A new generation’s Pine Ridge

The spreading movement in solidarity with the resistance in Standing Rock recently landed in Rochester, New York, report and .

NEARLY 40 people packed into a room at the Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT) on October 27 to hear a panel discussion on "Solidarity with Standing Rock."

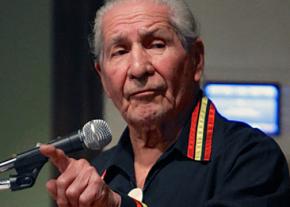

Speaking were two notable figures from Native American communities in upstate New York: Chief Oren Lyons of the Onondaga Nation and Peter Jemison of the Seneca Nation and the Ganondagon Arts and Cultural Center. Socialist Worker contributors Sara Rougeau and Brian Ward also joined the panel via Skype to report on their recent trip to the protest encampment at the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation in North Dakota.

The immediate goals of the meeting were to express solidarity with the efforts of water protectors who are putting their bodies on the line to halt construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) and to spur further organizing on RIT's campus. The speeches and discussion focused on the history of Native American resistance to U.S. genocide and occupation, the goals and actions of the environmental movement, and what socialists can offer the movement.

Chief Lyons, who has been a leading advocate for Indigenous sovereignty since the 1960s, stressed the importance of educating people about the real history of this country (now called the United States). He is a traditional Faithkeeper of the Turtle Clan and a tenured professor of American Studies at the State University of New York at Buffalo.

"When Columbus landed, there were 16 million people here," said Chief Lyons. "By 1900 there were only 250,000 left." He eloquently contrasted this history of oppression with the rich history of Native resistance--from the Battle of Little Big Horn to the occupation of Wounded Knee in 1973.

He also focused on the need to shred myths about Native Americans, typified by the stereotypical "Indian" portrayed in Hollywood movies. As Chief Lyons put it, "The Nina, Pinta and Santa Maria did not bring democracy to this land. It was already here, and we were free...The guiding principle of Indigenous life prior to the arrival of the Europeans was community, and the first law of our people was to share. This is contrary to capitalist thinking, you're taught not to share."

As Native people have fought back against the destructive impacts of capitalism, "Indigenous people of this land have been called communists, and we have been called socialists," Chief Lyons recalled.

The final point that Chief Lyons conveyed was the historical importance of leadership within Native American culture and the need to train future leaders. Because of the increasing intensity of the destruction on the planet, he spoke with an air of caution, but was optimistic about the possibilities of his granddaughter's generation--of young people today.

Jemison spoke briefly but urgently about the need to protect rights guaranteed, but largely abrogated, in the treaties signed by the U.S. government. Both the Onondaga and Seneca peoples belong to the Haudenosaunee ("People of the Longhouse"), also known as the Six Nations of the Iroquois confederacy, the inhabitants of Western New York prior to conquest and colonization by the Europeans.

The treaties signed by their forbears mark the very first agreements reached between the newly independent United States and the existing Native peoples, whose lands were progressively taken away. The oldest treaty of Canandaigua, dating from 1794 and signed by George Washington, is due to be renewed in a ceremony on November 11.

THE IMPORTANCE of using treaties to support and defend Native resistance was highlighted throughout the speeches. This is even more significant in the wake of the recent repression and attacks against the "Treaty Camp" constructed directly in the path of the Dakota Access Pipeline.

The camp takes its name from the Treaty of Fort Laramie in 1968, which gave all lands in South Dakota west of Missouri River to the Sioux Nation. While the treaty was broken only 11 years later, as the U.S. forcefully stole lands in the Black Hills when gold was discovered, it and other treaties have been used numerous times to support the struggles of Native activists and cited in court to defend the actions of protesters, as is once again the case at Standing Rock.

Ward and Rougeau described how the current movement has brought together Indigenous activists along with growing numbers of non-Native supporters in the largest mobilization for Native rights since the Pine Ridge and Wounded Knee occupations in the 1970s. Indigenous people in Standing Rock are demonstrating what others need to do to fight back against our common enemy--namely, the economic system that puts profits over people and the earth.

The discussion began with a question from the president of the Native American Students Association. She asked, "As socialists, what do you think the next step should be here on campus?"

This question led directly into a conversation about what we can do to raise awareness and challenge the system wherever we are. Plans are now underway organize an even bigger student rally on RIT's campus in order to raise funds and build solidarity in support of the efforts at Standing Rock.

Capitalism is forcing many young people to question the evils it produces every day, and struggles like Standing Rock are the key to building a fighting force that can stand up to the power of the corporations and government.