhibition, "how deeply to look" and "how to interact with others in the same space confronted with these same questions."

Disposition Matrix is series of images behind narrow lit slits in an otherwise dark hallway. Visitors peer into the slits like peeping Toms, seeing everything from classified NSA documents to videos of inmates at Guantánamo Bay to surveillance-style video taken outside NSA headquarters itself.

Similarly, Bed Down Location is a room in which visitors can lie down and look at a projected image of a night sky at various locations in the Middle East. When I was there, some attendees briefly lay down, felt like they got it and moved on, while others stayed for a while and seemed to embrace the idea of imagining trying to sleep in an area known for drone bombing attacks.

Further on in the exhibition is a screen showing infrared images of the people lying down in Bed Down Location, putting visitors in the role of drone operators--and spies on their fellow museum attendees.

POITRAS IS clearly concerned about the ways that the surveillance state implicates all of its citizens, and the artist in particular--the infrared screen is located near the screen showing her video from November 20, 2004.

Documentary filmmakers, like spies, make decisions about how to frame the motivations of the people they are recording. As Poitras writes in her journal:

When I make films, I witness and record moments of uncertainty that unfold in real time. The future is unknown, often full of risk for the people I document. When I edit those moments months or years later, the future has transpired and the uncertainty is transformed into a plot: a narrative in which decisions that were vast and multiple are reduced to one--the path taken, not the many paths untaken. But the drama, the life pulse of any story, lies in the uncertainty of the moment, the choices, doubts, fears, desires and risks of how to act and act again.

But what Poitras' exhibition makes clear is that art is interested in finding what is human out of impersonal systems, while the project of the security state is precisely the opposite. Astro Noise is not just about surveillance but Big Data--how governments (and corporations) track our communications, desires and relationships in order to round them off into simplified and predictable patterns and pathways.

What Snowden has revealed is that for the most part, government spies are less interested in what we have to say than who we talk to. The government never even asked to view the video that got Poitras on its watchlist.

That makes the mundane rooftop footage of that Iraqi family--along with the other installations in Astro Noise--seem very important. It's hard to leave the exhibition without making a vow to try to keep finding ways to resist the ubiquitous surveillance that can sometimes seem as untouchable as the faint noise coming from distant ends of the universe.