Why did Turkey’s regime turn to the iron fist?

To understand the sources of state repression and violence being inflicted in Turkey, looks at the history of the ruling party and the deepening crisis it faces.

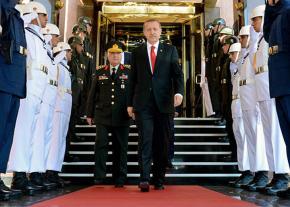

"A GIFT from God." That's what Turkey's President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan said of the failed coup against his government last July.

It was signal that the aftermath of the botched takeover would be used as an opportunity to purge former allies-turned-enemies who are accused of plotting the coup. But it quickly became clear, as Erdoğan's Justice and Development Party (AKP) declared a state of emergency, that he has his sights set on a much broader range of opponents.

The uprising that aimed to topple the government last July was concentrated in a section of the military among followers of cleric Fetuhallah Gülen, the leader of the Hizmet movement. The Gülenists--who advocate a different interpretation of Islam to the AKP, but are similarly pro-business and socially conservative--were early allies of Erdoğan's party when it first came to power in 2002, but tensions grew to the breaking point, especially during the last several years.

But Erdoğan's counter-coup has gone much further then the Gülenists. Leaders of the left-wing People's Democratic Party (HDP), including its representatives in parliament, have been arrested and held, even though the HDP immediately and vocally opposed the coup.

The oppressed Kurdish minority that accounts for the HDP's main base of support has been especially hard hit. Dozens of mayors in Kurdish towns have been removed from their positions. The Middle Eastern news website Al-Monitor reported last month that an estimated 32,000 Kurds in the war-torn and impoverished Southeast of the country were without food support after a charity, the Samarsik Organization, was closed and its board of directors arrested.

The government's operations are also directed at sections of the country's power structure. More than 125,000 state employees have been dismissed or suspended due to alleged links to the Gülenists or the rebel Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK). Almost 28,000 teachers had been suspended as of last September. Judges, police and other public officials have been detained, arrested, dismissed or suspended.

The repression has also hit the media. Reporters and executives of the opposition newspaper Cumhuriyet were arrested for having alleged terrorist links, and are among a growing group of journalists behind bars.

ERDOGAN HASN'T simply used the Gülenists as a pretext for repression. He is determined to wipe them out.

Hundreds of supposed Gülenist businesses have been seized by the state, while prominent businesspeople with links to the Gülen network have been arrested. Gülenist educational institutions--from religious instruction and standardized test tutoring to universities--have been shut down or taken under state control. And Turkey has been pushing the Obama administration to extradite Fethullah Gülen, who lives in self-imposed exile in the U.S.

Amid this repression, Erdoğan is quickly moving forward with his long-held aspiration to strengthen his position as president by re-writing the constitution. The AKP has formed an alliance with the far-right Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) to try to push through a constitutional revision that would give the office of president increased powers over the judiciary and government ministries, and the ability to declare states of emergency and unilateral presidential decrees, and even dissolve parliament.

Meanwhile, the Turkish military is embroiled in conflicts in Syria and Iraq, not to mention counterinsurgency operations within Turkey, and the AKP is driving regional instability to new heights with its growing collaboration with Russia, the chief imperial ally of Bashar al-Assad's dictatorship in Syria. The recent assassination of a Russian ambassador in Ankara is one example of blowback from these interventions.

Economically, the national currency, the lira, has been losing strength relative to the dollar, and there is a free fall in foreign direct investment, an essential component for Turkish economic growth. While Erdoğan blames shadowy conspiracies for his economic woes, economists and financial groups around the world aren't convinced.

Though the atmosphere of crisis has escalated massively, the AKP's drive to repression and war is the culmination of conflicts and contradictions that began to unfold after the Great Recession of 2007-08. Understanding what is taking place in Turkey today--including the rupture of the alliance between the AKP and the Gülenist network--requires understanding the backdrop to the AKP's rise to power.

THE AKP is the descendant of a long line of Islamist parties that represented the interests of the rising Anatolian bourgeoisie whose economic power was based in manufacturing in eastern Turkey. Allied with conservative middle-class Muslim Turks, they backed a series of Islamic parties led by Necmettin Erbakan, beginning with the National Order Party.

Islamism emerged and grew in influence in the 1960s and 1970s. Working-class militancy was also on the rise as industry developed in the major cities of Turkey. Even after coups in 1960 and 1971, unrest continued, breaking out into violent struggles between revolutionary left and fascist organizations.

This culminated in the most extreme of Turkey's coups--in 1980, when hundreds of thousands of people were arrested, with many tortured in prisons and disappeared, and dozens officially executed. The repression was largely directed at the working-class movement, while the fascists were let off lightly, when they were targeted at all.

The coup regime, as a representative of the powerful capitalists of western Turkey, sought to restructure the economy along neoliberal lines. In order to integrate Turkey into the global economy, state-owned enterprises were slated for privatization, and industry was retooled for export instead of domestic consumption. The regime and its elite backers also looked to membership in the European Union to further the process of economic integration.

Erbakan's National Order Party was banned in 1980, along with all the other official parties. However, despite a long-time commitment to secularism, the Turkish military promoted what it deemed to be moderate Islamism as an alternative to revolutionary politics.

When party politics were legalized again in 1983, Islamism organized as the Welfare Party (WP). Under Erbakan, the WP would go on to win significant electoral victories from 1991 to 1996, becoming the largest party in parliament. Erbakan himself became leader of parliament. But in 1997, the military again intervened, this time explicitly against the growing influence of Islamist politics, and Erbakan was forced to step down.

The ruling class of Turkey was faced with a political problem. Despite its commitment to neoliberalization--expressed through the main manufacturing organization TÜSIAD--it hadn't found a party that could build sufficient consent around the restructuring. After another military intervention into politics in 1997, none of the establishment parties seemed capable of mobilizing enough public support for these programs.

In 2001, the AKP formed as a splinter from the new Erbakan-led party, now called the Virtue Party. Led by Erdoğan and backed by MÜSIAD, the manufacturing association of the Anatolian bourgeois, the AKP won a major victory at the polls in 2002. Erdoğan became prime minister.

The AKP renounced the explicit Islamism of Erbakan and moved away from transnational Islamism and the Virtue Party's social justice language. While maintaining an image of popular support through the creation of social welfare program, the AKP committed itself to neoliberalism--and formed an alliance with the Gülenist network to carry out its program.

GÜLENISM EMERGED in the late 1960s along with other Islamist currents as a Sufi organization led by the charismatic Fethullah Gülen. He and his supporters renounced the project of building an Islamic state as well as transnational Islamist politics.

Gülen promoted a balance of science and religion, as well as Turkish nationalism and integration into the market economy. The Gülen network formed its own business association, TUSKON, and an extensive system of schools to teach for the mandatory Turkish examinations. At their height, these schools taught more than 1 million students in Turkey and expanded their operations to dozens of other countries.

The Gülenists operated an extensive charity network that provided essential services at a time when social spending was being slashed. The Gülenists controlled important media outlets that were essential to both glorifying the AKP after its rise to power and criticizing the secularist state and the Turkish military, not to mention other opponents. Gülen had encouraged his followers to try to get important state positions even before the alliance with the AKP.

MÜSIAD and TUSKON greatly benefited from the post-1980 coup environment. Committed to the neoliberal project, their businesses expanded greatly under the reorientation toward an export-based economy. They shared conservative Islamist ideologies, as opposed to the secularism promoted by the military and the western Turkish business class. The Islamist currents likewise shared a common enemy in the military, which in both 1980 and 1997 threatened their political objectives.

DESPITE THE misgivings of the capitalist class concentrated in Western Turkey, the AKP presented itself as a political party able to maintain mass support while carrying through neoliberal restructuring.

With the support of the vast resources of the Gülen network, the AKP built a strong base among the poor through social welfare measures. State spending on welfare grew from 1.4 billion lira in 2001 to 24 billion in 2013. These projects were buoyed by informal Islamist charity work that provided basic necessities and job opportunities, further building grassroots support.

Backed by both TÜSIAD and MÜSIAD, Erdoğan privatized state enterprises, restructured the banking sector and moved the lira into a floating exchange system. This contributed to strong economic growth between 2002 and 2007, with the annual increase in gross domestic product running at 7.2 percent per year during the period. Even after the Great Recession struck, Turkey's economy rallied in 2010 and 2011.

Many of the neoliberal "reforms" were dependent on the historical weakness of Turkish trade unions. While the poor gained economic support from the welfare programs and the Turkish population experienced increased spending power in general, formal trade unions were under attack. In 2003, a labor reform law was passed to promote "flexible" labor policies, and further legislation has been put on the table to increase temporary employment, further undermining unionization.

The AKP also won support from the liberal intelligentsia. The party promised to work toward Turkey's entrance into the EU, which would require not only economic but political reforms. The AKP positioned itself as the party of democracy, against the coup-making military and the big Western-oriented businesses that didn't care about ordinary people.

In 2007, the military colluded with the center-left Republican People's Party (CHP)--for decades, the dominant political party before the rise of the AKP--and the far-right MHP in an attempt to push the AKP out of power. This time, the attempt failed. Under attack from the traditional forces of repression, Erdoğan and his party were able to mobilize a counterattack.

Supported by the Gülenists' substantial media resources, the AKP exposed two alleged military plots: ERGENEKON in 2008 and Sledgehammer in 2011.

Hundreds of military personnel were convicted and sentenced to long prison terms. However, the cases were marked by fabricated evidence, judicial malpractice and political manipulation by the AKP and the Gülenist press, and many were later overturned by constitutional courts.

Given the long history of military coups in Turkey, many among the liberal intelligentsia and the laboring classes alike supported the trials as an end to "military tutelage." But like the anti-Gülen purge today, Erdoğan and his party used the campaign against the military--whatever its merits or lack thereof--as an opportunity to crack down on Kurdish activists, leftists and other oppositionists.

In the wake of these purges of its enemies in the military, the AKP helped place Gülenists within the Turkish Armed Forces. Some of these operatives would later initiate the July 15 coup attempt this year.

IN THE wake of the Great Recession, the AKP began to reformulate its political project. With slowdown in growth, the ruling party turned to interventionist measures to get the economy moving. Property laws were rewritten to enable the state to apply eminent domain over historic city buildings, which were then razed and replaced by new construction.

This was carried out in force in Istanbul, where an initially small protest to defend one of the last green spaces to survive runaway gentrification was the spark that started the 2013 Gezi Park uprising. The AKP also initiated massive infrastructural projects. While the work was carried out by private companies, the government controlled the contracts, and AKP leaders used them to reward their own supporters.

The schism between the AKP and the Gülenists began to emerge over the attempt by the AKP to broker a peace deal with the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK).

The PKK had been locked in a devastating civil war against the Turkish state and its policies of criminalizing the Kurdish identity within an ethnocentric Turkish state. After the 2007 push by the military to destabilize the AKP government, Erdoğan moved toward a peace process to de-escalate the war on the Kurds. This won the AKP further support among a population exhausted by the years of civil war--including a section of the Kurdish population that for a time abandoned traditional parties to vote for the AKP.

But the AKP's overtures to the Kurds were anathema to the military and Turkish nationalism, including the Gülen network, which is ideologically committed to the founding state doctrine of "Turkey for the Turks."

Gülenists leaked word of the government's secret talks with the PKK. In retribution, the AKP cut the Gülenists and TUSKON out of government contracts--a main source of economic stimulus in a time of national and global downturn.

The conflict came to a head several months after the Gezi Park protests of 2013 receded. In December of that year, police, prosecutors and media outlets linked to the Gülen network initiated corruption proceedings against three ministers in Erdoğan's cabinet. The accusations led to renewed anti-government protests that threatened to spread as the Gezi Park movement had.

For the next two-and-a-half years, Erdoğan would lead a campaign against the "parallel state" of the Gülenists within the Turkish government, pushing them out of the police, judiciary and other state bodies. Throughout this whole process--even now during the purges--the AKP has had to contend with the well-known fact that it helped place these now-bitter rivals in their positions of power.

OBVIOUSLY, THE Gezi Park protests in the spring and summer of 2013 were a decisive event in Turkey.

The small group of environmentalists and anti-gentrification protesters who occupied the green space against the threat of another AKP urban renewal project were subjected to a brutal police assault. This time, the spark turned into a blaze--demonstrations spread across Istanbul, and then to other cities around the country, including the heartlands of support for the AKP government.

The Gezi Park movement galvanized people against AKP authoritarianism and neoliberal austerity. In Istanbul, in particular, it brought together young professionals, unions, left organizations, Kurdish activists and Muslim minorities like the Alevis.

Though the nationwide uprising had receded by mid-June, the spirit of Gezi Park continued to have effects in the months and years to come. It drove the protests that emerged later in 2013 against AKP corruption after the Gülenists initiated proceedings. Another consequence was the success of the left-wing People's Democratic Party in elections in 2015.

Drawing its main base from the Kurdish population in eastern Turkey (also referred to as northwestern Kurdistan), the HDP won more widespread support elsewhere in Turkey based on a progressive platform around workers' rights, feminism, LGTBQ issues, and environmental and social justice.

In 2014, one of its co-leaders, Selahattin Demirtaş, ran for president, receiving almost 10% of the vote. But the real breakthrough came in June 2015, when the HDP's bold campaign for Turkey's parliament won 13.1 percent of the vote. This easily surpassed the undemocratic 10 percent threshold for a political party to be represented in parliament--the HDP was awarded 80 seats.

The HDP's electoral success was responsible for overturning the AKP's previously strong parliamentary majority. That posed a challenge to one of Erdoğan's core political objectives--a constitutional revision to increase the powers of the presidency.

The role of president in Turkey has been largely symbolic, but Erdoğan's goal is to amend the constitution in order to consolidate power in the executive branch. When the HDP did so well, the AKP was left without enough members of parliament to push through the changes itself, and it was unable to muster support from the other major parties, the center-left CHP and far-right MHP.

To regain momentum, Erdoğan abandoned the sputtering peace process. The AKP called a new election in the fall, and the campaign of terror and violence begun against the HDP before the June election was escalated. The savage war in Turkish Kurdistan was renewed.

Erdoğan failed in his immediate goal of pushing the HDP's vote below the 10 percent threshold to qualify for parliament, but the AKP did win enough support from the other big parties--thanks to intensified nationalist policies and rhetoric--to regain an outright majority in parliament. After the election, HDP representatives in parliament were stripped of their legal immunity, paving the way for their future arrests.

Since the July 15 coup attempt, the AKP has moved on multiple fronts to consolidate its authoritarian regime.

The purges and mass repression are designed to wipe out both its former allies, the Gülenists, and the leftist opposition party, the HDP. From being seen as a peacemaker, Erdoğan has made clear the government's commitment to crushing Kurdish self-determination, with military assaults on the PKK and outright occupations of Kurdish cities and towns throughout southeast Turkey.

In general, public institutions, businesses and civic organizations are being subjected to strict government control. Working-class people, women and oppressed minorities are bearing the brunt of the onslaught, but the Turkish people in general are living through a tide of anti-democratic repression, carried out by a party that once posed as guardians of democracy against the coup-makers of the military.

Mass mobilizations like the Gezi Park uprising have given people a glimpse of what a different Turkey would look like, based on an expansion of democracy and solidarity. The AKP is proving that it will go to any length to try to prevent this alternative from being realized.